News

He left nothing unturned to uncover the truth

View(s):

By Kumudini Hettiarachchi

Dr. Lakshman Salgado in the old mortuary of the Colombo JMO’s Office

A pair of shoes in a polythene bag and a photograph of a colourful but pathetic-looking disabled aircraft sporting the monara on the tarmac!

The inextricable link between these two unrelated items is Dr. Merennege Sumitra Lakshman Salgado who strode the forensic medicine firmament like a colossus.

The shoes we see at the Institute of Forensic Medicine & Toxicology, Colombo, and the photograph of the Air Lanka Tristar (UL512) has been pulled out of the possessions Dr. Salgado treasured so much.

Dr. Salgado is no more and as we sit in his home down Melbourne Avenue in Bambalapitiya on Tuesday night chatting to his brother Raja, there is a sense of déjà vu. For we have been here on many an occasion earlier and there is an expectation that small-built Dr. Salgado may come down the stairs, with a little smile wreathing his lips and insist that we share a meal with him.

Today, September 8, Dr. Salgado would have celebrated his 89th birthday.

Even though he passed away on August 30 and was cremated last Sunday amidst a subdued crowd of students, peers and friends, many are certain that he will remain in the hearts and minds of his beloved countrymen and women, for he held steadfastly to all that was right, unbowed and undeterred by political or any other pressure, in the pursuit of ensuring that justice and fairplay would reign.

The shoes and the Tristar-photo are just two from the numerous cases where his meticulous work helped to clear fact from assumption and uncover the truth.

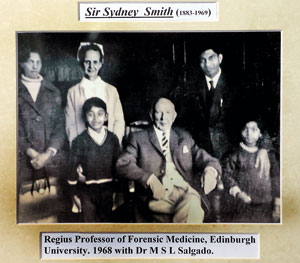

Dr. Lakshman Salgado and his family with the famous Sir Sydney Smith at the Edinburgh University, United Kingdom in 1968. Sir Sydney was a renowned forensic scientist and pathologist who had strong links with then Ceylon, for he had been flown down by the defence to reconstruct the crime during the case in which cricketer M. Sathasivam was accused of murdering his wife in 1951. Sathasivam was aquitted.

The shoes are those of 14-year-old Saman Kumara from Matugama who was abducted and killed in 1983. It is reported that his wealthy parents were given the ransom note demanding Rs. 250,000 after the hapless teenager had been killed and buried, in a murder case which shook the country.

The other, of course, is the Tristar bombing.

This is one of the famous cases associated with Dr. Salgado when he was Colombo’s Chief Judicial Medical Officer (JMO) from 1982-90, says two of his early post-graduate trainees, Dr. Senarath Colombage and Prof. Ananda Samarasekera.

After their rigorous training under Dr. Salgado who was a strict disciplinarian, Dr. Colombage went on to hold the post of Consultant JMO of the Colombo South Hospital from 1991-2008 and Prof. Samarasekera, former Chief JMO, Colombo.

“There was an explosion on the Tristar while passengers were boarding it at the Katunayake airport on May 3, 1986. It had arrived from England and was due to fly to the Maldives. As soon as Dr. Salgado was informed, he rushed to the blast-scene with his staff and trainees, with scant regard for his own safety,” recalls Dr. Colombage.

The images are still vivid for Dr. Colombage who was a trainee – there was chaos and confusion. Those were the days when there was no emergency disaster management protocol but Dr. Salgado was in his element, immediately taking stock of the situation. He got his team to collect the pieces of mortal remains and intact bodies, label them and seal them in separate bags as also the personal belongings of the victims and dispatch them to Colombo. The autopsies were conducted by him in Colombo in a systematic manner and identification carried out in days when there was no DNA testing. Dr. Salgado also inspected the aircraft’s interior, checking the damage. More than 20 died in the blast.

Dr. Senarath Colombage

Reiterating that an “essential” component in all medico-legal investigations is a visit to the scene as quickly as possible, Dr. Colombage says that Dr. Salgado ingrained this principle in the trainees’ minds and set up a 24-hour on-call roster to respond to emergencies.

Prof. Samarasekera expands on other important forensic investigations that Dr. Salgado conducted including the hand-grenade explosion in Parliament, the assassination of politician Vijaya Kumaratunga, the killing of ruggerite Tony Martin and the homicide-suicide of a prominent couple in the garment industry in Moratuwa.

Adding some details seared into his memory with regard to the Tristar blast, he says that there was a lot of controversy where the bomb was – did a passenger carry it on board or was it elsewhere? Dr. Salgado’s work along with the Government Analyst’s findings determined that it had been in the cargo section.

Prof. Ananda Samarasekera. Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

In the homicide-suicide of the Moratuwa couple in their bedroom, the popular belief was that the husband had killed his wife and killed himself, but Dr. Salgado’s probe indicated otherwise. It had been the wife who killed the husband and then took her own life.

Prof. Samarasekera re-visits the bomb blast in Parliament in 1987 and explains that there were contradictory views whether a firearm had been fired, as a click had been heard, before the hand-grenade explosion. This incident in which Members of Parliament such as Keerthi Abeywickrema was killed and Lalith Athulathmudali was injured, sent shock waves across the country. It had been Dr. Salgado who had determined that the click heard just before the explosion was a door being opened and not a shot being fired.

After the autopsy on the body of a parliamentary clerk, Norbert Senadeera, Dr. Salgado had given the cause of death as “fatal injuries to the brain……by shrapnel from an explosive device”. So it had been a hand-grenade.

