News

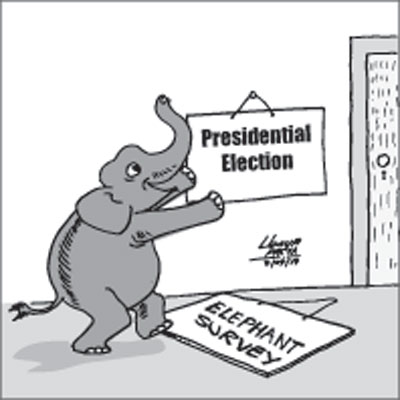

Elephant count method triggers debate on reliability

The islandwide elephant survey planned for September 13-14 is likely to be postponed due to bad weather in some parts of Sri Lanka, the Sunday Times learns.

The islandwide elephant survey planned for September 13-14 is likely to be postponed due to bad weather in some parts of Sri Lanka, the Sunday Times learns.

The Department of Wildlife Conservation (DWC) Director General Chandana Sooriyabandara, said the survey will “most probably’’ be postponed and an official announcement will be made tomorrow. The survey will be re-scheduled.

Mr. Sooriyabandara said that the water hole count method used in the 2011 elephant survey will be used, again. Usually done during the height of the dry season, teams will be at different points.

But when there are heavy rains, water will be available elsewhere and animals will not necessarily visit watering holes and the results may not be accurate, said Dr Lakshman Peiris, who is the DWC coordinator of the elephant survey 2019.

According to the DWC, 2,256 observation points will be used for the survey with 7,500 observers, including about 2000 volunteers.

The same counting points used in the 2011 survey will be used as it will provide data to compare population trends of elephants, said Mr Peiris.

Finding out the population trend and the distribution patterns of elephants inside national parks and elsewhere is another objective.

“The department needs the data to take management decisions,” Mr Sooriyabandara said defending another elephant survey after eight years following the first one. “It is a survey, not a census as some media reported,” Mr.Sooribandara said.

In a census, every member of the population is counted – something similar to the census of the human population. In the wild, it is very difficult to count every elephant. The survey will have an error component of plus and minus.

According to the 2011 elephant count, Sri Lanka has a population of 5,879 elephants.

Out of them, 3,285 were adults of both sexes and 1,487 were sub-adults. This also includes 731 juveniles, and 376 calves.

The 2011 survey also gathered data on tuskers, which made some activists to criticise the motives of the count.

About 6.5% of males are tuskers while sub-adult tuskers make up 7.7%. The juvenile tuskers represent 8.4%. Most elephants, or 67.19%, were found within the protected areas under the DWC, while 29.78% roam among forests managed by the Forest Department. The remaining 3.03% range in and around patches of small forest pockets near remote villages.

However, the water hole counting method is being criticised as unreliable.

At a reservoir, the same elephant herd may enter into a tank from different locations, causing a double-count.

A high density of animals also makes it difficult to count. Also, elephants sometimes visit watering holes at night making counting difficult.

Experts are needed to estimate the age, so identification by volunteers may be unreliable. For example, a survey usually puts a plus or minus error factor to the results and in the case of the 2011 survey, this had been high as 2,000.

Elephant expert Dr Prithviraj Fernando said there are many flaws in the water hole method where the number of elephants counted will be directly proportional to the number of observer points.

“If the 2019 survey uses the same number of points as last time, the result would probably be similar numbers. If the number of points are fewer, then the final total will be less.’’ However, Mr Sooriyabandara defended the water hole count method saying it is internationally accepted.

“Any ecological assessment method will have an error factor,” he said.“The count aims to compare the data with the 2011 survey to check trends in elephant populations and distribution.’’

Dr Fernando said there is no easy method.

Estimating by identifying individual animals from photos, or genetics and mark-recapture would give more reliable data, but is time consuming, expensive and cannot be done at a countrywide scale.

Elephant experts say that a much more useful survey would be to assess where the animals are and whether there are herds or only males and whether they are seasonal or resident.

Earlier this year, Dr Fernando published ‘the first evidence-based distribution map of Asian elephants in Sri Lanka’.

The study shows elephants are mostly found outside protected areas sharing the areas where humans live. In this study, from 2011 to 2015, the researchers divided Sri Lanka into 2,750 cells, each extending 25 square kilometres, which is the smallest known home range for wild elephants in Sri Lanka. Researchers visited people in a grid cell and asked if they have seen elephants in the area.

“Such surveys based on questionnaires could be done at a finer scale with a smaller grid in areas where there are conservation concerns such as edges of distribution, where development projects are planned. And conservation and management decisions can be made on such data,” Dr Fernando said. ’

The cost of the elephant count is estimated Rs 88 million and to be funded under the Ecosystem Conservation and Management Project, through a loan by the World Bank.