News

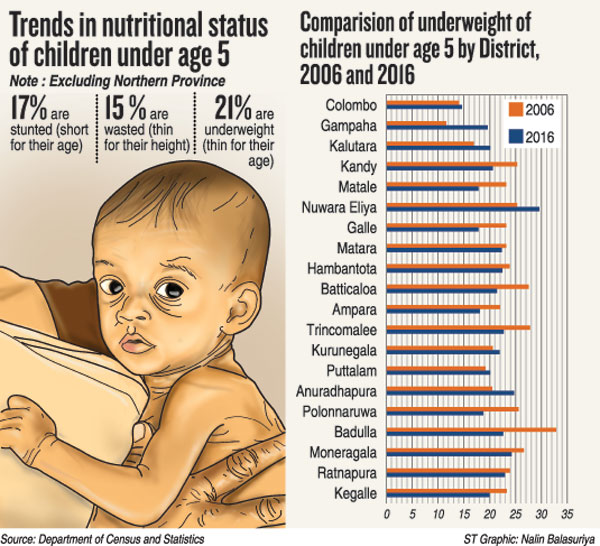

Poor nutrition harms children and stunts nation’s growth

The death through starvation of an 11-month-old child in the Hambantota district last week has cast doubt on the health sector’s effectiveness in making sure youth are properly fed.

The parents of 11-month-old child who died reportedly of starvation

While media reports speculated that the infant died mainly due to economic reasons and the family could not afford appropriate nutritious food, nutritionists say the dysfunctional state health mechanism and the mother’s poor knowledge of nutritious food were contributory causes for the debacle.

One in three children younger than five years is anaemic, the National Nutrition Policy of Sri Lanka reveals. This fate is attributed to inappropriate feeding and caring practices, inadequate knowledge and caregivers’ time constraints.

Professor Janaki Gooneratne, nutritionist and former head of the food department of the Industrial Technical Institute, said despite the Health Ministry’s effort to eradicate under-nourishment in children through various programmes, mal-nutrition prevails because pregnant and lactating mothers, through lack of understanding, resorted to inappropriate complementary feeding.

In this age of television, mothers both in the rural and urban areas, are influenced by infant products marketed through commercials.

Prof. Gooneratne said although a child may be given nourishing, locally-blended food (a combination of rice, peanuts and green gram/cow pea), most mothers go for the commercial products sold in shops at exorbitant prices.

“Either they do not want to follow the grandmother’s formula or are carried away by the media which portray commercials glorifying the supplementary foods available in the markets,” she said.

“The poor man who cannot afford luxury food fails to realise that similar nutrients can be obtained from our locally-available vegetable and cereals.”

Prof. Gooneratne referred to Poshitha, a local children’s food product made from local cereals that was devised in the mid-1990s by a non-governmental organisation. Model factories in Puttalam, Hambantota and Anuradhapura were set up to produce the food but the factories soon closed due to political interference, she said.

Professor Harendera de Silva, a member of the College of Paediatricians who has carried out extensive research on child malnutrition, said the public had been misled by professionals.

Professor Harendera de Silva, a member of the College of Paediatricians who has carried out extensive research on child malnutrition, said the public had been misled by professionals.

He said professionals were being driven by politicians and the food industry to convey the wrong message, the politicians for their own gain and the food industry for commercial gain.

He emphasised the importance of energy content in a meal and this, he said, could be achieved by adding oil to food. He said that he had advocated adding oil in infant food in all infant preparations to increase the energy density of food. Prof. de Silva advocates adding 1.5 teaspoon of oil in infant food prepared in homes.

One major problem is that needy children in rural areas are neglected by the Maternal and Child Health Programme of the Health Ministry.

Although ministry’s medical staff carry out various programmes on evidence-based intervention on nutrition recommended by the World Health Organisation its network fails to operate in rural areas and the plantation sectors.

A 2016 World Bank report, “Tackling Chronic Under-Nutrition in Sri Lanka Plantations” said under-nutrition was not only an economic problem but also a behavioural and cultural problem for this country.

Surveys showed mothers in the estate sector were unsure of introducing complementary food such as fish, meat and eggs to children and ignored the importance of introducing such food in six months.

Also, traditional beliefs that eggs cause phlegm and fresh milk triggers allergies, skin rashes and shortness of breath stopped parents from giving children nutritious food.

Also, traditional beliefs that eggs cause phlegm and fresh milk triggers allergies, skin rashes and shortness of breath stopped parents from giving children nutritious food.

The report said Health Ministry programmes failed to reach the targeted population, lacked resources and was not properly monitored or coordinated.

The report recommended comprehensive behavioural change to reach mothers and childcare providers and creating awareness on risks to long-term health and the economic impact of stunted growth during the first 1,000 days of life.