News

Refugees have no place to lay their heads as Southern Governor, UNHCR squabble over site

Southern Province Governor Keerthi Tennakoon has lashed out at the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) for rejecting his offer of the Ridiyagama State detention centre to house 1,063 refugees and asylum seekers evicted from their rented homes after the Easter Sunday bombings.

But the UNHCR said the location was turned down after a joint assessment by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MoFA) and the UN for several reasons–including that it would require multiple court orders to transfer refugees and asylum seekers to a detention centre, and separate court orders to permit the accommodation of children there.

“The lackadaisical approach of the UNHCR has endangered the refugees and asylum seekers and Sri Lankan Government is left to deal with the consequences of the slow response of the UN,” said Mr Tennekoon, in a seething letter to diplomats, also shared with media. “This is not the first time this has happened. A similar situation was created with the Rohingya refugees here.”

“By keeping refugees and asylum seekers in three centres that are not equipped to house a large number of people, the UNHCR has ensured that their rights are violated and endangered the safety of women and children,” he wrote. “While urging the UNHCR to rethink their strategy in Sri Lanka, I thank the embassies who had shown interest in assisting these refugees and asylum seekers.”

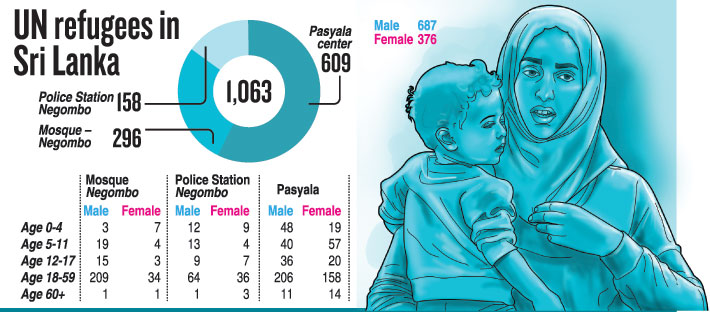

Refugees and asylum seekers are in Sri Lanka only till their claims are processed and they either return to their own countries or are resettled elsewhere. Those living around Negombo and Pasyala were evicted and are now crammed into two mosques in Negombo and Pasyala as well as the Negombo police station.

The situation at the Negombo police station is dire, with 158 people sharing a single toilet. There are 296 in the mosque in Negombo and 609 in Pasyala. Of these, 325 are children.

The situation at the Negombo police station is dire, with 158 people sharing a single toilet. There are 296 in the mosque in Negombo and 609 in Pasyala. Of these, 325 are children.

Mr Tennekoon says his offer to house all refugees and asylum seekers was supported by President Maithripala Sirisena. He says the detention centre is on 170 acres of land, is relatively isolated and safe.

“However, the UNHCR did not find the facilities at the centre satisfactory,” he wrote. “Pointing that only 250 people can live there, they insisted that there needs to be new construction. The Southern Province assured that the necessary constructions could be finished within two weeks and appointed a 12-member committee to commence procurement.”

Mr Tennekoon says that, as Governor, he has “absolute powers” under emergency laws to ensure the safety of these groups. But he admitted that he would not be able to stand against residents of the Ridiyagama area if they protested the move. Therefore, he says, he urged the UNHCR to act fast “before the window of opportunity closes”.

On the afternoon of the day that Mr Tennekoon made the offer, a team comprising multiple UN agencies and a MoFA representative visited the site but were shown a bare land with shrubs by officials appointed by the Governor. There was “nothing on it—no water or electricity supply, and no building”.

A decision was jointly taken by the UN and the MoFA that the site did not suit the immediacy of needs. However, a second visit was carried out by the UNHCR when Mr Tennekoon insisted there were buildings (which had initially not been shown to them).

The detention facility was examined, but significant challenges were identified. For instance, none of the buildings was unoccupied. The Governor offered to vacate some and fence off a separate area for the asylum seekers and refugees but this was also not deemed to be a suitable option. There was also a question of obtaining court orders.

“There were too many barriers,” an authoritative source said. The discussion went up to the UNHCR headquarters in Geneva and it was decided to go back to the Government for another solution. Mr Tennekoon, meanwhile, indicated in his letter that the window of opportunity is now closed as some residents of Ridiyagama have started protesting against his proposal.

The situation of refugees and asylum seekers in Sri Lanka has always been less than optimum owing to the adults being barred from working, and their children having no access to the education system. Free Government health facilities, however, are available.

Third country resettlement often takes years. “When asylum seekers and refugees are in Sri Lanka, they are expected to stay from anywhere between three to seven years,” said Menique Amarasinghe, Head of the UNHCR national office, at a recent UN-organised Colombo Development Dialogues. “With the shrinking resettlement environment, it’s expected that this will increase.”

In mid-2018, there were 20.2mn refugees under UNHCR’s mandate but only 81,000 resettlement allocations. Two issues have come up consistently in annual conversations with asylum seekers and refugees. “Their key concerns are access to education and access to work,” Ms Amarasinghe said.

Without a legal right to work, they have to survive on their savings or from foreign remittances. There is now more difficulty accessing those funds owing to Exchange regulations. The UNHCR provides limited monthly cash assistance to refugees (not asylum seekers). Donors also give support but there isn’t a systematic approach to ensure everyone gets assistance or that it goes to anyone that needs it.

“They are urban refugees so they need to live in cities,” Ms Amarasinghe said. “They need to pay their rent, pay for their food, clothing and the needs of their children out of whatever money they have.”

Many asylum seekers and refugees have said they manage on one meal a day. If they do engage in employment illegally, they run the risk of being exploited, underpaid or detained if caught. They have not only fled difficult situations in their home countries, they are struggling here.

“The mental issue of not being able to work is a very big one,” Ms Amarasinghe said. “They get depressed because they can’t engage in anything productive. They find it difficult that their families are struggling. And their children sometimes may be having one meal a day but they can’t really augment that. There’s a lot of frustration, there’s a feeling of disempowerment. This also affects them quite fundamentally during their stay here.”