Beyond Olu pipila and Handapane

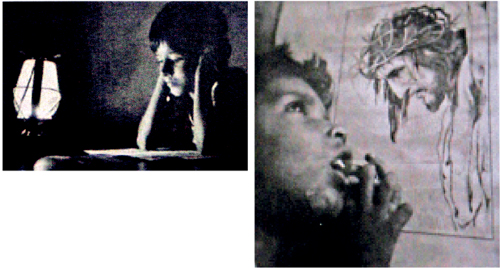

Complex photographs that appear deceptively simple (above and right)

Sunil Santha is a legend- but rather a mystic one- or so it seems in an age of tell-all tabloid celebrities. His is a mark that won’t erase, but it is hazy when you try to move beyond the music- those perennial favourites like Olu pipila and Handapane- prototypes for a whole new tradition. It is sad that the full creative and intellectual ambit of this unassuming Renaissance man in white national dress remains unknown. His name and the sepia likeness are epoch-markers- but what pulsated beneath these symbols?

This was the quest taken upon by Dr. Tony Donaldson, an Australian scholar whose interests of visual arts and music gloriously intertwine. In the mid-1990s, he was making his way through the sanctums of the Dalada Maligawa in Kandy- for his PhD on the ritual music that serenades the Sacred Tooth Relic. While in Colombo, he attended a gramophone exhibition, which was when Sunil Santha first tugged at his interest.

By then 16 years had passed since the death of the maestro. What was so alluring to Dr. Donaldson was that this man had created, from scratch, a new song idiom for a country just finding its feet after Independence. So began a survey that cannot be called ‘anthropological’, so personal its concern, so intimate its interest. The most valuable material this search yielded concerned the unknown life of Sunil Santha.

When young, Sunil Santha had wanted to study science and be an inventor, but this was not possible for a boy of modest origins. He had to study arts and be a teacher. But he proved to be as versatile in the creative domain as he would have been with machines. His unusual and unknown flair for all arts manifested itself during the years when he was expelled from Radio Ceylon, for disagreeing about a series of ill-conceived policies implemented by the radio’s music section, in the 1950s.

Sunil Santha:Symbolism was central to his photography

With time on his hands, he took to painting- among his work being landscapes- but it seems it was the camera he really loved to wield. His subjects were people- and often his children. He did beautiful chiaroscuro portraits (where contrasting light and shade create depth)- among them one of a boy (his son Sunil) studying by lamplight- the winner of a competition by the Times of Ceylon in May, 1960. The image had been titled ‘Making of Greatness’. Many of his images were hand coloured using water colours and dyes- a process requiring labour and gentle minutiae.

Another image with ingenious symbolism was taken when another son, Lanka Santha, fell and injured his hand. Partly to distract him from the pain, Sunil Santha took a picture where the crying boy looks up to a picture of Christ, whose head is bowed with the crown of thorns. The message in the Christian faith- that we can get through suffering by sharing it- could not have been better portrayed.

Symbolism was central to all his photography. They were not natural images but scripted- arranged artistically to create a particular effect. They all tell a deep story- though each may appear simple. There is one of a man, hands folded, whose face in profile stares at a distance. But a closer look reveals the glimmer of reflected light in his eye- a metaphor for wisdom.

Dr. Donaldson thinks that the beguilingly simple but really complex quality of the photography is reflected in his songs and music as well. It is easy to dismiss the songs for their ethereal lightness- as light as the wind to which he frequently pays ode- but in such instances, “people just think of the delivery,” says Dr. Donaldson: “from a listening point of view his songs appear simple but if you analyze and get into those songs, they are quite sophisticated- the substance and the content very rich. His genius lies in that ability.”

Dr. Tony Donaldson

Just as in the shadows as his hidden talents is Sunil Santha the private man. His youth was one tinted with tragedy, having lost his father to snake bite and mother to fever before he was two, and possessing great potential in science that he knew would not be realized. It was his unattained dream to be an inventor that caused him to throw all his energy into music.

These personal misfortunes left him rather tender hearted towards others. Dr. Donaldson spoke to several who were lucky enough to be mentored by him- among them Nalini Ranasinghe and Amitha Wedisinghe- and they unanimously agreed that Sunil Santha was unusual in that he never held anything back- sharing knowledge and expertise freely.

Six foot tall and strikingly handsome, he shunned popularity- which nonetheless came his way in profusion when walking around Colombo. A rather private person, the attention prompted him to buy a car.

Yet on stage, he exuded charisma. People talk about how, when in Chitrasena shows, he would hold up both hands up till the audience obediently hushed- and then only would he sing. An Indian anecdote sketches his personality vividly.

“When Sunil was studying music at Bhathkhande, there was a time when he wanted to travel back to Sri Lanka. But at that time in World War II trains were only taking military personnel. So he was thinking, how can I go back to Sri Lanka? So what he did was he went to a shop, bought a military uniform, and he wore that, boarded the train and came home in that!”

Dr. Donaldson also made an intriguing discovery which connected his research on Maligawa ritual music with the Sunil Santha compositions. The kavikara maduwa musicians who play in the inner sanctum used the laghu-guru where a short Sinhala syllable is given a shorter duration and a long syllable a longer duration when rendered in music. They also use heavy ornamentation. It is the same with Sunil Santha.

“If you listen to Sunil Santha songs, certain syllables are punctuated and he would tell singers “I want it stronger here, I want it stronger here.” This also occurs in kavikara maduwa.”

Of course, Sunil Santha created his own music. He was a great ‘collector’- as he had to be. Dr. Donaldson says “you have to have antennae listening to different kinds of sounds, different sorts of music: that’s the only way you can create a new form of music.”

“He drew on a lot of elements. A bird call could influence him- the sound of dripping water- a cuckoo bird- a distant bell tinkling- these could trigger music ideas. They could come at any time. Then he would go to his room and sit down and write it down- all of them would find their way into compositions.”

Ever the perfectionist, he would constantly revise his music, spending a lot of time in improving them.

The connection between the kavikara maduwa and Sunil Santha music had not been previously made as the Maligawa rituals remain- as always- arcane, with a few like Dr. Donaldson gaining access.

Dr. Donaldson says “I have been surprised by how close these two traditions are- even though one is entertainment and the other ritual. Though Sunil Santha married a Kandyan woman, I don’t know if he had much association with Dalada Maligawa. I don’t know whether he was exposed to the music- or even knew about it.”

Yet for the scholar this connection is fascinating. The elements common between the two traditions show that something called ‘Sinhala music’ does exist- “that it has always existed”- with a unique rhythm taken off the paddy fields and the temple drumming- the river song of the Mahaweli and the humming of Bambara bees- where both the traditional musician and Sunil Santha heard it, and caught its eternal symphony.