Bangkok’s Phra Buddha Sihing and the Sri Lankan connection

Phra Buddha Sihing: The statue that continues to inspire Buddists around the world. Pic by Sujiva Dewaraja

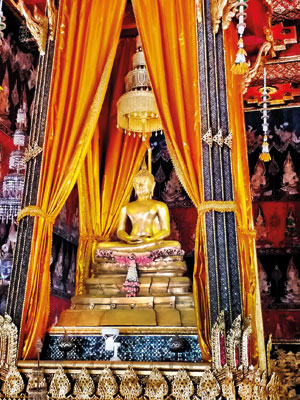

The “Phra Buddha Sihing” bronze and gold Buddha statue which commands pride of place at the Buddhaisawan Chapel right at the front of the National Museum, Bangkok is considered the second most revered Buddha image in Thailand after the “Emerald Buddha”.

The aura of this image is dignified, quietly refined and serene. The face is round with the faintest trace of a smile and the Ushnisha (protrusion from the head) almost merges with the pointed curls of hair. Elongated fingers of equal length make delicately sinuous curves. The image is surrounded in the chapel interior by the magnificent murals depicting the life of the Buddha atop which are rows of celestial beings, all of whom gaze reverentially at the spot where the Sihing sits close to the centre of the floor.

The chapel was purpose-built in 1795 to house the Sihing as a private chapel for the Maha Uparaja or deputy prince, a younger brother of King Rama I. The image, believed to be spiritually protective and a symbol of Royal authority has been seized and re-located multiple times from Nakhon Si Thammarat to Sukhothai to Chiang Mai (Wat Phra Singh) to Ayuthaya. It was again removed from the Buddhaisawan Chapel upon the death of its architect, the Maha Uparaja for safekeeping to the Grand Palace and was not returned to the chapel until the reign of King Rama IV in the mid 19th Century. Every Songkran (Thailand’s New Year), the statue is taken out and placed for public veneration at the “Sanam Luang” palace grounds.

The origin of the Phra Buddha Sihing (literally “The Sinhalese Buddha”) is shrouded in legend and mystery. There are multiple versions of the story of how it reached the Lanna Kingdom (Chiang Mai). The version recounted here is as related in the well- researched “The Art of Sukhothai” by Carol Stratton and Miriam McNair Scott.

The great historical chronicle of Lanka, the Mahavamsa traces the origin of the Sinhalese race to when Prince Vijaya of Lala country (in present-day Bengal, North Eastern India), according to legend said to be descended of a lion, sailed into the coast of Sri Lanka flying a lion flag, on the precise day on which the Lord Buddha attained Parinirvana (passed away) in Kusinara in 543 B.C.

The history of the Sihing

The Phra Buddha Sihing we see today, is however, probably a late 15th Century replica, crafted in Siam, of the original Sinhalese Buddha. There are three similar statues in Thailand today referred to by the same name.

The statue’s long and complicated history dates back almost two millennia. Legend relates that the image was made for a Sri Lankan King in 156 A.D. as per the vision of Buddha of a Naga or serpent king. Over the centuries, the fame of this remarkable image spread throughout the Buddhist world. A thousand years later, in 1256, the legendary King referred to as Rojarat of the Sukhothai Kingdom of 13th/14th Century Siam (probably King Intaratit or Ram Kamheng) went to Nakhon Si Thammarat on the east coast of Siam, where he heard of the wondrous ancient Sri Lankan Buddha image and promptly dispatched an emissary to Sri Lanka to ask for the statue.

The king of Sri Lanka (probably Parakramabahu II) graciously consented and placed the prized image on a junk headed for Siam. The ship is said to have run aground on a reef prior to reaching its destination and the statue miraculously floated on a plank for three days before being washed ashore at Nakhon Si Thammarat. Rojarat triumphantly returned to his seat in Sukhothai bearing the precious statue, which came to be known as the Palladium, or magic protector of the Sukhothai Kingdom.

Later, between the 14th to 18th centuries, the much prized Palladium was lost and three copies were made, each of which were subsequently claimed as the original. Two of the copies moved from principality to principality as prizes of war, finally ending up at Chiang Mai and Nakhon Si Thammarat. The third and most faithful copy is the one now at the National Museum, Bangkok.

