News

Ranger’s death triggers call to recognise job risks in jungle

A wildlife ranger was tragically killed this week when an elephant whose gunshot wound he was trying to treat suddenly turned and attacked him.

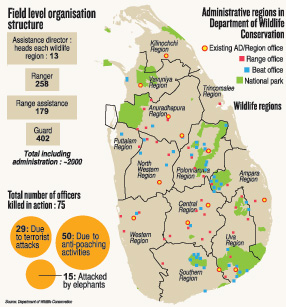

Ranger B.M.C.K. Basnayake was the second wildlife officer killed by an elephant this year and the 75th ranger to die in the course of duty since the Department of Wildlife Cons ervation (DWC) was established.

ervation (DWC) was established.

The death occurred when a three-member team from the Nikaweratiya veterinary unit of the Kurunegala Wildlife Range was attempting to treat an elephant locally known as “Kara Patiya” that had an infected gunshot wound in one leg.

The team shot the elephant with a dart containing sedatives and followed the elephant through the jungle, waiting for it to fall unconscious so they could tend its wound.

The sedative, however, proved ineffective so the rangers moved closer in to try and shoot a second dart into the injured animal.

But the angry elephant turned unexpectedly and chased the wildlife officers. Mr. Basnayake was a fraction too late getting to safety as he tried to give the other two officers time to get away, and the elephant attacked him.

According to some sources, Mr. Basnayake, a wildlife guard with 10 years of experience, had been carrying a loaded gun but had not used it against the elephant.

Ironically, Mr. Basnayake’s untimely death occurred just a week after World Ranger Day on July 31, which honours wildlife and park rangers across the world who have been injured or lost their lives in the line of duty.

Mr. Basnayake was the 75th wildlife officer killed on duty since the DWC was set up in 1949.

Fifty of the rangers died fighting wildlife crime, being murdered by poachers or falling victim to deadly traps set for animals by poachers. Fifteen were killed during operations related to elephants.

Worldwide, 149 rangers died in the course of duty last year, according to the International Ranger Federation (IRF), 45 of them killed by poachers, militia and other assailants. Another 23 lost their lives in encounters with the animals they were protecting.

Rangers face increasingly complex problems.

“The behaviour of wild animals has changed over time,” an experienced officer who wished to remain anonymous said. “Elephants seem to have become more aggressive as a result of the bad experiences they have had with humans. This has increased the risks faced by wildlife officers in the field.”

Human population growth is another problem, the officer added. “Decades ago, there were only few villages bordering the areas where wildlife roam. But now the wildernesses are surrounded by villages that block the routes the animals take to find food and water, so the conflict with wild animals – particularly with elephants – has increased.”

Mr. Basnayake leaves behind a wife and two children, one a year-old toddler and the other aged five. The families of rangers who are killed on duty receive normal government compensation and additional funds from the Wildlife Welfare Fund but this money is often inadequate even for basic needs such as schooling, the IRF said.