News

Unravelling growing Arabisation

Quran Madrasas and Arabic Colleges have mushroomed in their thousands around Sri Lanka during the past decade, promoting a “pure” form of Islam imported from West Asia that is at odds with South Asian traditions.

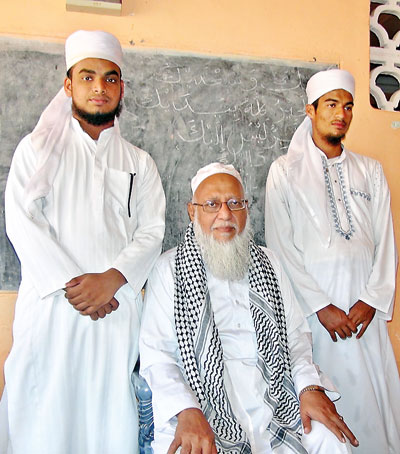

Suleima Lebbe Mohammed Aliyaar, Vice Principal of the Jamiathul Falah Arabic College in Kattankudy with two of his students in 2014

The trend mirrors developments in other parts of this region, including Bangladesh, where strong Gulf influence has seen a proliferation of largely Saudi-funded, Arab-style mosques and educational institutions. In the Maldives, Saudi Arabia has just pledged US$ 95mn towards a six-storey building complete with mosque, teaching centre and conference hall.

Analysis of available statistics show exponential growth of Madrasas and Arabic Colleges, facilitated by the Department of Muslim Religious and Cultural Affairs which also registers Ahadiya or daham schools. These have fostered greater religiosity.

Madrasas and Arabic Colleges impart teaching — often employing foreign clerics who are granted resident visas at the Department’s behest — without independent supervision or regulation. Those that enrol older students churn out adults unsuited to the job market and whose preferred career path is also that of religious instruction. Alienation with other local populations has well taken root.

In 2017, the Ministry of Muslim Religious and Cultural Affairs looked at whether a national examination could be conducted for Arabic Colleges based on a unified syllabus under the Examinations Department. An expert committee was appointed but the plan did not reach fruition.

There are now 1,669 Madrasas and 317 Arabic Colleges teaching Islamic traditions and customs, a Department spokesman said this week. Its website, however, does not reflect the recent explosion of Quran Madrasas.

It accurately places the number of Arabic Colleges at 317 with the highest concentration in the Ampara, Puttalam, Trincomalee, Kandy, Colombo and Batticaloa Districts. Additionally, there are 277 Ahadiya or daham schools, with large numbers in the Ampara, Colombo, Kegalle, Kandy and Kurunegala Districts.

Statistics, including locations, of Quran Madrasas are not published on the website. But the annual performance reports of the Department (whose Religious and Cultural Division has purview over Arabic Colleges, Quran Madrasas and Ahadiya schools) prove revealing. The Division prepares syllabuses and looks into their administration. And it also refers students from Arabic Colleges for scholarships at Al-Azhar University in Egypt, a centre of Sunni Islamic learning.

Of 60 students who applied in 2013, four Imams (priests) were selected for a three-month Islamic Sharia Education Course and seven Arabic College (Moulavi) students for the Educational Degree Course. The following year, 50 students applied and five Imams and 10 students were sent. They came back and “engaged themselves in religious activities in Polonnaruwa, Anuradhapura, Batticaloa, Ampara, Kandy and Colombo districts”.

Performance reports from 2015 onwards do not state the number of persons granted scholarships abroad. All reports say that Egyptian clerics were in Sri Lanka to explain the Holy Quran during Ramazan fasting. Meanwhile, 35 new mosques were registered countrywide in 2013. The following year, it dropped to ten.

In 2015, the number of new mosques was 190 while 1,600 Quran Madrasas had been registered with 30 added in 2015 alone. In 2016, there were 50 new mosques. The last available performance report states that 1,675 Quran Madrasas were now registered with 12 new ones–and 80 new mosques–cropping up in 2017.

Additionally, the Thowheed Jamath movement also has prayer centres. They are not Jummah mosques but they are numerous and are established in ordinary buildings.

The Department and Ministry issue resident visa recommendation letters on behalf of priests and teachers arriving in Sri Lanka to teach in local Islamic religious institutions. In 2016, approval was granted to 1,409 persons. In 2017, the number was 405 residential visas and 356 entering visas.

