News

Angry Sirisena breaks foundations of the pillars of democracy

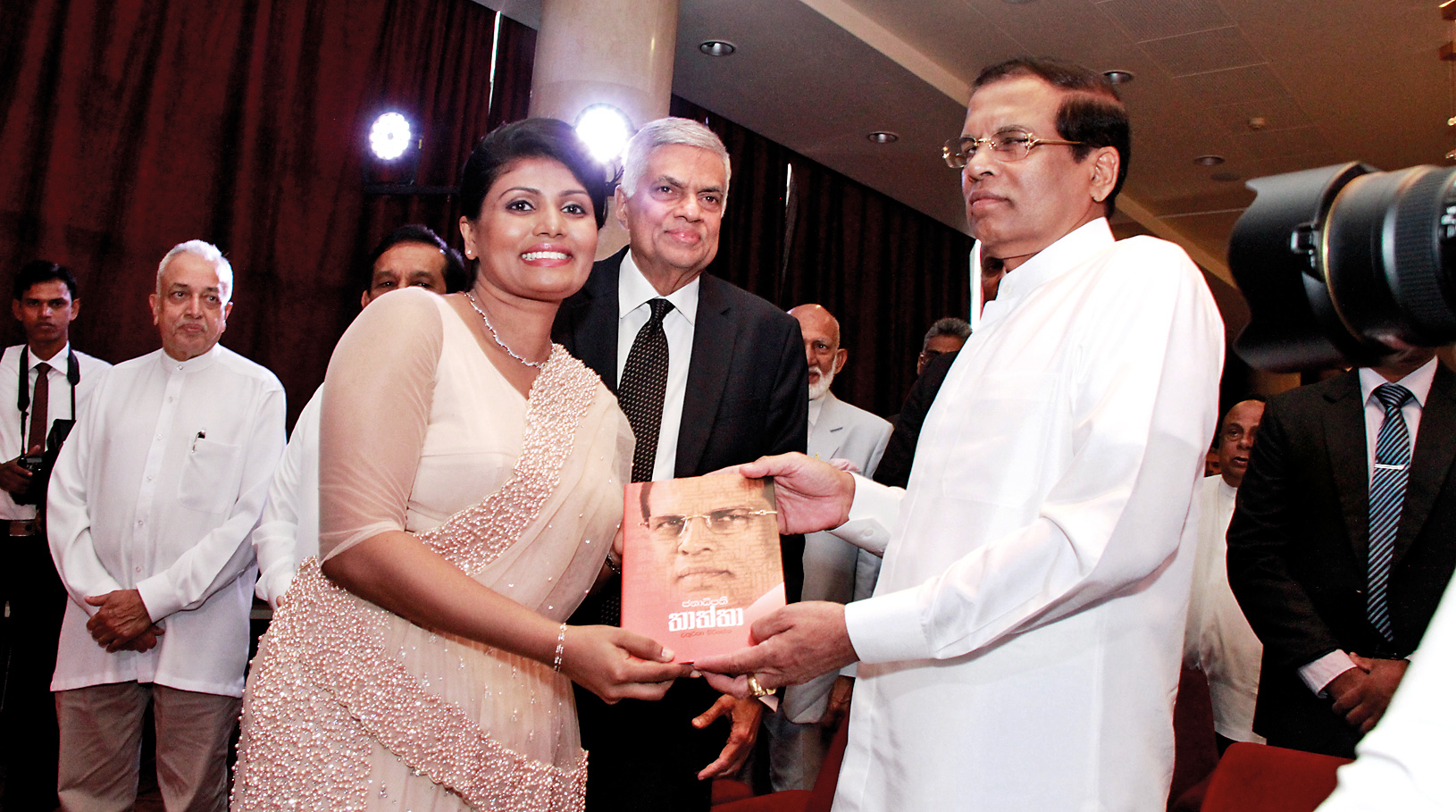

View(s):In an extract that is circulating in social media, Chathurika Sirisena, daughter of President Maithripala Sirisena describes her father in her book Janaadhipathi Thaaththa (‘Presidential Father’) as a very innocent man who however doesn’t know what he is doing when he is angry. The younger Sirisena recalls an incident in Maithripala Sirisena’s childhood where he was admonished by his own father with a knock on his head (‘tokka’). In retaliation,Sirisena reportedly set fire to a lush paddy-field!

These days, Sirisena certainly appears to be an angry man, setting alight the country’s pillars of government. A fortnight after he summarily dismissed Ranil Wickremesinghe through a Friday night gazette notification, he issued another Friday night gazette on November 9, announcing the dissolution of Parliament and calling fresh elections. Many questioned as to whether he knew what he was doing.

