News

Avant Garde ship captain still languishes in Sri Lanka; sick, but unable to return home

Gennadiy Gavrylov :“Nobody has explained why I’m sitting in Sri Lanka for four years". Pic by Indika Handuwala

The Ukrainian ship captain is a sick man. Serious blockages in his heart need immediate surgery. But Gennadiy Gavrylov doesn’t dare to go on that operating table – because if he dies, he won’t have his family around him.

Gennadiy, now 52, has been in Sri Lanka for four years. Ten months of this were in remand prison. While his passport is now in his possession, his bail conditions prevent him from leaving the country. And he is desperate to go home.

In July 2015, Gennadiy boarded the Avant Garde vessel which was anchored in the Red Sea. It belonged to Sri Lanka Shipping Co Ltd, a private entity, but was time-chartered to Avant Garde Maritime Services Ltd (AGMSL) along with another ship named M V Mahanuwara. The Chairman of the Avant Garde Group is Nissanka Senadhipathi.

A time charter is the hiring of a vessel for a specific period. The owner, Sri Lanka Shipping Co, managed the vessel. But the charterer, AGMSL, selected the ports and directed the ship where to go.

Gennadiy – the graduate of a maritime university in Ukraine – was to be captain on six months employment with Sri Lanka Shipping Co. He commanded a crew of 21 members. But he had no contract with AGMSL which was using the vessel to run a sea marshal operation.

On board were weapons belonging to Rakna Arakshaka Lanka Ltd (RALL) under the command of an ex-Colonel named Don Thomas Albert who was a RALL employee. Operations Manager Nilupul de Costa oversaw matters for AGMSL.

The Avant Garde vessel was stationed in the Red Sea. It also had many sea marshals. Passing civil ships that were entering waters susceptible to Somali pirate attacks would hire weapons and sea marshals from Avant Garde and take them on board. It was lucrative business and there was frequent change of men and weaponry.

But Gennadiy had nothing to do with that. “I am the driver of the vessel,” he explained. Around one-and-a-half months after he took command of the ship, his company ordered them back to Sri Lanka to renew documents issued by the Director General of Merchant Shipping.

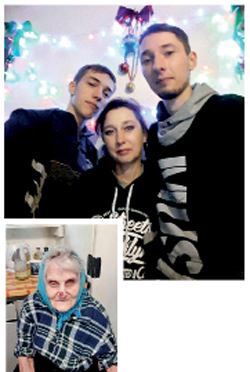

Gennadiy’s family is afraid to come to Sri Lanka

On the morning of October 5, 2015, Gennadiy says, they waited outside Sri Lanka’s territorial waters off the Galle Harbour for permission to enter because they had dangerous cargo on board. But the Sri Lanka Navy later approached the vessel and took command for reasons nobody knew at the time.

“I was afraid,” Gennadiy said. “For the first time in my working life, this was happening and nobody explained what my fault was. The Navy came on board and was speaking with Nilupul. For my part, I gave the officer all the ship’s documents, along with necessary permissions. We didn’t violate any international law. And I was not responsible for the weapons or the sea marshal service.”

It was the beginning of a nightmare for Gennadiy, one that has impoverished him and his family. His mother, born in 1937, and mother-in-law have both suffered strokes and are paralysed. And his wife was treated for depression. He once earned US$8,000 a month as a ship’s captain. Today, he survives on an allowance of Rs 50,000 and has only one good shirt to wear to a meeting.

Gennadiy and his crew waited several days on their ship. Every nook and cranny of it was searched. Statements were recorded from him and the others by the Criminal Investigation Department (CID).

“When the police came on board, I asked, ‘Sir, what is my fault?’” Gennadiy said. “I am the captain. I’m not responsible for the weapons. My business is safety and navigation. The CID officer told me that not to worry, this was a Sri Lankan internal case, a temporary situation, and that I could go home after three or four months.”

But when a new CID officer took over, he told Gennadiy that, whether he was “guilty or not guilty, you will be a long time in Sri Lanka”. And he wouldn’t tell him what he was accused of. His prophesy, however, came true.

Gennadiy’s contract with Sri Lanka Shipping Company ended amidst the Avant Garde saga. His employer requested the harbour master permission to release him. He replied that the Magistrate had not approved that.

On June 23, however, the Galle Magistrate ordered Gennadiy’s discharge and he was free to return to Ukraine. But later that same afternoon, he was arrested without being given a reason for it. He was given a Sinhala language statement to sign. He refused. His phones were taken so he could not immediately contact a lawyer. He was taken to the Galle Harbour Police before being produced in court.

The same Magistrate ordered his remand. “After that, I spent 10 months in prison,” he related. “I was never charged. It’s been four years now. I came here when I was 49. On every court date, the prosecutor asks more time for investigation.”

One of the main charges against him is that he had navigated his vessel into Sri Lanka’s territorial waters without permission. He insists this is not true. And a fundamental rights petition he has filed says the Avant Garde was steaming at 15 nautical miles from the baseline.

In terms of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, the territorial waters of a nation is determined as not exceeding 12 nautical miles measured from the baseline. This case is still in court.

Back home, Gennadiy has two sons. The older one, 27, is an IT professional. The younger one, 19, studies at the same maritime university he attended. Gennadiy’s father was a chief engineer on civil ships. His mother was a teacher. He started his job in 1987. He first worked as a seaman, then motorman, engineer, navigator and ship’s captain. He climbed the ladder step-by-step.

In August 2017, Gennadiy collapsed at the Supreme Court where his fundamental rights petition was being examined. Tests showed he had serious heart ailments. “It was a problem that began in prison,” he said.

Being locked up was a shock to him. He shared his cell with a Bulgarian. “I felt very sad, very bad,” Gennadiy reflected. “It was always closed and we needed permission to go outside. I had to sleep on the floor with a mattress.”

It was found Gennadiy suffered triple vessel disease. He swallows five tablets every morning, six every evening. Doctors have recommended open heart surgery.

“It’s a serious operation but I’m not going for it because my family isn’t here,” he said. “Think how you will feel if you go to another country and they cut you open. Whether you will live or not is a big question.”

Gennadiy’s family is afraid to come to Sri Lanka. “Nobody has explained why I’m sitting in Sri Lanka for four years,” he said, eyes red. “I can’t explain.” His wife of 28 years is now shackled with the responsibility of caring for two paralysed mothers.

With his income gone, finding money has become a challenge. He is the breadwinner. “My family don’t have money,” he said. “I have lost everything. My family lost everything. Four years…”

Today, Gennadiy has only one hope – one request. “If I’m guilty, punish me and deport me,” he begged. “I will sit in prison in my country. But if I have done nothing wrong, please let me go.”