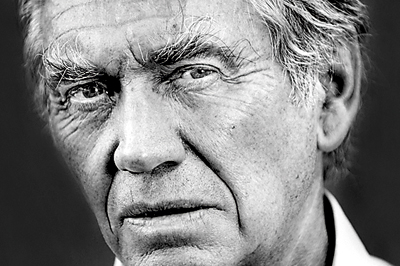

Warscapes to landscapes: Sir Donald McCullin’s haunting images

View(s): The otherwise inexpressible horrors of war explode within his frames and you bathe in the grief and misery, bravery and sacrifice. No one brought the horrors and valour of the frontline to living rooms across the world as did Sir Donald McCullin. Which is why he could easily be Britain’s most renowned photojournalist.

The otherwise inexpressible horrors of war explode within his frames and you bathe in the grief and misery, bravery and sacrifice. No one brought the horrors and valour of the frontline to living rooms across the world as did Sir Donald McCullin. Which is why he could easily be Britain’s most renowned photojournalist.

After his father died of asthma McCullin had to give up his scholarship at a junior art school. But later, when he joined the RAF and worked as a darkroom assistant, his innate visual interest just “came out like a genie from a bottle”.

His first big break wielding the camera: a picture of “The Guvners”- a local gang one of whose members had committed a murder. The photo was bought by the Observer and a door would open out of nowhere for 23-year-old Don, at Fleet Street no less.

A self funded trip to Berlin to see the wall being put up was what made his international reputation, and gave him a taste of being out there amidst strife and conflict, capturing its essence.

The war in Cyprus in 1964 marked the beginning of his career as war photographer. Between 1966 and 1984, he worked for The Sunday Times Magazine, covering Biafra, the Belgian Congo, the Northern Irish ‘Troubles’, Bangladesh, the Lebanese civil war, El Salvador, and the Russian invasion of Afghanistan. He is best known for his iconic photos of Cambodia and Vietnam. He is also a talented essayist and author of more than a dozen books.

He taught himself photojournalism in a country that understood little of the art. He would later call his ‘university’ tomes of journals of sophisticated American work, among them the Photogram photography annuals.

He taught himself photojournalism in a country that understood little of the art. He would later call his ‘university’ tomes of journals of sophisticated American work, among them the Photogram photography annuals.

McCullin believes in the hard way; an artisanal approach. A critic of digital photography, he never air freighted his work, always bringing the film home with him and processing it himself in the darkroom with laborious care.

After he was sacked by the Sunday Times because a new editor thought his work was depressing, Don McCullin started discovering landscapes, giving birth to haunting images where the sky looms large.

When out there he feels the thrill of being “part of the great canvas of history”.

When he feels his body being charged with pleasure in these spaces alive with a sense of the panorama of the past, he denies himself some of that by “remembering how these places were built”. Quoting from the Guardian:

“I know deep in my heart that if there wasn’t that confusion and tension, then I would probably be too happy. And over the years, if I’ve learned anything about myself, it’s that being too happy is the one thing that will never do.”