Gut feelings and the perils of Socrates

The ward round has been completed. We have seen and discussed several patients who had bowel (colon) resections. As this is also the weekly teaching round we have the usual complement of training registrars, residents and medical students. I send them off to get coffee, and we reconvene in the tutorial room next to the ward.

The ward round has been completed. We have seen and discussed several patients who had bowel (colon) resections. As this is also the weekly teaching round we have the usual complement of training registrars, residents and medical students. I send them off to get coffee, and we reconvene in the tutorial room next to the ward.

I’m ready to do a standard exercise, relating to the function of the colon.

They settle in, quite prepared to be bored.

I begin. “Well, we saw today a number of patients who had bowel resections. We seem to be able to take out the right half and the left half of the colon with impunity. Indeed we can take out all the colon. The colon is a pretty big organ, is it not?” I have their attention, because clearly this is going somewhere.

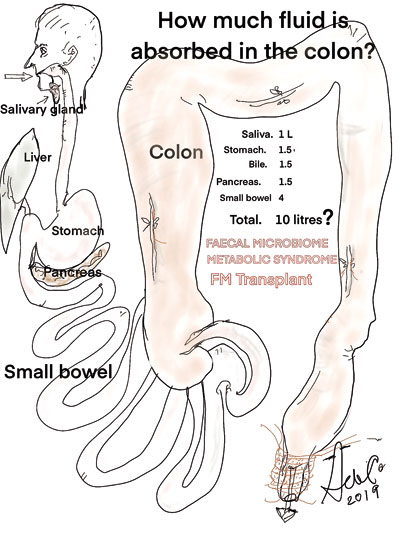

“So what,” I ask, “is the function of the colon.” Two of the more adventurous put up their hands; “Water absorption,” they both opine. “Ok, but how much water?” The numbers offered up are 2 litres and 5 litres. “Ok,” I say. “Let’s work it out.” Stepping up to the white board I draw an idealized gastro-intestinal tract. “The GI tract after all is a single tube, with a few organs connected to it. It starts at the top, and ends at the bottom. So what organs are connected?” The students fill that in easily enough, but leave out the salivary glands. I add this to the picture. None of them has much of an idea about what comes out of each organ over 24 hours, and with help from the registrars we fill in the blanks. It is clear to everyone by now, that a trap is being set, and the students, now wary, are no longer volunteering.

Meno, so Plato tells us, took one of his slaves to Socrates, who wished to demonstrate that knowledge could be “recovered”, though with some help. Socrates drew a square in the sand, and invited the slave to double its area. As expected the slave doubled the sides. Now, clearly the slave knew no geometry and was unlikely to have heard of Pythagoras. So Socrates, drew his triangles and made the slave understand his error. Meno thought that he had been hard on the young man, but Socrates said that this “numbing” was good for him.

As an educator, I am aware that this tradition of humiliation has no place in the modern approach to teaching and learning. But as this example shows there are traps for the unwary.

Back to my tutorial, I point to the drawing “So, we have a combined volume of 10 litres. How much of this passes into the colon? How many of you think that the figure is between 5-10 L”. Half the students rather nervously put up their hands. The time has come to reveal the deception and prevent any real harm. My Senior Registrar is waiting to be invited, as he has been through this exercise before. He walks up to the whiteboard.

“Prof de Costa has deliberately misled you. Most of this 10 litres of fluid is reabsorbed in the small bowel, particularly the lower third of it, the ileum. So less than a litre gets into the colon, and about half that is absorbed -leaving between 300 of 400 ml to pass out.”

I prompt my registrar. “The colon is a big organ, so is its only function to absorb a half litre of water?” He gestures to the diagram. “The small bowel is constantly churning around and mixes the gas that you swallow in its content, an emulsion that we refer to as chyme. The colon is capacious and sedate; this allows the gas to separate as the fluid itself thickens toward the end of its journey. And, as you all know,” he is beginning to enjoy himself, “the rectum and sphincters can pick the difference between gas and solid, and deal with each appropriately and separately. And make civilization possible.”

“So why is this relevant to our patients?” I ask. He resumes, “All patients having bowel resections need to be informed of both complications and consequences. If a large amount of bowel is lost, separation of gas and liquid may not occur and impair the distinction, so they may always have to sit down when they feel the need. There may also be issues related to continence.” He walks to the whiteboard and points out the ileum. “This is the real engine of absorption, and if this has to be resected for any reason, for instance Crohn’s disease, a large amount of fluid will get into the colon, most of which will be lost. These patients face severe dehydration, and keeping them alive is sometimes a battle.”

A student puts up her hand. “But is there not a metabolic function of the colon, is it not more than a sponge and a conduit?”

I know the student, who had a PhD in Molecular Biology before she went to Medical School. I invite her to come up to the front. She writes down a figure next to the colon in the illustration. “That is an estimate of the numbers of organisms in the normal colon.” She writes some names, and goes on to describe them, explaining that gut organisms can be divided into two broad Phyla (categories). “These are the Firmicutes and the Bacteroideae and between them there are about 9000 species. Modern techniques allow a small sample of stool to be examined for gene sequences to work out proportions (metagenomics) to see how they vary in the individual and in disease states. There seem to be many ways that these groups relate to the rest of the body. One way is that these bacteria ferment residual complex insoluble carbohydrates forming Short Chain Fatty Acids which are absorbed into the bloodstream.”

She returns to the whiteboard. “There is an explosion of research interest into these relationships, between the Faecal Microbiome, Diabetes, obesity, liver disease, atherosclerosis, which are part of the Metabolic Syndrome, and many other conditions. An emerging therapy, FM Transplantation is now being used in certain clinical situations. The Chinese though have used this kind of therapy for 1500 years.”

My registrar catches my eye. We are needed elsewhere.

I thank the student for reminding us of this important subject. “We do need to have a separate session on the Faecal Microbiome, as it is a fascinating topic and a prolific area of research including in our University.

“So, to sum up, remember that your patients scheduled for bowel resections need to be informed of the complications of these operations, which perhaps will affect one in 20. Quite separately there are consequences of bowel resections, and you should remember this when discussing possible outcomes with your patients.”

The students get out their phones and take a picture of the whiteboard. They have had a productive half hour, and nobody has been “numbed” thankfully. My registrar and I take the stairs down to the Operating Theatre, where I will be assisting him doing a colectomy. “How many of these have you done?” he asks. “Enough,” I answer, “Quite enough.”

(The writer is Associate Prof. of Surgery, James Cook University (JCU), Cairns, Queensland, Australia)