News

Freedom to choose when, who and how they marry

Rifana was 14 years when she was given in marriage; she is 23 now, with three children to provide for following her husband’s desertion, and is battling to obtain maintenance from her spouse through the discriminatory Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act (MMDA).

“It has been one year since he left me, and he has been avoiding court for the past six or seven months,” Rifana told the Sunday Times reporter who met her in Puttalam his week.

“The Quazi court has sent him three letters but there has been no response. The courts are not finding a solution. Instead, they just ask me, if he is not coming to the court how is he going to pay me compensation.”

Instead of enabling speedy relief for her and her children the Quazi court told her the divorce would take at least two years to be finalised.

Rifana makes a living by selling food items to a shop, earning about Rs. 500 a day. “There are days that I fall sick and don’t earn anything that day and we have to go hungry,” she said.

Feroza, a 36-year-old mother of three, said her husband left her and married twice more.

“I was given in marriage when I was 22 years,” Feroza said. “I didn’t know he was in debt. But after I got married I had to sell all I had and give him the money to settle his debts.”

A couple of years into their marriage, her husband left her and Feroza found out he was keeping another family elsewhere.

“I do labour jobs day in and day out to provide for my children. My husband doesn’t even pay maintenance to the children. How can a law allow more than one marriage, especially when it is clearly unfair for helpless women like us?” she asked.

Feroza fears her children could face the same plight if polygamy was allowed to continue.

“I have no trust in the police or the Quazi so I have refrained from going to such places,” she said.

Muslim women seeking justice. Pic by Priyantha Wickramaarachchi

Thirty-year-old Rifaya is another victim of polygamy. “I married my cousin when I was 20,” she said. “After our marriage, he said he wanted money to go abroad and wanted me to pawn all my jewellery. He left the house saying he was going abroad but never sent the money.”

A couple of months later, she found out that her husband had not gone abroad but was, in fact, living with and maintaining another family. Rifaya was made aware that his second marriage had not been registered. “My child refused to go to school because of these problems,” Rifaya said. “She had a mental breakdown and had to be given counselling by her school.”

Children, as well as adults, suffer the tragic consequences of the MMDA. Ten-year-old Salma’s father left her mother two years ago to marry another woman. Her mother was devastated and is now mentally unstable and under medical treatment.

Salma narrates her story in innocence: “I live with my father and his wife but I am not paid much attention. My only friend is my neighbour, who is about 25 years old. Every day he takes me to a forest and does things to me.”

These words from the 10-year-old are agonising to hear. Salma said the man continues his actions despite her protests.

This lonely and neglected child endures trauma because of the archaic Islamic marriage law.

Islam has four schools of thought, known as madhab: the Shafi, Hanafi, Hanbali and Maliki madhabs, with most Sri Lankan Muslims identifying themselves as Shafi and a couple as Hanafi. The Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act (MMDA) differentially applies to both sects.

MMDA was initially introduced to Sri Lanka when the Dutch conquered the island. The law was brought over from Indonesia.

The first reform committee to review the law was appointed in the 1970s, and since then there have been four to five reform committees. The latest was appointed in 2009 by the then Justice Minister, Milinda Moragoda. It is headed by former Supreme Court Judge and Presidential Counsel Justice Saleem Marsoof.

“In Sri Lanka,” Justice Marsoof told the Sunday Times, “the courts have recognised that Muslims in this country belong to the Shafi sect. Section 16 of the MMDA, however, shows that the intention of the legislature was to give opportunities of the laws of madhab to be applied.” That is, that marriage and divorce law follow the customs of each sect, without a common application.

He said the committee’s main concern was to do away with the word “sect” (madhab) and introduce a law common to all Muslims.

Primary recommendations made by Justice Marsoof’s committee include:

- fixing a minimum age of marriage – 18 years for both males and females – and to allow underage marriage to take place, if there is a necessity, only with the permission of the Quazi and only if the girl is aged 16 and over. Marriage below the age of 16 years to be banned.

- curtail child marriage

- allowing women to be appointed as registrars of Muslim marriages and as Quazis

- an option to be granted for any Muslim to be governed by the General Marriage Registration Ordinance (GMRO) instead of the Quazi

- making registration of all marriages compulsory

- preventing the abuse of polygamyremoving the un-Islamic practice of dowry.

Alternate proposals have been put forward by a nine-member committee that includes the All Ceylon Jamiyathul Ulama (ACJU).

Asked about this, Justice Marsoof said: “We agree on most of the crucial matters but there are diverse opinions on certain issues. This kind of diversity is a part of Sharia. It is necessary and has potential for greater development.”

He claimed an attempt by the Ministry of Justice to bring both parties to a meeting failed because some members evaded certain meetings.

