Sunday Times 2

Is coconut oil poison?

An interesting article titled ‘Apologise, or you’ll send Harvard into disrepute” in the Sunday Times 2 of September 2, prompted me to engage in the issue, when, as Chairman of the Coconut Research Board, having studied the subject in depth in the 1990, I actively fought the myth that coconut oil consumption contributed to heart disease in Sri Lanka!

A Harvard professor, Karin Michels (Prof. KM) is reported to have claimed that ‘coconut is one of the worst foods you can eat’! By contrast, a reputed cardiologist, Dr Aseem Malhotra (Dr AM) makes a scathing remark that Prof. KM’s statement would bring disrepute to Harvard. I cannot agree with Dr AM more knowing how a Harvard group of medical specialists defended coconut oil in the 1980s when the soya oil lobby engaging also the American Heart Association attempted to discredit coconut with the ulterior motive of stopping its marketing and consumption in the U.S.

Soya lobby’s attempt at ‘bombing’ the coconut oil industry!

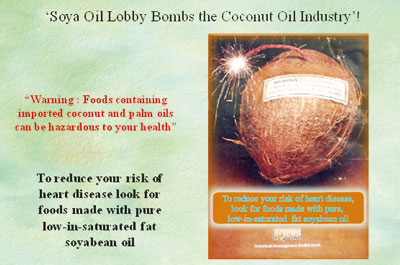

A massive anti-coconut oil campaign launched by the soya lobby in the 1950s caused undue concern globally about coconut oil and health. The picture on this page tells it all.

Before the Second World War, soya oil was hardly used as a dietary fat. It was mostly used in industry such as for making paints! Coconut oil was the most widely used cooking oil in the west. It was then even competing with butter! Disruptions of coconut oil shipments to the west from the east as a result of the Second World War, led to a desperate search of alternatives resulting in a rapid expansion of consumption of other vegetable oils such as soya, corn and cotton seed in the western diet. Some of it was used in the pure form and as margarines. With the resumption of tropical oil (coconut and palm oils) supplies after the war, a massive misinformation and disinformation campaign gained momentum, fuelled by the so-called lipid hypothesis in the 1950s.

The hypothesis is that saturated fats (SFA) in coconut, palm oil and animal fats increase cholesterol and hence the risk of heart disease, whereas polyunsaturated fats (PUFA) in soya and corn oils decrease cholesterol and monounsaturated fats (MUFA)have a neutral or beneficial effect. The matter is not so simple, and is discussed below.

However, cholesterol was blamed as the villain, and coconut and palm oils were labelled “artery clogging tropical oils”. Consequently, over the next two decades, butter (saturated fat) consumption in the US dropped from 18 pounds per capita per year to 10, and margarine filled the gap; and vegetable oil, mostly soya oil and corn oil consumption increased three fold from three pounds to about 10 pounds per capita per year, but heart attack rates did not decline. It was even said that Americans feared saturated fat more than they feared witches! It is now known that trans- fatty acids in margarine elevate cholesterol more than saturated fats.

In 1956, the American Heart Association (AHA) with the lobbying of American Soy Association (ASA) and other vegetable oil interests in the US organised a major fund-raising campaign, concurrently on all three TV channels then in the US, to promote soy and corn oils. Its main agenda was to promote the so-called ‘puritan diet’ – corn and soy oils, margarine, chicken and cereals, replacing coconut oil, butter, lard, beef and eggs. Among the panelists were Ancel Keys, the proponent of the lipid hypothesis, and Paul Dudley White, the cardiologist of President Eisenhower. When pressured to support the prudent diet, Dudley White disputed his ASA colleagues remarking:’ ‘see here (Massachusetts) I began my practice as a cardiologist in 1921, and I never saw a myocardial infraction (MI) until 1928. Back in the MI-free days, before 1920, the fats were butter and lard, and we should all benefit from the kind of fat that we had at the time when no one ever heard of the word corn oil’ Perhaps Dudley White was not quite right. He failed to realise that the advances in medical and health services increased rapidly the life expectancy after the Second World War. In the early 20th century, a high proportion of people died before they reached the heart attack age (50-60 years) from bowel and other diseases.

This is probably why MI was not common then.

The American vegetable oil lobby continued to campaign relentlessly against imported tropical oils, and in 1987 an attempt was even made to label all food containing, coconut, palm and palm kernel oils. A bill entitled”: A bill to amend the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetics Act to require new labels on food containing coconut, palm and palm kernel oil’ was to be introduced. Fortunately, the Philippines Coconut Authority got wind of it and promptly proceeded to hire a team of specialists from the Harvard Medical School, led by George Blackburn, M.D., PhD and it was able to successfully testify against the Bill before the US Senate Committee. In his submissions, Blackburn pointed out that the Americans consumed less than 1% coconut oil in their diet and their heart disease rate was as high as 227 per 100,000 people whereas that of the Philippinos who consumed 6% of the dietary fat from coconut oil was only 22 per 100,000! The bill was withdrawn! So Prof. KM would benefit from digging a bit into Harvard Medical School archives on the matter to get the facts out!

Blackburn also commented that: ‘it would be particularly unfortunate if consumers were deterred from buying products containing coconut oil on health grounds, when most recent medical evidence suggests that coconut oil is more beneficial to consumers than hydrogenated fats (margarines) that would be exempt from the proposed legislation’.

