Columns

Unperturbed Ranil rises above the din

View(s):In the hallowed precincts of a near 200- year old colonial institution Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe gave today’s students of Oxford University a lesson in colonial history and more.

Some of them might not have been aware of the birth and death of the British Empire and what happened in between the beginning and the end. There used to be those pith-hat wearing colonial officials who gloated over their conquests and the growing achievements of the empire. How all this was achieved would not only take too long to tell but would also be to recall some of the darkest hours of British history.

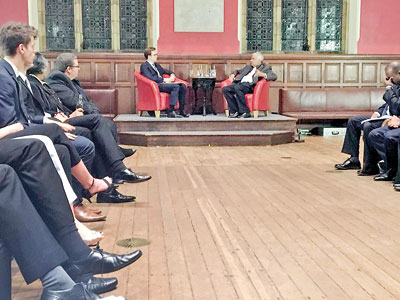

Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe addressing th Oxford Union. Pic courtesy @OxfordUnion

There was a time when British colonialists dispatched to the most distant corners of Asia, Africa and the Americas boasted the sun would never set on their empire only to be told by some subject races that this was because nobody trusted the British in the dark.

As a leader of a one-time British colony and the invitee of a famous institution at Oxford University, Prime Minister Wickremesinghe politely ignored those parts of British history that would have been an embarrassment to today’s undergraduates who are probably lectured to on human rights, the rule of law and democratic norms, while the ex-colonies now sovereign are hectored on how they should conduct themselves on the international stage.

Moreover, though colonialism (more correctly imperialism) is generally on the retreat it is not entirely dead. In fact a 21st century abrasive colonialism is on the march and as long as leaders of major powers such as US President Donald Trump are stomping around the world with inglorious intent, small but proud nations need to tread carefully in their relations with the rich and powerful but without kowtowing to them.

So when British State Minister for Asia and the Pacific Mark Field spends a few days in Sri Lanka lecturing us on civilised conduct and how we must behave on our own patch while they are free to do whatever, not only on their own soil but even on that of others, it behooves us to resurrect events and remind them of their past to restrain them from hectoring others on humanitarian conduct.

This Ranil Wickremesinghe refrained from doing in London last week possibly out of courtesy for his host. But after Mark had a field day in Sri Lanka on his civilising mission a riposte might not have been out of place. Still Wickremesinghe decided to play the civilised gentleman unlike the one-time British Foreign Secretary David Miliband who, on a political visit to Sri Lanka to rescue the LTTE, appropriated the role of a colonial master and tried to bully the then Sri Lankan president Mahinda Rajapaksa only to be taught a lesson he hopefully still remembers.

But Wickremesinghe’s address was more general and in keeping with the conduct of a national leader on a particular mission. It was devoid of the bull-in-a-China-shop approach of a Donald Trump thrashing around in a morass of unpredictability.

Trump can afford to do so as the leader of world’s strongest military power and leading economy and whose finger is not far from the nuclear button. His uncertain behaviour and wayward foreign policy makes Trump an untrustworthy ally and an even worse enemy.

Washington’s firm allies of not too long ago are learning that under Trump’s presidency long standing friends quickly end up as enemies. With the US playing an increasingly assertive role in the Indian Ocean, even New Delhi under Narendra Modi, who was trying to forge a new alliance with Trump, is having second thoughts on its feasibility and reliability.

That is why India is extremely cautious about allowing US warships to call at the Andaman Islands. That is not merely for fear of upsetting China but the uncertainty of relying on Washington under a Trump presidency, particularly if it runs into another term.

That is why India is extremely cautious about allowing US warships to call at the Andaman Islands. That is not merely for fear of upsetting China but the uncertainty of relying on Washington under a Trump presidency, particularly if it runs into another term.

While some Tamil lobbyists conducted megaphone politics some yards from the Oxford Union hall, the din outside hardly perturbed the Sri Lankan PM. His more academic-style speech that made a broad sweep of history from around the 16th century was a reminder that there were great civilisations before the industrial revolution swept Europe to the fore.