With emotion, Prof. Samarasekera says how he learned “a lot” from Dr. Salgado, dealing in-depth on his mentor’s focus on all fields connected to forensic medicine which essentially includes ‘clinical forensic medicine’ which deals with the ‘living’ and involves examination of a victim or a perpetrator for medico-legal issues and ‘forensic pathology’ which deals with the ‘dead’.

Currently, about 40 specialists in forensic medicine (JMOs) work for the Health Ministry in major state hospitals across the country and about 20 for the Higher Education Ministry in the medical faculties.

“Dr. Salgado created a special interest in histopathology, setting up a laboratory for this work where sections of dead bodies could be studied under a microscope to come up with scientific findings,” he says, citing how it helps to determine whether an injury had been caused before or after death. The pioneer that Dr. Salgado was, he had also developed the field of radiology in forensic medicine by setting up a mini-lab at the Colombo JMO’s Office, whereas earlier everything had to be sent to the Government Analyst’s Department.

Some of the major changes to the system that he introduced included putting a stop to minor staff being the “cutters” of dead bodies, with the Health Ministry issuing a circular on the insistence of Dr. Salgado that it was the duty of the JMO. This was while he showed all allied fields how postmortems including dissection of bodies were conducted, bringing into the mortuary judges, lawyers and police.

The battered Tristar on the tarmac

“Of course, when we were in training, we hated him as he was a hard taskmaster and stickler to protocols,” smiles Prof. Samarasekera as Dr. Colombage joins in to give details of how he devoted his life for the betterment of the field.

In the early 1980s when there were only a handful of medico-legal specialists in the country, he along with a few others had convinced the management of the Post-graduate Institute of Medicine (PGIM) to set up a Board of Study in Forensic Medicine to train specialist JMOs, he says, adding that now they are spread across the country providing a quality service and in the universities teaching undergraduates and post-graduates.

Dr. Colombage explains that as it takes about 4-5 years for a doctor to become a consultant, until there were adequate numbers to serve in all parts of the country, Dr. Salgado had taken steps to upgrade the knowledge and skills of District Medical Officers (DMOs) and Medical Officers (MOs) in-charge of peripheral hospitals who were performing the bulk of the medico-legal work in those areas. He had organized a WHO-sponsored one-month in-service training programme for them at the Colombo JMO’s office, with the expertise of British Forensic Pathologist Prof. Bernard Knight.

“Initially, as there weren’t many trainers or specialists in allied fields to provide expert knowledge for forensic medicine trainees on toxicology, firearms and bombs, Dr. Salgado made use of his personal contacts to rope in outside experts for the postgraduate teaching programme,” he says, pointing out that for the one-year overseas training in a recognized unit, he once again made use of his contacts with renowned experts such as Prof. Knight, Prof. J.M. Cameron, Prof. David Bowen, Prof. Stephen Cordner and Prof. Tom Marshall to find slots for them at centres of excellence. Of these, Australia’s Victorian Institute of Forensic Medicine alone has trained over 20 and still accommodates a trainee each year.

As an expert witness, meanwhile, he was held in high esteem by the judiciary and both the prosecution and the defence lawyers relied heavily on his unbiased, unwavering and scientifically formulated evidence, says Dr. Colombage.

There were also many other things, both locally and internationally, very close to his heart. They included the Medico-Legal Society of Sri Lanka (MLS) of which he was President from 1984-1986; the Sri Lanka Medical Library of which he was President in 1994/95; the College of Forensic Pathologists of Sri Lanka of which he was a founder member and later President in 2011; and also the Indo-Pacific Association of Law, Medicine and Science (INPALMS) which was established by him together with Prof. Chao T. Cheng of Singapore. Dr. Salgado was its second President from 1992-1998 and Congress Chairman when its second congress was held.

Although he appeared to be rigid during official engagements and had his own way of accomplishing things, he would be the first to render help when someone under him needed it, says Dr. Colombage.

For people whose paths crossed those of this doyen of forensic medicine, an enduring memory would be how he never-ever bowed to pressure of any kind in the discharge of his duties, setting a shining example to his juniors. Truth without fear or favour was his motto, while taking a tough stance against police brutality and torture.

|

Dr. Lakshman Salgado The making of a ‘rebel’ The middle son among three boys, Punchi Aiya born in Gintota, Galle, was quite rebellious as a teenager, smiles his Malli, Dr. Raja Salgado. Explaining the family circumstances, Raja who is a Geriatrician in Australia, says that whether at Royal College, Colombo, or at home everyone kept comparing Lakshman to their eldest brother, Ranji, who was dubbed brilliant. Just one year younger than Ranji, Lakshman would be told: “You are not like him. He’s a clever boy.” So Lakshman became rebellious and made his mark by causing trouble, laughs Raja, who believes that living in the shadow of his brother also toughened him (Lakshman). The medical entrance he flunked twice and wanted to go to Christian College in Madras, India but within a week was back at home. There was only one more shy left for him to enter the medical faculty and it was then that he decided to buckle down and study, coming under the gentle influence of teacher and mentor M.K.M. Pannikar at Ananda College. The rest is history. As a JMO, he was 100% honest and fearless, uncaring about the personal consequences of keeping his integrity, says Raja, recalling an incident when Lakshman was Galle JMO in the 1970s. He wanted the body of a man from Walasmulla who had died in police custody to be brought to Galle for the postmortem, but the police were reluctant to do so. The police had informed the Inspector General of Police (IGP) who, in turn, had told Justice Minister Felix Dias Bandaranaike, a powerful force in the then government. “Felix had rung up Lakshman and told him to go to Walasmulla for the postmortem, but he flatly refused and Felix was very angry,” he says, recalling many such instances where Podi Aiya had stood up to top leaders, in his line of duty. | |