News

The death of Dugongs is tragic as it is both accidental and preventable

One or two Dugongs die every year in the Gulf of Mannar. Every death of these large (≈300 kg), placid, seagrass eating marine mammals is tragic, as it is accidental and heartbreaking, because each death is preventable, according to local fishermen.

Drowned Dugong – Baththalangunduwa December 2017

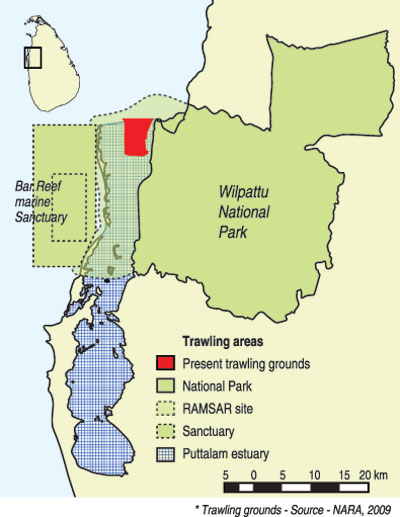

The majority of Dugong deaths occur between October and March every year. This is the calm season in the Gulf of Mannar, a time when fishermen from fishing camps in Paliwatte, Baththalangunduwa, Pookulam and Palugahathurai set large mesh (18”), super strong (36 ply) nets to catch large (≈100 kg) rays, 5-15 km to the north and northwest of the Kalpitiya Islands. Local sightings and data and international behavioural studies suggest that Dugongs become entangled in the ray nets when they move between their daytime, deep water resting grounds, to their nighttime, shallow water feeding grounds, which are the large areas of seagrass found along the southern coast of Mannar District and throughout the Puttalam estuary.

Dugongs, whose nearest living relatives are the Elephant and the Hyrax, are air breathing mammals. If they cannot surface to breathe every 20 -40 minutes, they drown. Fishermen bring the drowned Dugongs, a protected species under the Fauna & Flora Protection Act, to shore and notify the Sri Lanka Navy, which notifies the Department of Wildlife Conservation.

Earlier this year, I discussed how to prevent the accidental death of Dugongs in the seasonal bottom-set ray net fishery, with fishermen in Paliwatte, Baththalangunduwa, Pookulam and Palugahathurai. Their insights into the issue went far beyond the most predictable and probably, the least effective response to the issue – – ban the use of bottom-set ray nets!

In the fishermen’s reading of the issue, the accidental death of Dugongs is a symptom of a much bigger crisis affecting the Gulf of Mannar’s ecosystem, namely the persistent destruction and degradation of marine resources in the Puttalam estuary.Fishermen explained that the small number of fishermen who target large rays during the calm season, do so because the traditional fisheries for fish, prawns and crabs in the Puttalam estuary are no longer (economically) viable.

The same justification, the unprofitability of traditional, small scale fishing, was given as to why fishermen in the Puttalam estuary use illegal monofilament nets, why fishermen in Mandalakuuda have started installing controversial ‘box nets’, why night diving is so widespread in the Bar Reef Marine Sanctuary, why laila and sirukku nets are set too close to shore, and why some fishermen use dynamite – the other cause of accidental dugongs deaths – to stun and capture fish.

In every fishing camp, each fisherman I spoke to, returned to the same accusation that the reason fishermen engage in illegal, destructive or otherwise harmful fishing practices such as bottom-set ray net fishing is the long term degradation of marine resources in the Gulf of Mannar. In each and every discussion, the root cause of this destruction and degradation was identical, illegal trawling net fishing in the Puttalam estuary.

The fishermen’s insights are not new. In 1994, the Central Environmental Agency Site Report for the Puttalam estuary concluded that, “the use of gear such as trawls have degraded and damaged the once rich seagrass beds of the estuary. As these beds act as feeding grounds (for Dugong and Turtles) and nesting and nursery grounds for Shrimps and fishes, destruction of this habitat is very detrimental to the many animals that depend on it. It – trawling - directly reduces recruitment of fish stocks and thus negatively affects both coastal and off-shore fisheries.”

The fishermen’s insights are not new. In 1994, the Central Environmental Agency Site Report for the Puttalam estuary concluded that, “the use of gear such as trawls have degraded and damaged the once rich seagrass beds of the estuary. As these beds act as feeding grounds (for Dugong and Turtles) and nesting and nursery grounds for Shrimps and fishes, destruction of this habitat is very detrimental to the many animals that depend on it. It – trawling - directly reduces recruitment of fish stocks and thus negatively affects both coastal and off-shore fisheries.”

In response to such findings, the operation of trawl nets in estuaries was made illegal in 1996. The Inland Fisheries Management Regulations (Gazette 948/25) states that licences will not be issued for ‘any surrounding or towing net (such as madel, purse seine, trawl net)’ or ‘any mechanized boat’ in estuaries. In 2009, a report by a FAO UN consultant and NARA, concluded that the trawl fishery in the Puttalam estuary was heavily exploited, that only 25% of the catch was prawns (most of which were juveniles), and almost unbelievably, the entire trawling ground located within the Wilpattu Ramsar Wetland Cluster, was being trawled over at least 30 times per year!

Notwithstanding the Legislation in 1996, the well documented ecological consequences of bottom trawling and the Ramsar declaration in 2013, the degradation and destruction of marine resources in the Puttalam estuary has continued unabated for more than 30 years. As small scale fishermen can no longer harvest fish, prawns and crabs from the Puttalam estuary, they fish for large rays with large meshed nets, with tragic and heartbreaking consequences for the hapless Dugong.