This image depicts the Buddha in the Dhyana or Samadhi Mudra (meditation posture), both hands on the lap facing upward, right hand on left, right leg crossed over left. This combination of hand and leg positions is typical of historical seated Buddha images from Sri Lanka. Two of the most famous – the 4th Century Samadhi Buddha in Anuradhapura and 12th Century Gal Vihara in Polonnaruwa both carved in granite, depict Buddha in this identical posture. The other two copies made of the Sihing depict Buddha in the earth calling or “subduing of Mara” gesture, with one hand pointing earthward in the typical style of Sukhothai images, adding credence to the view that the Phra Buddha Sihing housed today at the Buddhaisawan Chapel is indeed the most authentic copy of the long lost “Palladium of Sukhothai” from Sri Lanka.

The whereabouts of the original image are unknown. For now, the image housed in the Buddhaisawan Chapel continues to inspire the awe and reverence of thousands of Buddhist faithful as well as art lovers and visitors to Bangkok.

Sri Lanka’s role in the propagation of Theravada Buddhism

The story of the Sihing exemplifies the Lankan influence on the Sukhothai era, of which there is a multitude of evidence. Theravada Buddhism was brought to Sri Lanka from India in the 3rd century B.C by Arahath Mahinda, son of Emperor Asoka. Buddha’s teachings, hitherto passed down by word of mouth, were written down as the “Tripitaka” for the first time in the 5th Century A.D in Sri Lanka in Pali, following a convention of 1000 monks. Since then, the island has come to be considered the bastion of Buddhist scholarship and orthodoxy, home to a chapter of monks with an unbroken line of succession from the time of the Buddha, the Mahavihara sect. In 1331, the Mahavihara sect of Sri Lanka set up a branch in Ramannadesa in lower Burma, which in turn had close links with the Sukhothai Kingdom in Siam. Consquently, ten Siamese monks were sent there during the reign of Lo Thai (1298 – 1346 A.D.) for re-ordination in the Sinhalese tradition, which led to the consolidation of Theravada Buddhism as the State Religion in Thailand.

Religious and artistic links between the ancient Siamese and Sinhalese during the Sukhothai Era were further bolstered by the Siamese monk Sisatta who spent a long period in Sri Lanka participating in the restoration of the Mahathupa (Ruvanveli Dagaba). Sisatta brought back with him from Sri Lanka, two highly sacred hair and neck bone relics of the Buddha as well as a team of Sinhalese artisans who introduced new techniques and motifs into Sukhothai art. Unmistakable Sri Lankan influence is evident in the Bell (Ghantara) shaped stupa and elephant buttresses at Wat Chang Lom, Sri Satchnalai and Kala-arch decorative motifs at Wat Mahathat, Sukhothai. The revered 2nd century B.C. Mahatupa (Ruvanveli Dagoba) is thought to have inspired both Wat Mahathat and Wat Chang Lom in Siam. The typically Sinhalese style decorative motifs of inward turning Makaras with peacock tails on the arches at Wat Mahathat, Sukhothai are further examples of Sri Lankan elements in Sukhothai art.

Furthermore, since very similar decorations can be seen at the Lankatilleke temple, Polonnaruwa, built in 1342 just prior to the restoration of the Mahathat, it is believed the same Sinhalese artisans worked on both projects. Drawing from and building upon this Sri Lankan as well as Khmer, Mon and other influences, the art of Sukhothai continued to flourish, evolving into its own unique style.

Siam got its chance of returning the favour to Sri Lankan Buddhists in the late 18th Century, when after centuries of European colonial rule, Buddhism and the status of the Sangha had reached a low ebb, a Siamese monk Upali Thera travelled to Sri Lanka and played a key role in the establishment of the Siam Nikaya which paved the way for the revival of Buddhism in Sri Lanka.

Being the work of Siamese craftsmen based on an ancient Sinhalese image, the magnificent Phra Buddha Sihing remains an enduring testament to the centuries- old history of religious, cultural and artistic links between Thailand and Sri Lanka which flourished during the Sukhothai era and continue to this day.

(An abridged version of this article was published in “Sala, the journal of the National Museum Volunteers, Bangkok”)