Amidst fast runners

View(s):Sri Lanka is now among the last group of countries in the region which is growing fast: South Asian countries. Fast growth has shifted from East Asia to South Asia, which has now become the fastest growing region in the world.

Over the past three years, South Asian countries on average have grown by 7 per cent annually, while the average growth rate of developing countries in East Asia and the Pacific has slowed down to 6.5 per cent from their impressive 8 per cent growth during the previous five years.

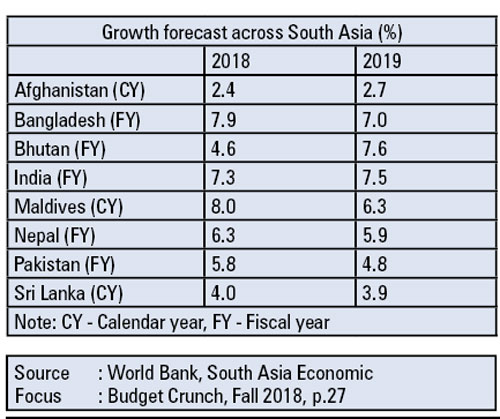

As the World Bank’s latest study on “South Asia Economic Focus” shows, Bangladesh, India and Maldives will grow in 2018-2019 by over 7 per cent per annum. Bhutan and Nepal will grow by over 6 per cent and Pakistan by over 5 per cent. Sri Lanka is set to grow by only 4 per cent or less, while its growth is secondary to Afghanistan only.

I am sure that these growth forecasts are not much encouraging; even by being in the fastest-growing region in the world, if Sri Lanka is set to perform poorly as one of the weakest is not encouraging at all. Should we miss the bus again?

Missing the luxury bus

Sri Lanka missed one of its greatest opportunities in 2009 – in my understanding the “biggest opportunity” in the post-independent history of the country. Someone might ask the question: Whatever that opportunity is, it was in the past; what is the use of a post mortem now?

I have two answers to that question:

The first is that according to my usual reasoning, learning from the past can always enlighten us to minimise the possibility of doing the same mistake in the future. The problem was that, Sri Lanka never learnt and continues to miss the bus all the time.

The second is that it wasn’t a “post mortem” at that time – a real current need of the time which was emphasised in some of the studies. I myself was involved in a study for UNDP in 2009 in assessing the Economic and Social Impact of the Global Financial Crisis in Sri Lanka. The following was a quotation from its concluding section:

“The global financial crisis has brought about an opportunity for the government that cannot be missed out in getting things on right track. The politically-sensitive prolonged policy issues that have resulted in a slower economic growth, weak balance of payments and fiscal mismanagement could be addressed with a bold reform process. Coincidently, this opportunity has been supplemented further by the successful conclusion of the country’s prolonged civil war resulting in a political stability and political strength required for reforms.”

Silver line across the gloomy economy

File picture of harvesting. Rice production has been affected by the vagaries of the weather.

The above quotation does not require an explanation. The year 2009 was marked by a crucial turning point for the Sri Lankan economy at least for two reasons – one is internal and, the other external. Internally, it was the last phase of the 30-year long separatist war. Externally, it was the year that we witnessed the deep bottom of the global financial crisis.

Economic growth slowed down to 3.5 per cent, and the budget deficit rose to almost 10 per cent of GDP. Inflation had been rising and reaching over 20 per cent in 2008.

Balance of payments was in utter disarray, foreign reserves fell to historical lows of just a little more than US$1 billion, but the IMF was late to come with a rescue mission.

In the midst of all above, there was a silver line: A rare opportunity to get things right on track!

Development policies should have been reformed and, the institutions and regulations should have been scrapped and re-established. Budgetary management should have been made efficient and effective making corrections to its historical problems. The public sector including state-owned enterprises would have been restructured, enhancing efficiency. Trade policies should have been reformed accelerating export growth. Business confidence should have been restored boosting private investment.

The required economic and political atmosphere was conducive to undertake all that. But we missed the bus and that opportunity just faded away.

New waves

There are signs of new waves rising up again. The fast growth of South Asia is an indication of the new waves rising up in favour of countries in the region. The increased foreign direct investment (FDI) outflows in the world continued to remain at its heights, around $1.5 trillion a year.

In the midst of a slowdown in China’s growth rate and the possible contract in trade and investment particularly between the US and China, there could be new emerging FDI flows to South Asia. In fact, among developing countries India has already come to be the third in terms of FDI flows around $40 billion a year, and is the 11th among all the countries in the world.

Another dimension of growing Asia is the expanding market for developing countries. Along with higher growth momentum, what comes next would be the market expansion allowing many countries to penetrate into the growing markets. Therefore, in the years to come, developing nations in South Asia will have the opportunity to diversify their markets without confining to the EU and the US.

Growth from domestic consumption

One of the major reservations that the World Bank report on South Asia holds is the source of growth, which might have a self-decelerating impact: “Domestic consumption has been the main contributor to economic growth across the region, with exports or investment being remarkably subdued.”

If growth is contributed more by domestic consumption demand rather than export performance, apparently, that growth momentum is bound to slow down. Although it has been a general observation for the South Asian region, Sri Lanka has already presented an ideal case of this particular problem.

The higher growth momentum that Sri Lanka experienced after 2009 was fueled more by domestic demand from both the government and the private sector than by export growth. And already, Sri Lanka’s growth has slowed down for the same reason.

The story does not end at this point; the country that maintains growth from domestic demand will inevitably encounter the problem of “twin deficits” – the budget deficit and the trade deficit. Sri Lanka got that too.

Fallacy of risk

Opportunities have come again in the form of a higher growth of the region. Unlike in history, we are now in the midst of fast runners; we may feel it even better this time as the fast-changing world is at our doorstep. At least, we should be running along with them.

There is a sense of optimism, but we seem to be worried much more about shallow politics and ins and outs of individuals than our fundamental economic issues. All such talk is directly or indirectly aimed at one thing – forthcoming elections, but not at all knowing anything about what should be done after the elections.

I may not be politically correct. Some might argue that there is a “risk” of doing things. I agree, but there is even greater risk of not doing things. Which government in history has succeeded in not doing things that are supposed to be done?

(The writer is a Professor of Economics at the University of Colombo. He can be reached at sirimal@econ.cmb.ac.lk)