A cry for proper athletic management — is it impossible or couldn’t care less

View(s):

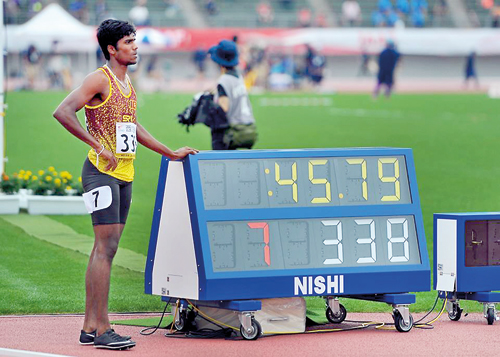

Sri Lanka's latest discovery in sprints - Aruna Darshana

Australia did it differently in the 70s. Poor results at the 1976 Montreal Olympics prompted that Government to see that a sporting overhaul was desperately needed. They embraced sports science and pumped money to become a super power in sports.

It is not that Sri Lanka doesn’t have talent. Of the squad that went to Indonesia this year, at least a dozen athletes have what it takes to be champions. What they lack is a systematic sporting structure that breeds and nurtures them to achieve sporting excellence.

The best example is teenage sprint sensation Aruna Darshana. A few months ago, he clocked a personal best of 45.79 to win gold at the Asian Junior Championships. Since then, he has struggled even to get under 46 secs.

The men’s 4×400 relay quartet came within touching distance of a podium finish and has potential medal winners. Swimmer Matthew Abeysingha, badminton doubles pair Sachin Dias and Bhuwaneka Gunathilaka and several others managed to qualify for the finals of their respective events. But Sri Lankan coaches are just not capable of taking these athletes to the next level.

Sri Lanka is trailing woefully behind, having failed to grasp that the field has shifted from amateur endeavours—such as when Duncan White, Nagalingam Ethirveerasingam and SLB Rosa succeeded—to a highly professional platform where talent is identified early and nurtured scientifically to full potential.

Without a meaningful programme to shift fortunes at international level, Sri Lanka’s fate at the 2018 Asian Games is not surprising. It was predictable.

Incheon in 2014 was disappointing enough but at least we had the cricketers. They won gold and bronze respectively in the men’s and women’s events to place Sri Lanka among the medal winners, softening the disappointment of Guangzhou 2010. Today, there is nothing to write about, not even an odd spark.

A contingent of 177 competitors, the largest ever team to be sent by Sri Lanka, will return home empty-handed next week. This exposes our frail sporting structure that now needs an urgent overhaul if the country is to remain anywhere in the highly competitive world of sports.

This pattern can be traced back to the 2006 Asian Games in Doha, which was the last time Sri Lanka clinched a medal in an Olympic sport with a silver and two bronzes in athletics. Four years later, we didn’t have a single, prompting sports authorities to ruminate over the reasons in a bid to find a solution.

“We do not have proper coaches,” said GLS Perera, a former secretary of the Athletics Association of Sri Lanka who has been involved in track and field since 1975. “As long as we do not invest in sports science, infrastructure and, more importantly, on coach education, we will never become a force to reckon with. This is an initiative that top ranks in Government, including the President and Prime Minister, should get involved in.”

The success of Susanthika Jayasinghe, Damayanthi Darsha, Sugath Thilakaratne and Sriyani Kulawansa was the result of a concerted effort by the Sports Ministry in the early 90s. Targets were set and financial rewards offered for hard work. This worked so well that Sri Lanka became a household name in sprint at Asian Games. Darsha still holds the record for the 200m dash. Together, they have won Sri Lanka five Asian Games gold medals and several other silvers and bronzes.

But the change of Governments and Ministers has left Sri Lanka gasping as successive administrations withdrew support to elite athletes. Had we capitalised on our performances in the 90s, when Sri Lanka even won their first Olympic medal in five decades at Sydney 2000, we would not in the sporting doldrums as we are now.

Both Darsha and Thilakaratne are extremely talented 400m sprinters but their journey was restricted to the Asian circuit because they were reluctant to leave their comfort zones. This was the difference between Susanthika Jayasinghe and others of that era. Most Sri Lankans prefer to dwell in their respective comfort zones.

“Once you identify talent, it’s important that they be exposed best possible coaching under a scientific environment. We do not have such facilities in Sri Lanka. Either we should invest money in getting them or send these potential athletes to countries where facilities available,” he adds.

Sri Lanka must invest in coach education to expose our athletes to high performance training. A country trapped in debt cannot spend lavishly on sports infrastructure development. Funding on this has been minimal, hindering investment on sports science that could maximize player potential with minimal risk of injuries.

For instance, the Government recently suspended its proposed high-altitude training centre in Nuwara Eliya due to the towering financial outlay required. There are just two synthetic tracks for the entire country and one is now dilapidated. There are only three 50m swimming pools, no proper high-tech gymnasiums, no high performance training centres and no qualified coaches to take available talent to the next level.

Sri Lanka does not even have a sports policy. When we hosted the South Asian Games 1991, we beat India in the medals tally in track-and-field. Today, the neighbouring nation is streets ahead, clinching medals regularly at international sporting events while Sri Lanka are fast becoming passengers (just adding to the numbers).

The Asian Games this year were an embarrassment to a sporting nation, even one that is small in population and relatively poor economically. But unless Sri Lanka takes serious note of the shortcoming and spends on infrastructure, science and rewards, our fate will not change.