That is because the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, introduced by his government with Sirisena himself working overtime and being personally present in Parliament to see it through, specifically precludes him from doing so.

Following the adoption of this amendment, Article 70(1) of the Constitution now reads: “The President may by proclamation, summon, prorogue and dissolve Parliament, provided that the President shall not dissolve Parliament until the expiration of a period of not less than four years and six months from the date appointed for its first meeting, unless Parliament requests the President to do so by a resolution passed by not less than two-thirds of the whole number of Members (including those not present), voting in its favour”.

The wording seems unambiguous. However, Sirisena- perhaps acting on legal advice- chose to act on another provision of the Constitution, Article 33(2)(c), which states that; “In addition to the powers, duties and functions expressly conferred or imposed on, or assigned to the President by the Constitution or other written law, the President shall have the power to summon, prorogue and dissolve Parliament”.

Sirisena and his advisors contend that the words ‘in addition to’ imply that Article 33(2) can be read as a stand-alone provision, in isolation from Article 70(1). This would suggest that the President can dissolve Parliament at his whim and fancy, at any time when, even prior to the introduction of the 19th Amendment, there was a one-year time period during which the President was barred from doing so.

Sirisena’s latest move was one of a three-pronged strike on the legislature within a fortnight. The dismissal of Wickremesinghe and the appointment of Mahinda Rajapaksa in his stead was followed by the prorogation of Parliament (an action he was entitled to, although he defied tradition by not consulting or informing the Speaker), culminating in the controversial dissolution of the House.

Friday's day of shame in Parliament. Pixby M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Sirisena has addressed the nation, explaining the reasons for his actions and citing irreconcilable differences with Wickremesinghe, in an attempt to justify his actions. Later he told a mass rally in support of the new Prime Minister that he had offered the post to Speaker Karu Jayasuriya and UNP deputy leader Sajith Premadasa, which put Mahinda Rajapaksa in a bad light as if he was only an after-thought. But it also showed, that Sirisena first tried to split the UNP down the middle by offering the post to two senior UNPers.

Sirisena’s recent actions are better understood in the context of his own political predicament. He leads a Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) group of the United Peoples’ Freedom Alliance (UPFA) which is growing smaller by the day and commands the loyalty of only about two dozen MPs. It suffered a drubbing at the hands of the newly formed Sri Lanka PodujanaPeramuna (SLPP) led by Rajapaksa at the local government elections. So, Sirisena has to forge a pathway for his own political survival beyond 2020 despite promising repeatedly during his presidential election campaign and even after his election that he would be a one term President.

Having already alienated the UNP with his vitriolic public comments and knowing that he wouldn’t stand a chance if he ran on his own steam against a Rajapaksa fielded by the SLPP, Sirisena has chosen the alternative option: cosying up to the Rajapaksas again, offering the Premiership to Mahinda Rajapaksa and the prospect of being in government for his loyalists, while calling for a general election which, it was calculated based on the results of the local government polls and the lacklustre performance of the UNP in office, the SLPP-SLFP combine would win.

That would set the stage for MahindaRajapaksa to be Prime Minister, Sirisena would remain as President until the next presidential poll where Sirisena hoped he would be endorsed as the ‘common candidate’ once again, albeit from the SLFP and the SLPP this time around- although it is unlikely Sirisena had any guarantees from the Rajapaksa camp about his candidacy. Still, he would have an exit route with the Rajapaksas in power and place without being hounded out for the ‘treacherous act’ of decamping in late 2014 and defeating Rajapaksa.

Sirisena and his ‘dealmakers’ led by the unscrupulous but equally garrulous S. B. Dissanayake, with Basil Rajapaksa handling the Rajapaksa faction, believed that if Wickremesinghe’s dismissal is made a fait accompli by Presidential fiat, UNP MPs would flock to Sirisena who could reward them with portfolios. The prorogation of Parliament would allow a timeframe for the dealmakers to swing into action and swell their ranks. This they did and about five UNPers did cross over but in the parliamentary numbers game, that was not enough. It was a fatal miscalculation.

Father and daughter at the launch of Janaadhipathi Thaaththa; the book that reveals a telling incident of a temper tantrum by the young Sirisena

Had Rajapaksa been able to demonstrate majority support in Parliament, the on-going political tussle would have ended for all practical purposes. Wickremesinghe and the UNP would have still complained of being dismissed unconstitutionally but that then would have been only a moot point: an academic issue for students of politics to debate about in the years to come. Instead, the best laid plans of Maithripala Sirisena and Mahinda Rajapaksa have now gone awry.

