Nation on a detour

View(s):Sri Lanka now provides a classic case of “how easy it is to drive a nation into a chaos, whoever its architect was”. Although states don’t collapse overnight, the seeds can be sown and nurtured over the years or decades, driving the nation along a destructive path.

I thought of writing today on the relationship between political instability and economic prosperity. There is no need to elaborate the point that it is a timely issue of the Sri Lankan nation. The rift in the relationships between the Executive, the Legislature and, the Judiciary and, the resulting chaos will bring about both short-term and long-term economic consequences to the nation.

The leaders of the nation can also take the nation for a ride, by taking the rift onto the streets and grassroots getting people to get involved in it. Then, thanks to our leaders, the nation and even its future generations will have to pay for it.

Before the drama

If we need to grasp the depth of economic repercussions of the current political instability in Sri Lanka, we should begin with an outline of the economic status prior to the present drama which began with a surprise political change on October 26. The question that we need to ask ourselves is that whether the economy was performing satisfactorily till then?

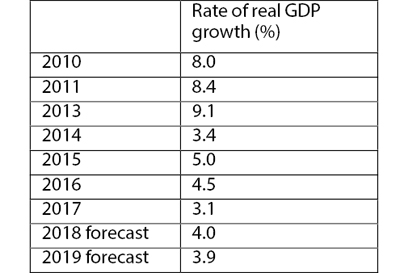

I choose economic growth as the most fundamental requirement of all other development needs of the country. Over the period of the past few years from 2010-2017 the rate of real GDP growth moved to higher levels over 8 per cent initially and continued to decline to around 3 per cent. This wasn’t a surprise as higher growth rates were fueled by “domestic demand” after the end of the war, which was bound to slow down in the absence of two key fundamental requirements of sustainable growth: export growth and investment growth.

Although South Asia has now become the fastest-growing region in the world, Sri Lanka is not yet there. The country has been moving away from being part of growing South Asia with its sluggish performance. According to the available economic forecasting, the rate of real GDP growth for 2018 and 2019 would not show a breakthrough.

Slowing down growth

Why was Sri Lanka unable to sustain its higher growth momentum? This is because there was no significant increase in private investment particularly in the areas that are designated as “tradable” sectors.

The higher levels of growth in some years – 2010, 2011 and, 2012, was due to increased government spending, construction and reconstruction and, some other sectors which responded immediately to the peace in the absence of the war. These sectors are basically termed as “non-tradable” sectors.

The problem of growth emanating from above sectors cannot sustain itself in the absence of growth through “tradable” sector. It was obviously bound to slow down. And this slowdown is also accompanied by rising budget deficits and debt burden. Which we are familiar with today.

Rowdy scenes in Parliament on Thursday.

Sluggish export growth

There was no significant increase in private investment in the “tradable” sector which produces goods and services for the export markets. This is further confirmed by the sluggish performance in export growth.

It is the tradable sector that has the ability for self-sustaining growth. Besides, tradable sector growth is necessary to sustain growth from “non-tradable” sector as well.

Export expansion was sluggish because it should come from long-term private investment. Private investors showed much enthusiasm for investing in Sri Lanka since the end of the war, but that initial investment spurt quickly faded away.

Since then, they became cautious about the deterioration of the business environment. They continued to act on “wait and see” attitude towards investing in Sri Lanka.

New drama

It was the backdrop of the new drama which unfolded suddenly, confirming the “wait and see” attitude of private investors. In the current set up with political instability, how do we anticipate the economy to respond? Do we expect a change in private investors’ attitude?

There is no shortage of economic research on the deep interconnection between political instability and economic growth. They all confirm two basic points:

- Political instability has been a major underlying factor of poor growth performance in many developing countries, compared to the higher growth performance in countries that are politically stable.

- A much deeper issue is that poor economic performance itself leads to much larger political instability, including political unrest and insurgencies, creating spiral effects of one reinforcing the other.

Multiple issues

Even if our political leaders, acting wisely enough to settle the current issue of political instability, the echo that it has already created will have a much larger impact on the mediumterm economic performance of the country. The mediumterm slowdown in growth performance leads to a multiplication of the issues with which the country has already faced .

Poor growth performance will aggravate the government’s budgetary management issue. This is because along with poor economic growth, the government’s tax revenue generation will slow down but expenditure will begin to rise faster. Some of the politically-motivated expenditure decisions may exacerbate the problem of government finance. Poor economic performance will drag on the sluggish export growth as well exerting further pressure on the long-term exchange rate.

It is not necessary to elaborate that on both accounts, Sri Lanka has already experienced both budget deficits and trade deficits – the “twin deficit” problem. The only way for the economy to escape the twin deficit is through higher economic growth.

Historical lessons

Sri Lanka does not have a shortage of lessons from our own history. The poor economic performance against growing aspirations of “educated youth” has been in the heart of the country’s civil wars – in the North among Tamil youth as well as in the South among Sinhalese youth.

Although wars in the North and South both were over, the frustration of the “educated youth” has not yet abated in the face of sluggish growth performance. As Prof. Rev. W. Wimalaratana, an economist, once elaborated on the issue, “educated youth may not engage in collective violence again in the near future, instead they are now leaving the country as individuals.”

Brain drain in the midst of sluggish economic performance is already grown into an aggravated problem. It’s most dangerous negative implications are related to the fact that there will not be skilled labour even when the country is ready for a take-off in the future.

The end

The end of the current political chaos might come into effect with preparation for a Parliamentary election. Or a more admirable move could be that someone might decide to step back for the sake of the nation. Whatever it might be, it may not be the end for the economy. Whether it is going to be the end or the beginning of another cycle of poor economic progress for the country depends on how soon we end our detour and bring the economy on the road to prosperity.

Then we might be able to forgive and forget politicians taking the nation for a ride by denying the economic prosperity of the nation.

(The writer is a Professor of Economics at the University of Colombo. He can be reached at sirimal@econ.cmb.ac.lk)