Fatty acids and cholesterol

The composition of the dietary fatty acids in edible oils is highly variable. Those with a high percentage of monounsaturated fatty acids (UFA) such as olive oil, cashew and almonds are considered heart friendly as they do not increase cholesterol. Coconut oil and palm kernel oil are high in saturated fats (SF), there being only small proportions of polyunsaturated (PUFA) and monounsaturated (MUFA) fats. However, in all about 26% of the fatty acids in coconut are not cholesterol elevating.

Coconut oil’s inherent weakness in nutritional terms is the deficiency in essential fatty acids, but a balanced diet of fish or meat, fruits and vegetables should provide them. In a 1989 dietary study in Sri Lanka where a coconut diet was fed to subjects as against a comparable energy diet of corn oil and cow milk, the total cholesterol (TC), high density lipoprotein (HDLC) or good cholesterol, low density lipoprotein (LDLC) or bad cholesterol, rose by 19%, 42% and 24% compared to the control diet.

The substantial increase of HDLC is very beneficial and should be weighed against the increase in LDLC. TC was within allowable limit, but ‘platelet 4 factor’, an index of atherogenicity, increased by 32% in the coconut phase. The concern here, however, is that the coconut diet in the trial had an equivalent of half a coconut per day whereas, the average per capita consumption was only a fourth of a coconut.

According to a further study in Sri Lanka with four populations, two rural, one suburban and the other urban, coconut amounted to 77, 82, 69 and 66 percent respectively of the total fat intake which was 24-25% of the total dietary energy. The lipid profiles were significantly higher in the urban subjects than in the others, but it was within reference values considered non-risky. The urban subjects probably consumed sources of fat other than coconut not done by the other groups. The favourable lipid profiles of the rural subjects observed were considered to be due to greater physical activity.

In similar a study with two Polynesians tribes which derived 35 and56% of the total dietary energy from coconut, the incidence of heart disease was reported to be low. The high fish content in their diet was considered to be the reason. However, when they migrated to Australia or New Zealand their cholesterol levels and heart disease rates shot up, with the concomitant change in diets.

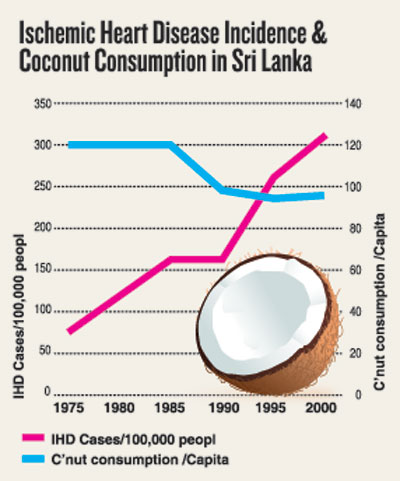

Interestingly, although the coconut consumption had been on the decline over the years, coronary heart disease has sky rocketed in Sri Lanka as seen in the Figure.

In a study in Kerala, India where the coconut consumption is akin to ours, 0.23% of the population suffered from coronary heart disease, in 1979. A sustained campaign on the diet reduced coconut consumption considerably, but by 1993 the heart disease rate had shot up threefold! According to the more recent local coconut consumption statistics, the present consumption is about a third of a coconut per capita per day or about 216 Cals or 9% of the total dietary calorie intake of approximately 2500 Cals. The WHO recommendation is to confine the total fat intake to 30% of the per capita total calorie intake, of which saturated fat should only be a third of it. Accordingly, the coconut intake is permissible given also the fact that not all the coconut fat is cholesterol elevating. However, these coconut consumption figures do not match with those in the second Sri Lankan study quoted above, where it is much higher, but the salutary effect is that, despite this, the lipid profiles of the subjects were satisfactory.

Dietary habits and lifestyles of people have changed over the years. Increased consumption of fast foods and other dietary habits especially among the urban people are a major health concern. These changes may account for the alarming rise in obesity and non-communicable diseases such as high blood pressure, diabetes and heart disease. Given this scenario, it is ridiculous to consider coconut oil consumption as a health hazard!

Health benefits of coconut

There is growing evidence of numerous health benefits of coconut oil. Coconut oil is called a functional food, that is, one that provides health benefits over and above the basic nutrients. The medium chain fatty acids (those with less than twelve carbon atoms in the molecule such as lauric acid) and monoglycerides found primarily in coconut oil and mother’s milk are said to have miraculous healing power. Coconut oil also has anti-microbial properties, and can destroy lipid coated viruses. It is also reported to have anti-carcinogenic effects. Recently there has been a claim from the US of an Alzheimer affected patient recovering from the illness following coconut oil treatment. The demand for coconut oil in the west, as virgin coconut oil, is now more in the flavour and fragrance industries. In fact last year it was declared in some US fragrance products promotion as the fragrance oil of the year! Capsules of coconut oil are now abundant in US and EU supermarkets and consumed for health, especially against alzheimer’s disease.

Cardiovascular diseases are multifactorial and complicated. Despite various controversies relating to the lipid hypothesis, it should, be safe to maintain serum lipid levels below the universally accepted risk limits. Coconut is the second most important source of dietary energy, especially for the poor, after rice and there is no evidence of ill-effects when consumed in moderation. Prof. Karin Michels should have perused the vast literature on the subject of coconut and health before she ‘shot her mouth’.