Losses of squeezing Kandy

View(s): One day in early April, Luxman Siriwardena, Executive Director of the Pathfinder Foundation and I were at Peradeniya University. As we left Colombo early morning, we could avoid the traffic flows on Kandy road, and were able to reach Peradeniya University in four hours. But the return trip on the same day afternoon took more than five hours.

One day in early April, Luxman Siriwardena, Executive Director of the Pathfinder Foundation and I were at Peradeniya University. As we left Colombo early morning, we could avoid the traffic flows on Kandy road, and were able to reach Peradeniya University in four hours. But the return trip on the same day afternoon took more than five hours.

Perhaps today we are living in a particular time period which is characterised by the most difficult traffic jams and transport issues of Sri Lanka’s development history. About 25 years ago, this problem was not as bad as what we experience today. In 25 years’ time in the future too, we will not have this problem as bad as today. Well, for that prophesy to come to pass, we need to start working on it now!

Traffic jams and transport issues were in the centre of our discussions throughout that day. The driver, whose name was Sadaham, also made a remarkable statement in participating in the discussion: “In many other countries, Sir, they build roads for the future; here in Sri Lanka we do it for the past!” What he meant was that when we complete an infrastructure project as such, the time when it is needed is already passed.

Most beautiful

Being a past student of Peradeniya University, Luxman knew all about it well enough. He had many things to say about the university as well as university life during his time. Even by listening to him carefully, I was able to grasp many valuable lessons.

Though I have never been a student of Peradeniya University, each time when I visit there it gives me a strange feeling – mixture of both excitement and sorrow. Among so many universities that I have visited in the world, particularly in Asian, European, and Australian continents, I can say that undoubtedly “Peradeniya is the most beautiful”.

Before it was built, having observed the University site and its plan, in fact the first Vice Chancellor of the University, Sir Ivor Jennings had reportedly said that “no University in the world would have such a setting.”

The old glory of the University is still visible through what is remaining. But it is not difficult to imagine that much of it had decayed and faded away over the past 70 years. How could a university survive in isolation, when it was an integral part of a political-economy that was decaying over the years?

Squeezing city

After completing the work that we attended, we could not resist the invitation for lunch by Wasantha Athukorala, Professor in Economics at Peradeniya University. Our lunch time took more than two hours at Peradeniya Rest House, not because of the lunch, but owing to a long interesting discussion – again on traffic jams and transport issues.

The discussion was based on a research project that is being carried out by a research team of the Peradeniya University on the “Cost of Road Traffic Congestion in Kandy City.”

The discussion was based on a research project that is being carried out by a research team of the Peradeniya University on the “Cost of Road Traffic Congestion in Kandy City.”

Kandy is a small city with narrow roads and streets, already squeezed by surrounding mountains, waterways, buildings, and heritage sites; perhaps, its further expansion might be only vertical – underground and overground, as space for horizontal expansion is limited.

Increased traffic flows have already made it a bottleneck; if you want to cross the city which is limited to about 10 – 12 kilometres from one end to the other, it is better to set aside at least one hour for that during the rush time.

Traffic congestions originate from an economic problem among other issues, while the traffic congestions produce an economic problem among other issues. I recalled Sadaham’s remark that “we plan for the past!”

As a nation we did not make adequate planning in the past for the emerging traffic flows in the future. And when we plan and complete a project, it would have been better for the past than for the present.

People and vehicles

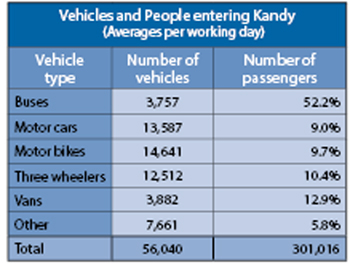

Each working day about 301,000 people – more than double the number of city dwellers, enter the Kandy city through its three main transport corridors – Peradeniya, Katugastota, and Thennakumbura, according to the preliminary findings of the research.

The average number of vehicles entering the city amounts to more than 56,000. There are over 40 schools within the city with approximately 65,000 students and 3,000 teachers.

More than half the people entering Kandy city come in over 3,750 buses. About 20 per cent of people come in over 12,500 three wheelers and 14,600 motor bikes. Over 13,500 motor cars carry 9.0 per cent of the passengers, but dominate the traffic flow occupying much of the road space.

It is quite strange that the cheapest transport mode which can also help to reduce the traffic congestions – the trains, carry only 6,000 people to Kandy, which is less than 2 per cent of the total.

Data on vehicles and people entering each day to Kandy city, clearly point to one thing: Failure of the public transport system. An efficient and decent public transport system would result in a substantial reduction in the use of motor cars, three wheelers, motor bikes, and vans. More advanced transport modes such as subway rail transit system or a light rail transit system can reduce not only the private vehicles but also the number of buses on roads.

No other choice

While Wasantha was explaining logically, how one additional bus can remove so many motor cars from the road, as usual Luxman interrupted putting him on the spot: “How many times a day do you go to the city?”

“I have to go two or three times a day, mostly to transport my children going to the schools there.” Wasantha answered. It invited the second question from Luxman: “I hope it is by your car; why don’t you think of using public transport, instead of your private car?”

“I have to go two or three times a day, mostly to transport my children going to the schools there.” Wasantha answered. It invited the second question from Luxman: “I hope it is by your car; why don’t you think of using public transport, instead of your private car?”

Wasantha smiled and answered: “Actually, we have asked that question too from the motorists. Even if we increase the number of buses, motor car users prefer their car.”

He continued to explain: There are three reasons why they don’t change: Convenience, Timing, and Safety. People who can afford to travel by private vehicles, don’t want to choose inconvenient and even indecent bus rides. Secondly, they don’t want to waste time in the bus halts and inside the buses; they don’t have a timetable, neither do they have a sense of timing. Thirdly, people prefer private transport as a safe travel mode especially for their children, females, elderly and sick people.

Even the people who travelled by buses, chose the bus not because they like it but because they have no other choice!

Time loss

The total losses of traffic congestion are numerous: These losses include (a) the economic loss of productive time of commuters, (b) financial loss due to excess fuel consumption, (c) environmental loss due to excess carbon emission, (d) additional cost of health hazard of the people and, (e) the additional cost of payments to those who work “unproductively” in the context of traffic congestion.

While assessments of some of the above losses as such are still being carried out by the research team, gross estimates show that the economic cost of “time loss” is about Rs. 296 million for a 5-day week, and well over Rs. 1 billion a month, taking Rs. 2000 as the wage rate per day.

The research team has arrived at the economic cost of time loss by taking the difference between the “actual speed” of vehicles and the “regulated speed” limit within Kandy city. On average each commuter is wasting 48 minutes a day on the road so that the time lost by all the commuters would be 236,900 hours a day.

The big question is how much we lose as a nation due to our inefficient and inconvenient modes of transport system and increasing traffic congestions in the country. We should plan for the future, not for the past! (The writer is a Professor of Economics at the University of Colombo and can be reached at sirimal@econ.cmb.ac.lk).