A letter to you from

View(s):The mind wanders and lurks in the most ungodly and deadliest of spaces.

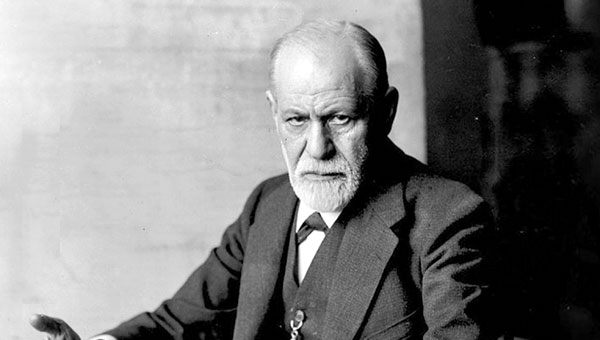

I was born in Freiberg, Moravia in 1856. I was the oldest of eight children.

Our family moved to Vienna when I was four years old. I studied at a preparatory school in Leopoldstadt where I excelled in Greek, Latin, history, math, and science. I was able to gain entrance into the University of Vienna at the age of seventeen. Upon the completion of which I went on to pursue my medical degree and PhD in neurology.

Our family moved to Vienna when I was four years old. I studied at a preparatory school in Leopoldstadt where I excelled in Greek, Latin, history, math, and science. I was able to gain entrance into the University of Vienna at the age of seventeen. Upon the completion of which I went on to pursue my medical degree and PhD in neurology.

I was intrigued by the theories on brain function that were emerging during the late 19th century and opted to specialize in neurology. Many neurologists of that era sought to find an anatomical cause for mental illness within the brain. I also sought that proof in my research, which involved the dissection and study of brains. I was enthusiastic and had a thirst for knowledge that I became knowledgeable enough to give lectures on brain anatomy to other physicians.

I eventually found a position at a private children’s hospital in Vienna. In addition to studying childhood diseases, I developed a special interest in patients with mental and emotional disorders.

It was disturbing to see that the methods used by professionals to treat mental indifferences. Long-term incarceration, hydrotherapy (spraying patients with a hose), and the dangerous (and poorly-understood) application of electric shock were few of what they then thought was best. But wasn’t it inhumane? It was more torture than curing patients!

One of my early experiments did little to help my professional reputation. In 1884, I published a paper detailing an experimentation with cocaine as a remedy for mental and physical ailments. I sang the praises of the drug, which I then administered as a cure for headaches and anxiety. It didn’t turn to the best because humans being humans, managed to use it for the worst. I had the cocaine study shelved after numerous cases of addiction were reported by those using the drug medicinally.

In 1885, I traveled to Paris, having received a grant to study with pioneering neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot. The French physician had then recently resurrected the use of hypnosis, made popular a century earlier by Dr. Franz Mesmer.

Charcot specialized in the treatment of patients with “hysteria,” the catch-all name for an ailment with various symptoms, ranging from depression to seizures and paralysis, which mainly affected women.

Charcot believed that most cases of hysteria originated in the patient’s mind and should be treated as such. He held public demonstrations, during which he would hypnotize patients (placing them into a trance) and induce their symptoms, one at a time, then remove them by suggestion.

Although some observers (especially those in the medical community) viewed it with suspicion, hypnosis did seem to work on some patients.

I was greatly influenced by Charcot’s method, which illustrated the powerful role that words could play in the treatment of mental illness. It is during this time that I came to adopt the belief that some physical ailments might originate in the mind, rather than in the body alone.

Returning to Vienna in February 1886, I opened a private practice as a specialist in the treatment of “nervous diseases.”

As my practice grew, I finally earned enough money to marry Martha Bernays in September 1886. Martha was my sweetheart which is an entirely different part of my life. We moved into an apartment in a middle-class neighborhood in the heart of Vienna. Our first child, Mathilde, was born in 1887, followed by three sons and two daughters over the next eight years.

I began to receive referrals from other physicians to treat their most challenging patients — “hysterics” who did not improve with treatment. I used hypnosis with these patients and encouraged them to talk about past events in their lives.

I dutifully wrote down all that I could learned from them — traumatic memories, as well as their dreams and fantasies.

One of the most important mentors during this time for me, was Viennese physician Josef Breuer. Through Breuer, I learnt about a patient whose case showed me, more to everything I have ever developed.

“Anna O” (real name Bertha Pappenheim) was the pseudonym of one of Breuer’s hysteria patients who had proved especially difficult to treat. She suffered from numerous physical complaints, including arm paralysis, dizziness, and temporary deafness.

Breuer had treated Anna by using what the patient herself called “the talking cure.” She and Breuer were able to trace a particular symptom back to an actual event in her life that might have triggered it.

In talking about the experience, Anna found that she felt a sense of relief, leading to a diminishment — or even the disappearance of — a symptom. Thus, Anna O became the first patient to have undergone “psychoanalysis.”

The case of Anna O, was intriguing and inspiring to me, I then incorporated the talking cure into my own practice. Before long, I did away with the hypnosis aspect, focusing instead upon listening to my patients and asking them questions.

Later, I asked fewer questions, allowing the patients to talk about whatever came to mind, a method known as free association. As always, I kept meticulous notes on everything the patients said, it was a case study to me and indeed it was scientific data.

As I gained experience as a psychoanalyst, I developed a concept of the human mind as an iceberg, noting that a major portion of the mind — the part that lacked awareness — existed under the surface of the water. This is known as the “unconscious.”

Other early psychologists of the day held a similar belief, but I was the first to attempt to systematically study the unconscious in a scientific way.

I developed the theory — that humans are not aware of all of their own thoughts, and might often act upon unconscious motives – this was considered a radical one in its time. As it is and always will be these ideas were not well-received by other physicians because I could not unequivocally prove them.

In an effort to explain my theories, I co-authored Studies in Hysteria with Breuer in 1895. The book did not sell well, but nothing could stop me from doing what I loved doing. I was certain that I had uncovered a great secret about the human mind.

If you are aware, people now commonly use the term “Freudian slip” to refer to a verbal mistake that potentially reveals an unconscious thought or belief. Funny as it is, but back then it was a task to prove what I knew was true.

After my 80 year old father died, I analyzed myself. I would psychoanalyze himself, setting aside a portion of each day to examine my own memories and dreams, beginning with my early childhood.

During these sessions, I developed his theory of the Oedipal complex (named for the Greek tragedy), in which I proposed that all young boys are attracted to their mothers and view their fathers as rivals. These were all very controversial and not many agreed to these notions.

I could go on and on about my life’s findings. My collaboration with Carl Jung, interpreting dreams and about Id, Ego, and Superego. I later found out that the mind comprised of three parts; the Id (the unconscious, impulsive portion that deals with urges and instinct), the Ego (the practical and rational decision-maker), and the Superego (an internal voice that determined right from wrong, a conscience of sorts).

I got carried away with telling you how important mental health is important, because now more than ever people are affected with mental illnesses rather than physical plagues.

Unexpressed emotions will never die. They are buried alive and will come forth later in uglier ways. Consider your mind to be capable of far greater things which you never would imagine possible. Don’t cage the lion by suppressing what need not be.

Out of your vulnerabilities will come your strength,

Sigmund Freud.

Written by Devuni Goonewardene (email any feedback to devuni@gmail.com)