Madrasas are run by different Islamic sects, each seeking to draw young supporters. For instance, the Ithihaad Ahlissunnathi Wal Jamaa-Athi organisation headquartered in Gregory’s Road, Colombo 7, supports ten Sunnath Jamaath Madrasas in Galle, Eravur, Kalmunai, Matara, Hambantota and Weligama.

The Sunnath Jamaath is a religious organisation in Pakistan representing the Barelvi movement which itself subscribes to the Sunni Hanafi School of Jurisprudence and follow many Sufi practices. Thalaath Ismail, the founder of the Gregory’s Road outfit, decries on his website that the sect was “fast losing its traditional, pivotal position in Sri Lankan Muslim society” owing to the rapid spread of Thabliq Jamaath and Wahabi movements. He blames young men returning from employment in West Asia with new ideologies.

One Oddamavadi resident who had a young son said he was “not doing well in school and usually loitering about”. So his wife had asked him to admit him to a good Madrasa to learn the Quran and the religion. “The biggest problem was which Madrasa to choose,” he said. “There are so many sects and each said the other was wrong.”

Opening of Kattankudy's 58th mosque with Saudi princes and Mr Hizbullah in attendance

“I have some close Shia friends,” he said, pointing out that there was a small population of Shias in Oddamavadi. “They wanted me to put him to their Madrasa. When I tried to admit him there, others asked me if I was mad. When I tried the Thowheed Jamath Madrasas, some others said I was mad. I finally admitted him to a Thowheed Thabliq school.” There is also the Jamaat-e-Islami sect and the Deobandis have their own instruction centres.

It is documented that Madrasas around South Asia receive foreign funding, particularly from Saudi Arabia which also pumps money into mosques. In 2014, the Sunday Times witnessed the opening of Kattankudy’s 58th mosque in Sinna Kaburady Road.

The gathering of male attendees was told that the Saudi princes were in their midst. A local speaker said: “In the past, we had to collect money from villages and among ourselves to build mosques like this. Now, we get help from Saudi Arabia”. Another announced to applause that Saudi Arabia had pledged to fund a university for Madrasa teachers.

Funded by a Saudi Arabian outfit called the International Commission for Human Development, the mosque was built by Sri Lanka’s Hira Foundation of which M L A M Hizbullah, former parliamentarian and Eastern Province Governor, is patron. Kattankudy today has 63 mosques and six Madrasas (four for women) for a population of 47,125 Muslims.

Mr Hizbullah posed for photos in front of the ceremonial plaque, flanked by the Saudi visitors. Curiously, his Foundation was incorporated by an Act of Parliament only the following year, ostensibly to “protect and develop all rights of women and children”.

Foundations are a common means of raising funds and not unique to the Muslim community. And there have been longstanding questions about how they could be conduits for less desirable foreign contributions.

The East is where many of West Asia’s practices–including the black niqab and full-face burqa for women and white jubbas with long beards for men–first took hold. These have since spread far and wide.

And, as in other parts of South Asia, one main reason for these changes is foreign employment. In 2017 alone, 90 percent of Sri Lankans had jobs in the Gulf, according to the Sri Lanka Bureau of Foreign Employment. And 79 percent of all migrant employees were absorbed by just four markets: Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and United Arab Emirates.

The Colombo district contributed to 13 percent of total departures that year with Gampaha (11 percent) and Kandy (9.2 percent) next in line. The Batticaloa district accounted for 7.2 percent. Saudi Arabia employed the most number of domestic workers.

With the returnees came Wahabism promoted in Sri Lanka by the Thowheed movement, Muslim scholars say. Devoted to practising “real” or “pure”, proponents are critical of sects like the Sufis whose strand of Islam is mystical, pantheistic and influenced by South Asian traditions. This dislike has spilled into violence against Sufis on several occasions including in 2009 and 2013. And it reached a crisis on April 21 this year, with the Easter Sunday bombings targeting Christians.

