News

With prolonged grief, the families of the missing cry out for help

Limbo – this is the tragic state in which many family members of the missing are living, with no hopes and aspirations for the future, only despair and heart-rending sadness.

The 2004 tsunami : A tragedy that left many “unaccounted for”

For the first time in Sri Lanka and the world, two Psychiatrists have taken the time off their busy schedules to sit down and talk to the families of the missing or disappeared in their own homes in the south.

“Many broke down and wept even so many years later,” say the researchers, adding that a mother of a bright boy who had got eight distinctions at the Ordinary Level but disappeared during the 1988-89 insurrection, kept her front door open every single night in expectation of her son’s return.

She had done this until her own death.

As recently as a week ago, a family member of another missing person had asked the researchers whether she would be able to move on, at least in the New Year.

The findings of this four-year research which has been carried out in a systematic and ethical manner are a disturbing eye-opener, crying out for action not only on the part of their relatives and friends and the community but vesting severe responsibility on the authorities to act now and not tomorrow.

The study has been conducted by Prof. Shehan Williams, Professor in Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Kelaniya and Dr. Amila Isuru earlier of the University Psychiatry Unit of the North Colombo Teaching Hospital, Ragama and now Acting Consultant Psychiatrist of the Mannar Hospital.

The findings under the title ‘Unconfirmed death as a predictor of psychological morbidity in family members of disappeared persons’ have been published in the prestigious high-impact ‘Psychological Medicine’ journal of the Cambridge University Press at the end of December (last month).

This too is believed to be a first for Sri Lankan researchers.

Coincidentally, the Office on Missing Persons (OMP) announced on Monday that as it completes its first year in February, it has launched a communications campaign titled ‘Pain never disappears, let’s fulfil our responsibility to find the truth’ to bring attention to the plight of the families of the missing and disappeared.

“The campaign aims to generate awareness and empathy towards the suffering of Sri Lankans who are still waiting to learn the truth about the fate of their loved ones. The campaign will include video and audio content highlighting the diverse impacts on the families of the missing, who share a similar pain,” the OMP said.

Prof. Shehan Williams

Dr. Amila Isuru

The Sunday Times hears a resonance from the researchers as they reiterate that for true reconciliation in the country, the families of the disappeared or missing cannot be left behind.

The daily routine of these families is to wake up every morning and go in search of their missing loved one. Distances they would travel even if there was an iota of information about their loved one, while frequenting numerous soothsayers, says Prof. Williams, saddened because society as a whole does not acknowledge their suffering.

They keep walking to the door to see whether their loved one is returning and sighing over and over again: “I wish he/she were here.”

Theirs is a tangible grief, the weeping is not over yet, says Dr. Amila recalling how they would open up “crying a lot” after about an hour of talking.

“They need to find closure and it is the duty of all of us, the community and the authorities to help and support them,” says Prof. Williams, with strong echoes from Dr. Amila.

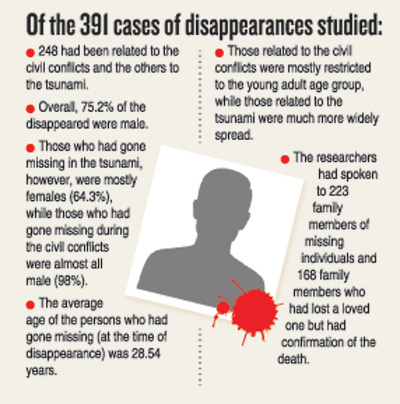

Before their poignant meetings with the families of the missing and disappeared in Matara, Galle and Hambantota involving 391 cases of disappearances, they had looked at all literature on the missing, both nationally and internationally.

With Sri Lanka having frequent disappearances over a prolonged period of time, the researchers picked the 1988-89 youth insurrection, the December 2004 tsunami and the three-decade war which have left a large number of people “unaccounted for”.

The Presidential Commission on Missing Persons in Sri Lanka has received more than 20,000 complaints including more than 5,000 missing from government forces, say the researchers, quoting the ICRC.

Many families of the missing never found the body of their loved one – whether it was a youth who was abducted in the late 1980s, a person who was caught by the huge waves that hit the coast in 2004 or a soldier missing-in-action in the war.

Even 20 years down the line, these families remain stuck in one place, although the world has moved on. They have no closure, says Prof. Williams, while Dr. Amila reiterates that they are “holding onto hope” of their loved one returning.

Hope is what they cling to and nothing in their lives has been sorted out, whether it is property and houses in the name of the missing person or monies.

When they asked the families whether they believed that their loved one was alive, two-third of them had answered in the affirmative, assuming that they were being held in a psychiatric institution, they had escaped abroad or been abducted.

Accepting the death of their loved one was a problem as there has been no body (mortal remains), no funeral rituals and no mourning period.

Both researchers stress that these families have not mourned, they have not buried or cremated their loved one and they have not had the privilege of indulging in the role of rituals. The grieving is prolonged.

Now the authorities issue a ‘missing’ certificate but the families are reluctant to accept it, believing that if they do, they would be letting down their loved one who may be alive somewhere. That it would be an act of treachery and disloyalty.

Looking at the role of the wife/widow, Dr. Amila says that these are families with the father physically absent. The mother is psychologically down, which leads to the children being neglected.

What is the role expected of her by society, asks Prof. Williams. Should she await her husband’s return? Should she think of him as dead and mourn for him? Or should she move on?

Their heartfelt plea is: The world has gone by, but there are some still stuck in the past amongst us and we need to address this soon, as a society and nation.

| The pathetic tale told by the numbers | |

| The aim of the study which covered 391 cases of disappearances in the Southern Province was to check out the prevalence of Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) in families of disappeared individuals. It also compared and contrasted those who eventually received the mortal remains and those who did not. This was while the study looked at their belief as to whether the missing person was still alive or dead. (See graphic) All these families were identified through the District Secretariat and the Grama Niladharis. Some families, however, had not volunteered to divulge information due to “understandable” reasons such as security issues and stigma. If the interviewee had lost more than one family member, he/she had been asked to specify whose death was most difficult to cope with and to base their answers with reference to that person. When taking the families of the missing:

|

| They have psychological issues | |

| The assessment of the mental health of the families of the missing:

| |

| The way for Sri Lanka as a people and nation | |

| Prof. Shehan Williams and Dr. Amila Isuru show the way how to support the families of the missing and disappeared. At an individual level, they have to be helped to overcome the psychological impact through therapy by getting them to believe or be convinced that the person is no more, they say, pointing out that this has to be reinforced at community and national levels. Such families also need to be shown that the authorities have done everything possible to find the missing persons and render adequate compensation as most of them are facing financial hardship, says Prof. Williams. Dr. Amila adds that they need to feel that they are not “unique”, they are not alone but that there are many others in a similar situation. They need to be provided a platform to share their problems and sorrows. These are a few ways that they can deal with their “ambiguous loss” and get on with their lives which they have put on hold. Both Psychiatrists point out that the disappearance of a family member leads to uncertainty and inhibits the normal grieving process that occurs following the death of a person. The families need to be supported by psychological services to prevent, identify early and treat the associated psychological morbidity. The government and greater civil society need to enable mechanisms that facilitate closure for these families. |