News

Cereal import ban to stay to drive up local output

Last month’s decision to ban cereal imports will not be revoked as it is national policy, the Agricultural Ministry said.

Local farmers will be encouraged to cultivate the crops through the introduction of a floor price and subsidies on seeds and fertiliser, Agriculture Ministry Secretary Ruwan Chanda said.

Two weeks ago, the government moved to ban imports of cowpea, peanuts and black gram from next year. As well. import taxes on green gram and corn are to be doubled in order to encourage domestic cultivation.

In August, a certified price for maize was set in order to assist domestic cultivation. The government will buy maize from farmers at Rs. 43 a kilo. Previously, maize drifted between Rs. 35 and Rs. 40 a kilo, with the price often manipulated by middlemen.

National Food Promotion Board (NFPB) Chairman Buddhika Idamalgoda said demand for maize was increasing due to the flourishing poultry business.

Last year, 180,000 metric tons of maize was harvested during the Maha season but the country had to import another 100,000 metric tons to meet demand.

Next year’s harvest is expected to rise to 50,000 metric tons, Mr. Idalmagoda said.

He said the ministry wants paddy farmers to take up corn cultivation as a rotating crop. “We plan to give out fertiliser and seeds at subsidised rates,” he said.

Although there is very little direct consumption of maize in Sri Lanka it is a staple ingredient in the manufacture of Triposha, which is distributed to pregnant women and to children during their formative years. More than 10,000 tons of maize goes into the production of Triposha every month, Mr. Iddamalgoda said.

The decision to ban cereal imports would certainly encourage local production but comes too late, the Hector Kobbekaduwa Agrarian Research Institute said.

Senior Researcher Duminda Pridharshana said traders had imported stocks well into the next six months of 2019. “This makes the ban futile,” he said.

He suggested a quota system be introduced that would restrict importers from importing excess stock. This would ensure any spillover during the harvesting seasons of the local crop.

“They should import only enough stock to tide over a month,” he said.

Producing crops locally was important because of the cost of imports increasing with the depreciating rupee, he said, warning that global climate change and increasing populations would jack up food prices in the world market.

Today, although Sri Lanka is self-sufficient in cowpea, we import 90 per cent of our peanut and black gram requirement and produce only 40 per cent of potatoes and onions and only a quarter of green gram consumed in the country.

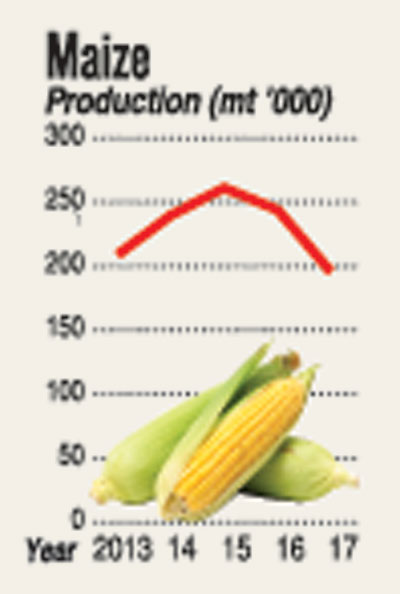

Production of these crops has steadily decreased over the past five years, the Central Bank Report 2017 states, with black gram, cowpea, groundnut, big onions, green gram and maize cultivation sliding from 2013 to 2017 (please see graph).

All-Island Paddy Cultivation Farmers’ Union Organiser, Namal Karunaratne said the decision to stop imports would earn the goodwill of farmers but that successive governments had failed farmers by importing food crops in excess during glut seasons. This pushed farmers into despair, discouraging them from growing the crops on a rotation basis during the Maha season.

“Farmers have to be given incentives including subsidies in terms of fertiliser and seeds and a good water supply,” he said.