It is not that Sirisena- and indeed Rajapaksa- were not forewarned. Their joint putsch to oust Wickremesinghe through a vote of no confidence in April this year failed for the same reason: not enough UNPers were willing to take the plunge against their leader. Having had that experience, Sirisena should have ensured that he was doubly sure of his numbers. Making an error once is pardonable; making the same mistake again smacks of political naivete, unbecoming of a President, or a former President, for that matter.

Annoyed and angry at this turn of events, Sirisena turned arrogant. Pushed into a tight political corner and ill-advised about the legal nuances of his decisions, Sirisena has attempted to cover up one bad decision with another, leaving a snowballing trail of political instability: the dismissal of Wickremesinghe was followed by the prorogation of Parliament which in turn was followed by its dissolution, which is now being challenged in court.

Rajapaksa’s judgement in this saga also needs to be called into question. Had he patiently waited in the wings, the government would have been his for the taking in 2020 because of the UNP’s lack of empathy for the economic woes of the masses and it’s not so squeaky-clean record while in government. Instead, he chose to act like an old man in a hurry, perhaps concerned about the many prosecutions progressing against him and his family members.

As a result, Rajapaksa now faces the real prospect of being rejected by Parliament, an ignominy that a war-winning charismatic leader does not deserve in the evening of his political life. He, along with Sirisena have been the butt-end of satire on social media. Even more worryingly, the behaviour of his loyalists after returning to government- the takeover of state media and other institutions with lightning speed, mobs attacking several ministers at Rupavahini and Arjuna Ranatunga at the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation and the thuggery witnessed in Parliament – have reminded the masses of the darker side of the Rajapaksa era. The shocking appointment of someone under scrutiny by a Presidential Commission of Inquiry as Chairman of the national airline, only to be reversed within 24 hours when there was a public outcry was a pointer to the questionable Old Guard making a comeback.

The determination of the Rajapaksa faction to cling onto power by clutching at straws in constitutional clauses has not endeared them to the people either. Inadvertently, this may have even thrown a lifeline to the ailing UNP which now has issues- the abuse of power and the impunity towards the rule of law- which it can canvass before the electorate, arguing that the Rajapaksa they dethroned and his cohorts have not changed their mean ways.

Back then: Maithripala Sirisena being sworn in as President

Sirisena, by inviting Rajapaksa to take over the reins, has also unleashed another monster. Earlier this week, dozens of SLFP parliamentarians rushed to obtain membership of the SLPP, Rajapaksa’s new political outfit with the ‘pohottuwa’ (flower bud) symbol. That is an indication that, if there ever is a tussle for leadership of the SLFP-SLPP combine, Rajapaksa will always be the winner. Sirisena can insist on his pound of flesh- the candidacy for the 2020 presidential elections- but he may never get what he wishes for.

He could also be accused of betraying the promises he made as a presidential candidate but he wouldn’t be the first to do so. J. R. Jayewardene, while blaming Sirima Bandaranaike for not conducting a general election in 1975, refused a general election in 1982 when he was President, Chandrika Kumaratunga promised to abolish the Executive Presidency and so did Mahinda Rajapaksa. After all, politics, as Otto Von Bismark said, was the ‘art of the possible’.

For Sirisena however, the last few weeks have been spent trying to perfect the art of the impossible, stretching constitutional interpretations to their limit, confounding legal pundits and creating a constitutional crisis, the likes of which this country has not seen before. As a lawyer pointed out during Monday’s Supreme Court proceedings, “the President should not behave like Alice in Wonderland”- or indeed, a bull in a China shop.

Sirisena’s precipitous actions have created a nation in limbo with two Prime Ministers, a Parliament that is awaiting its fate from the Supreme Court and a government and Cabinet of Ministers that have lost a vote of no-confidence in Parliament. It is constitutional chaos at its worst and will take its toll on the economy and hurt Sri Lanka’s image as a vibrant and robust democracy for years to come. Sirisena’s reputation as a democrat has been sullied forever and his credibility is in tatters.

Had Maithripala Sirisena kept his promises, his footnote in history would have acknowledged him as the man who steered the country away from an oligarchy where democracy and the rule of the law were dying a slow death. Unfortunately, he will now forever be remembered as the leader who didn’t think twice about plunging the nation into anarchy, just so he could remain in power for a few years more.

Sadder still is the fact that Maithripala Sirisena elected on January 8, 2015 was a decent man and a democrat. In little less than four years, by October 26, 2018, the same Maithripala Sirisena has metamorphosed into virtual dictator and despot amply demonstrating that it is but a short step from the sublime to the ridiculous. Such are the powers of the Executive Presidency!