When gallstones need attention

View(s):

A few years ago, a bright young woman came into my office.

“It seems that I have gallstones, ”she said. I waited sphinx like. “You are the person to take them out I hear.” I smiled acknowledging the compliment “but are they troubling you?”

“Not a bit,” she said, “but I need it out all the same.” My smile faded. “I don’t operate on patients with gallstones unless they have problems.” She looked at me brightly “but I’m off to the Australian Antarctic Base for a year, and I’ve been told that they are not coming with me.”

Now, this was different. Medical evacuations from any Antarctic base are a nightmare and highly dangerous for many people apart from the patient. So a general rule is that people with gallstones, an intact appendix, or a hernia need to have this sorted before they leave. The chance of having an attack from known but asymptomatic gallstones is still quite low about 1% to 2 % a year. But dealing with a complication of gallstones in the Antarctic Base is another.

I directed her toward the scales, and height measure in the corner of the room. Her BMI was 28; not obese, but well covered. “I suppose I am fat, and that’s why I have ‘em?” I hastened to reassure her “the aphorism we use is Female, Fair, Fertile, Fat and Forty, but like all aphorisms, only partly true.” Men do indeed get gallstones but much less commonly, obesity (a BMI above 30) or rapid weight loss, the contraceptive pill, some particular communities (in South America for instance) are particular associations. Up to 10% of women develop gallstones during pregnancy, but most of them disappear. The population prevalence in most western societies of gallstones is somewhere between 10% to 20%. My patient, let’s call her Liz, had one child, was 35 years old, and had been on the pill on and off since she was 18.She had no previous surgery. Reasons enough.

We sat down. She needed to know what this was all about. She was also a scientist, which helped.

I got out a sheet of paper, and wrote down her name and the date. I drew out an outline of a liver and went into my usual spiel. (I have done some thousands of these operations over the years so it is quite automatic).

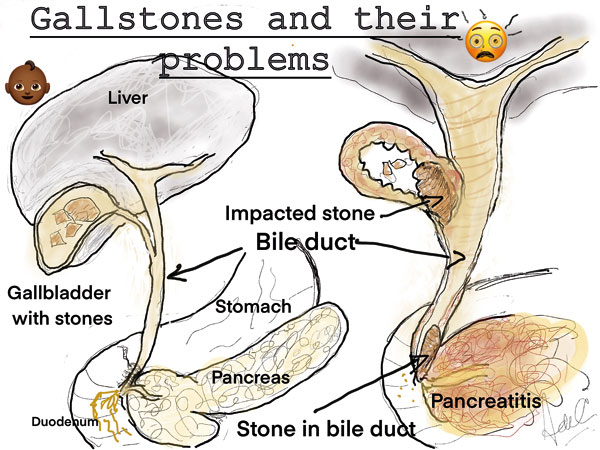

“The liver makes bile. Bile is a clear yellow liquid which contains cholesterol, bile salts and phospholipids. Bile usually progresses down the bile duct toward the duodenum (I quickly draw these) and pass through a sphincter muscle into the duodenum. In the duodenum it has several functions including the digestion of fat. When the sphincter muscle is closed the bile travels back into the gall bladder where it is concentrated. When you eat, the gall bladder contracts sharply, bile fills the main bile duct and is rapidly emptied into the duodenum, the sphincter being relaxed. In between meals the constituents of the bile in the gall bladder being concentrated, may promote the formation of crystals of cholesterol. These may grow and add on other compounds as they do to form gall stones. Stones can lie in the gall bladder and do no harm whatsoever.” I paused for emphasis “but they can unleash hell.”

I pointed to the diagram, and drew in the scenarios, as I drew several stones in the gall bladder. “As the gall bladder contracts after food the stones can move into the bile ducts and damage them or cause an obstruction. Infections then in the gall bladder and bile ducts can lead to severe pain, septicemia and jaundice (where bile escapes into the bloodstream). A particularly nasty complication is Pancreatitis when the stones damage the pancreatic duct at the lower end of the bile duct. All these complications of gall stones are miserable and dangerous and can be quite difficult to deal with.”(see diagram)

“Well I am going to be spared that, thank heaven,” she said. “And what’s more’ I added “I can take out your appendix easily enough at the same time.” I had realized by now, that she had a clear case to have both organs dealt with.

A frown creased her otherwise perfect forehead. “No big scars, I only want keyhole surgery.”

“As a matter of fact” I said as I was getting up her pictures on my screen“we have a bit of predictive science on this subject, worked out in Cairns in JCU,( by young Dr. Janindu Goonawardena, ex S. Thomas College and presently an Australian surgical trainee). What we worked out in a model that we have validated, is that there are 5 variables, two demographic, and 3 variables derived from the Ultrasound pictures, which allow us to provide a “risk” of conversion of the operation from keyhole to Open, or conventional surgery. The two demographic factors are obesity (BMI> 30), and previous abdominal surgery. Her US pictures showed her gall bladder to have a thin wall, there was no impaction of a stone in the neck of the gall bladder, and her bile ducts were not dilated. So we now put all these 5 risk factors into a series of graphs called nomograms, and easily read out this risk for each patient. I am able to reassure Liz that her risk of conversion is very low indeed, around 1%.

Liz was very reassured by this. “What about complications?” she asked. She was obviously very well read, and had done her homework. But as I do with everyone, spelled out the detail of the most feared complications on her diagrams.

‘If I had to give you all the possible complications of this surgery, we would be here all night. Laparoscopy itself (where we introduce Carbon Dioxide gas into the abdomen to distend it can cause complications, but these are very rare. The complication that you must be aware of is injury to the bile ducts. This may become obvious at surgery but may present as a problem weeks or months later. Injuring and scarring of the bile ducts can cause pressure on the liver resulting in jaundice, and liver damage. This is a life threatening problem, and takes a great deal of skill and resources to sort, usually in a specialist unit. The risk is very small between one in 200 or 300 operations. But is never zero.”

“What are the consequences of losing my gall bladder?” This was a good question, and I referred her to the diagram. “Without a gall bladder there is no reservoir function, and bile leaks continuously into the bowel. Most people don’t notice any change, some do open their bowels more frequently.” She looked at me with a glint in her eye,”I will look forward to that.”

I examined her abdomen which was soft and non-tender, taking note that her umbilicus was clean and tidy, and there was no hernia in the region. I entered all my observations on the sheet of paper, and asked her to sign it. We now had an agreed record of our meeting and I immediately printed out a copy for her.

“How should I prepare myself for this?” I looked at the details of her social history which had been already recorded, “you neither smoke nor drink, which are major problems having an operation. You are on no particular drug (she had come off the pill about 3 months previously), but we better get a pregnancy test done, as we often use X rays during these operations. I get really obese patients to go on a rapid weight loss regime supervised by a dietitian, but again none of this applies to you.”

We went over the consent process, and she was on her way.

I met her post-operatively six weeks later. She was leaving for Antarctic Base a fortnight later.

“Well that was pretty easy,” she said. It was pretty easy for me too, but I did not tell her that, as I shook her hand and wished her well.