Speaking on behalf of the ACJU, Sheikh Fazil Farook said: “There are two proposals, one by Justice Saleem Marsoof and other by Faiz Mustapha. We believe that the report put forward by Mr. Mustapha is more in agreement and conforming to Islamic rulings and teachings than the other.”

The ACJU does not want the word “sect” (madhab) under section 16 of the MMDA to be deleted, Sheikh Farook said. If a problem arose in implementing laws and passing judgments on other schools of thought, people could appeal to the Muslim Marriage and Divorce Advisory Board.

Sheikh Farook said if one set of standards overruled other ideologies and schools of thought this could potentially allow an extremist ideology to take over, or a false school of thought to take control and mislead Muslims.

The ACJU says marriages should be allowed between males above the age of 18 and females over 16 years and that if an underage marriage is mooted the Quazi should make a decision in the best interests of both parties.

“Sharia does not approve of child marriages but underage marriages are not invalidated or illegal as some argue if the Quazi provides a justification regarding the marriage,” Sheikh Farook said.

His committee’s report also recommends against the appointment of women Quazis. “Appointing a woman Quazi is considered reprehensible but they could sit as assessors in a divorce case,” Sheikh Farook said.

This committee also believes Quazis must be given sufficient training in order to provide sound decisions regarding matters and not qualify for the position just because they are “Muslim men”.

“Women have been oppressed and have faced abuse along the way in the manner in which the system was practiced back in the day by the Quazis due to their lack of knowledge regarding the act and improper guidance,” Sheikh Farook said.

He said people “cannot change and exploit the Islamic laws” in the name of reform.

The Justice Ministry said it was trying hard to bring the divided groups to a consensus that was fair to Muslim women.

“The matter has come to a point where it cannot be amicably resolved due to the division but we will have a meeting soon to resolve this issue,” Ministry Secretary W.M.M.R. Adikari told the Sunday Times.

Ms. Adikari said the crucial issue of child marriage would receive close attention as national law made it compulsory for all children to go to school until they are 14 years.

“The current MMDA is addressed separately to each sector in the Muslim community, which creates a lot of problems. All of these people belong to Islam but the difference in interpretation is absurd,” lawyer, reseacher and women’s rights activist Hasanah Cegu Isadeen said.

For instance, she said, a Shafi Muslim female could not sign her own marriage contract while Hanafi and Borah girls could sign marriage contracts. Shafi women could be given in marriage without their consent and even without their knowledge as their marriage only required the signature of a male guardian.

On divorce, there were further discrepancies, Ms. Isadeen pointed out.

A Shafi woman could initiate a divorce on grounds of domestic violence or on any grounds of unfairness. The Hanafi sect, however, did not allow women to file for divorce on grounds of domestic violence. Borah women could not initiate divorce on any grounds.

“There are 64 Quazi courts in the country, with a person from the area appointed as judge. It’s a process that functioned as a means of mediation and didn’t require proper judges but now we have moved far away from that system and society,” Ms. Isadeen said.

“The law in Indonesia has also gone through reforms and has more than a hundred women Quazis, and they still follow the Shafi madhab,” she pointed out.

Ms. Isadeen said that merely appointing women as judges was not going to solve the problem but the right to become a judge should not be denied merely because a candidate was female.

Muslim women want the right to opt out of the MMDA and be able to choose to marry under the general marriage registration law, Ms Isadeen said.

She emphasised it was critical that registration of marriages be compulsory as non-registration would encourage polygamy, which is permitted in Islam, and consequently leave children without birth certificates, as a result of which they would not be able to attend school.

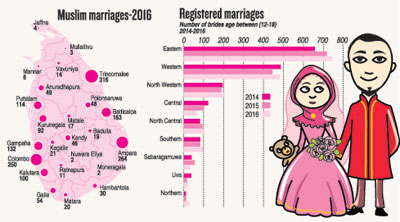

She said child marriages mostly occur in the Eastern Province and in the Colombo, Mannar and Mullaitivu districts, mostly in circumstances of poverty.

She also pointed out that civil law, which is very strict on statutory rape, did not protect Muslim girls in marriage as the MMDA allowed a girl of any age to marry.

“How can something oppressive be right when Islam has said that a marriage should also have the consent of the bride and also says that nobody can be forced into a marriage?” Ms. Isadeen demanded.

“What women are asking for is not something against Islam: it’s their right given to them by their religion which is at present misused and misinterpreted by the men in the community.”

Member of parliament, Mujibur Rahman said he was hopeful that the difference between the two committees would be resolved. He said 90 per cent of the reforms were agreed upon, and most of these “inclined towards the progressive side”.

There were “six or seven issues” on which the two committees differed but he hoped for a solution “very soon” to allow reforms to the MMDA to be introduced in the near future.

| Bride laws in other countries | |

|

| What the current law allows: | |

| Under the current Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act:

|