| 2013:First intel on Lankans fighting with the ISIS It was in 2013 from Israeli intelligence that Sri Lanka’s Directorate of Military Intelligence (DMI) first learned that there were locals fighting with the Islamic State (ISIS) in Syria. It took the DMI by surprise, internal sources said. But they now set up dedicated teams to monitor communications. ISIS publishes a magazine called Dabiq. In it was a photo of a man named Abu Shurayh As-Silani, which was the name given by the movement to a 37-year-old school principal from Galewela called Mohamed Muhsin Sharhaz Nilam. He had left for Mecca in mid-2013 and never returned. It was found that Nilam’s elder brother went to Syria first. He followed with his wife, six children, wife’s parents and two of his wife’s brothers. Nilam’s brother’s daughter married a Sri Lankan origin Australian named Arush (phonetic spelling) and this man forged a connection with Abdul Latheef Mohamed Jameel, who also undertook a postgraduate degree at Melbourne’s Swinburne University before leaving the country in 2013. Initially, there were 36 Sri Lankans from three families in Syria. This later went above 40. Nilam died in an air raid in 2015. Afterwards, Sri Lankan intelligence found an outpouring of support for ISIS among some Sri Lankan social media users. A key player was a man in Aluthgama named Adhil who was a computer wizard. Soft copies of ISIS propaganda was shared mainly on chatting platforms, particularly Telegram. They also created their own applications with secret enclosures within that space. Adhil, like others in this movement, was young and well-educated. He adopted different personas on the internet. And this was how the grooming predominantly took place, intelligence sources said. They identified associates of the Sri Lankan ISIS supporters in Syria by monitoring who was in contact. It was a small group and not organised at the start. But they were well versed in the caliphate ideology. There were interactions, too, with an Imam at a mosque in Dehiwala but he later distanced himself from their beliefs. They grouped themselves as one organization: the Jamathei Millathu Ibraheem (JMI), led by a man named Umair from Colombo 10. They thought themselves different from other Muslims but the group also had moderates who did not want to shed blood. Some JMI members wanted to migrate with their families to Syria. But Umair changed his mind after deciding to study Islam and understand the religion. Two of the Easter Sunday bombers–the brothers, Mohamed Ibrahim Ilham Ahmed and Mohamed Ibrahim Inshaf Ahmed–linked up with Jameel because of a business and family connection. Jameel’s father was a tea business with a shop in Old Moor Street, Colombo 12. Ibrahim senior also had a shop there. The children became friends through the parents and started motivating each other. They were also associated with JMI. But there was a split between Umair’s faction and Jameel’s faction, with the Ibrahim brothers aligning themselves with the latter. They believed they needed to “do something” in Sri Lanka, which the JMI leader opposed. Another member of JMI then introduced Mohamed Zahran Mohamed Cassim to the movement. They identified him as like-minded. But he was from the East and many of the others were Colombo-based and did not take much interest in him. However, Zahran was against the Sri Lanka Thowheed Jamath and aligned himself with the breakaway National Thowheed Jamath (NTJ). Those in the JMI who wanted him shared his preaching on social media. “He took Quran verses and interpreted them the way he wanted,” said a key source. Zahran went underground in 2017 March after a clash in Kattankudy town. “What we now believe is that Jameel and the Ibrahim brothers must have established contact with and even helped him during this period for practical reasons,” he said. “I also think the Easter Sunday attacks can neither be blamed on JMI or NTJ because the violent elements split from the main groups. It was Zahran with a few people.” Intelligence was aware of the threats but towards the end of 2016, the political leadership lost interest in the ISIS and Muslim extremism element of national security. After 2009, the intelligence network flagged to the Government three post-war threats. First was the possible re-emergence of the LTTE terrorism. Second was Muslim extremism (it shifted up from being the fourth priority). Third was human trafficking and drugs or transnational crime. And the fourth was geopolitical developments. Until 2015, a meeting of the Intelligence Coordinating Committee took place every Tuesday at the Ministry of Defence. On Wednesday, there was the National Security Council (NSC) discussion. After 2016, the NSC meeting dropped to once a fortnight, sometimes once in three weeks. And the focus continued to be on the LTTE bogey rather than more recent dangers. “Our problem as that we never shifted to post-conflict surveillance mode, away from weaponised mode,” said an official who attended NSC meetings up to October 26, 2018. “Our security was always looked at through a weaponised mode that was essential when we were fighting the LTTE that had identifiable targets. Threats like ISIS and Muslim groups, where the enemy is not readily identifiable, require us to transform to a surveillance mode.” The intelligence mechanism faced another battle: “national mindset versus liberal mindset”. In 2015, the DMI made a proposal to the political hierarchy. It outlined the present situation along with how the respective groups operate and called for a mechanism with three options. One was to engage with the protagonists. Second was the introduce laws to reel them in (with a possibility of violence). And the third was a combination approach. “It was very clearly spelt out,” said an internal source. “When the Government change occurred, none of them were interested. National and liberal policies don’t work together. In this area, you can’t have two fathers. There was a division right from the top. When thinking is divided, action is divided and loyalties are divided. That was the biggest problem.” | |