“Before 1500 AD, the great centres of world power were outside the Western world. In the Far East, South Asia, the Middle East and the pre-Columbian Central America, there were centres of innovation and creativity, wealth, social organisation, and great economic prosperity. For instance, in the 15th Century, China had an enormous fleet of ships, the greatest fleet in the world. Yet because of the rising affluence of the merchant class, the political elite decided to destroy this fleet and address the more pressing concern of the invading Mongols.”

The reference to China’s maritime power was apposite. For we seem to have come full circle. Today’s concern among regional powers in the Indian Ocean and even nations outside it is directed at China’s expanding blue water navy and Beijing’s moves to stake a permanent place from the eastern Indian Ocean to the African nations bordering the Indian Ocean and beyond.

This presents a major challenge not only to those in the Indian Ocean but also those in the Pacific region as China exerts its power in the South China Sea. With Washington’s chaotic foreign policy even Pacific region nations that came under American hegemony in the post-Second World War era are now trying to slacken their reliance on the US and forge new links to establish more reliable and enduring relationships.

This is the new World Order that Wickremesinghe was trying to convey and why regional states must create a structure to ensure their sovereignty and maritime security for peace in the region.

Sri Lanka, a small littoral state has come under increasing scrutiny and western media attacks since China’s involvement in infrastructure development and financial and military assistance to Sri Lanka to defeat a separatist insurgency that for years had debilitated Sri Lanka and caused irretrievable damage.

The main target of attack has been China’s role in port development especially the Hambantota harbour, which to suspicious western eyes could serve as a Chinese naval base in Beijing’s quest for maritime expansion.

US Vice President Mike Pence, another of Trump’s neocolonial faithfuls but less militaristic than national security point man, the irascible John Bolton, in an important speech recently referred to Sri Lanka as a country that has fallen into China’s “debt trap” and surrendered the Hambantota port to China.

Hambantota port has been so much in focus in western, especially US, geostrategic studies, and commentaries that it was inevitable questions on it would be fired at Prime Minister Wickremesinghe at the Q and A that followed the lecture.

He was quick to dismiss the assertion saying that “some people are seeing imaginary naval bases in Sri Lanka” and insisted there was none.

It was surely appropriate that within a couple of days of his Oxford lecture that focused on the changing world order and the need for peace in the important Indian Ocean region, he was presiding at a regional conference in Colombo on the subject “Indian Ocean: Defining Our Future”.

At that gathering he called for the establishment of a rule-based maritime order in the Indian Ocean before “geopolitical power interplays in the region to convert the Indian Ocean into a centre of tension”.

He said the security and stability of the Indian Ocean could not be left to chance and that states needed to take advantage of the “benign strategic atmosphere that exists, to create a maritime order in the Indian Ocean that can withstand the challenges that may emerge in the future”.

This, he said, could create a more ‘manageable future’. In this context it would not be irrelevant to recall the late 1960s and early 1970s when non-aligned nations were calling for an Indian Ocean free of big power rivalries. It was then that Sri Lanka under Prime Minister Sirima Bandaranaike moved a resolution at the UN General Assembly to declare the Indian Ocean a peace zone free of nuclear weapons.

Sri Lanka’s concern is understandable. Geographically located less than 20 kilometres from its nearest neighbour India, with which it has had a chequered history, growing relations with China, fast emerging as a major military and economic power and building strong ties with Indian Ocean states stretching all the way to Africa and the Gulf and the US casting covetous eyes at the Indian Ocean, small sovereign nations seem caught in a cleft stick.

Moreover the major East-West sea lanes carrying precious cargo and petroleum products to an energy-starved Pacific region pass a few nautical miles from the strategic Hambantota port.

It is these geostrategic concerns that require long-term safety structures to ensure peace and security for small nations that Sri Lanka sees as imperative. But would international laws and regional safeguards be enough when international conduct that smells of a new imperialism with a complete disregard for international norms and laws like the US under the Trump administration begins to act like the gun-toting Mafia of days past.

Leave a Reply

Post Comment