Tracking the effects of networked protests

Zeynep Tufekci: Asking crucial questions

Zeynep Tufekci is no stranger to protests. The 90s found the Turkish social scientist in Chiapas, watching as the Zapatistas clashed with the Mexican state; in 2011, she was in Tahrir Square in time for the revolution; that same year found her in lower Manhattan for Occupy Wall Street, where the 99% gathered to demand the 1% take note; in 2013, she was in Istanbul, at the TaksimGezi Park where protestors would inspire support across Turkey. And those are just the ones where she was present in person: in the era of the internet, protest transcends pure geography.

An associate professor at the School of Information and Library Science at the University of North Carolina and a faculty associate at the Berkman Center for Internet and Society at Harvard University in Massachusetts, Zeynep has dedicated herself to studying the social effects of technology. “It can be interesting to be in the middle of historic stuff,” Zeynep says now, explaining that to step into a protest is to be surrounded by people who are powered by deep emotions, often very optimistic, convinced that they and their friends will drive the change they want to see. In that space, Zeynep plays the role of observer, talking to people, following how things evolve and keeping tabs long after the cameras have left the scene.

Today, Zeynep is not in Colombo to attend a protest, but has just left one behind her. She chose to fly through Hong Kong from her base in the US and found the airport in chaos. “I just barely managed to make it out of the Hong Kong airport because there were blockades, there was commotion, the police came in, there was pepper spray, people screaming…” When she saw an opening, Zeynep dashed past the barricades and found, finally, a flight that would bring her to Sri Lanka.

A computer programmer and social scientist by training, Zeynep is interested in the role social media plays in social movements, and in how big data and artificial intelligence are increasingly shaping the proprietary algorithms that govern many of the platforms we engage with today. She is simultaneously an optimist and a realist. She deeply values the social, economic and cultural advances that technology can enable, but balances this with her engagement with real world complexities: the exploitative ways in which states, businesses and other actors with an agenda can co-opt the same technologies that gave ordinary citizens a voice and a platform, and turn them back on us.

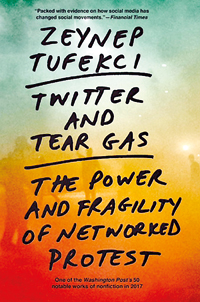

In her 2017 book Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest, Zeynep argues that even as technology empowers social movements, for instance by enabling greater numbers of people to gather more quickly than ever before, it also simultaneously weakens them, allowing us to simply leapfrog over the essential legwork, the long drudgery of organizing and mobilising people that translates into protests that have a kind of institutional capacity to take the next, critical steps: that can compromise between various factions within the movement itself, have a leadership capable of negotiating with the opposition and follow through on their agenda long after the crowds have gone home. Instead, today’s hashtag protests can bring large numbers of people together, but leave them without leadership and without a path to achieving their goals.

Zeynep’s book

Zeynep tracks not only social dynamics among the protestors but observes how the powers that be respond. Increasingly, such responses have opted not for brute force in terms of cutting off the internet, but in muddying the waters by overwhelming people with misinformation, troll attacks and contradictory statements. Recently, Sri Lanka’s decision to block social media in response to events like the 2018 constitutional crisis and the Easter Sunday Attacks is something that interests her.

“I basically came out the first chance I got,” she said explaining that as an academic her interest is really in speaking with a wide range of people and gaining a sense of the realities on the ground. How do we respond to hate speech while allowing people the freedom to have an opinion? How do we ensure there is transparency online? For Zeynep, these are the big questions – and there are no easy answers.

“And the answers for Sri Lanka or Brazil or India, might not be the same as they are for the US, UK, or Germany because countries are at different points in history, different places in the world, different moment in that country’s trajectory,” she says, adding, “We don’t want a new form of colonialism where there is a set of decisions that are made far from these places without necessarily keeping the interests of the people here in mind and are more in the service of these large-scale commercial enterprises.” She would also like to see things like the new regulations that Facebook rolled out in the EU to provide greater transparency around political advertising ahead of the European Parliament elections become available in Sri Lanka and other places as well where similar pivotal transitions are unfolding.

Meanwhile, her concern around the influence of behemoths like Facebook, Google and Amazon has only increased as the role of artificial intelligence and big data has grown. Researchers are finding that algorithms designed to boost advertising revenues and sales can threaten to violate our privacy and agency in profound worrying ways.

In this context, Zeynep would write in her column for the New York Times: ‘Unless they are properly regulated, in the near future we could be hired, fired, granted or denied insurance, accepted to or rejected from college, rented housing and extended or denied credit based on facts that are inferred about us.’ She says whether the facts are correct or not is not really relevant – either situation presents its own challenges.

In the end, it’s a fascinating time to find herself in this field, not just in her capacity as a researcher but as a teacher. “This is why I think the academy, as in higher education, is super important. We don’t just train the next generation. We also get to do research and sometimes we are the only canaries in the mine, so to speak.”

Where companies may be focussed on their bottom line, and politicians on the next vote, researchers can choose to place themselves in the service of the public. “I get to be among the people who ask, ‘Wait, what is going to be good for us in 20 years?’ That’s a true privilege for me, but it’s also a crucial role. Somebody has to try to figure out how we can make this all work better.”