The bold and the intangible; an artist unveiled

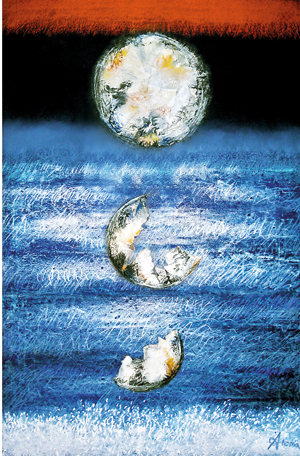

A long creative journey: The young Anoma, and left and bottom left, some of her work as depicted in the book

In January this year, Anoma Wijewardene found herself under a table in Singapore. In the city to meet with Pristone, the printer of her new monograph ‘Anoma’, she was on pins as she waited to ensure that the book’s pages would be as colour accurate as possible. “Most of the photographers and artists who visit us often get bored in between sheet checks,” Pristone’s director Zhi Yuan Lee would later recall. “Anoma entertained herself by painting and sleeping under the table. What an enjoyable individual, I thought…we ate loads of duck and quacked lame jokes.”

It is an anecdote that perfectly captures one of Sri Lanka’s most celebrated artists – both the seriousness of purpose that has seen her through the seven years of work on her eponymous monograph, and a stubborn streak of irreverence that surfaces every now and again, as if she could not resist undercutting her own gravity. The monograph was launched in London in March, timed to coincide with International Women’s Day. Its long awaited release in Sri Lanka was delayed but Monday, September 9 will mark its debut here.

Right now there are piles of books everywhere – and several are stacked on the edge of Anoma’s dining table. It has consumed her days of late. “I haven’t been able to paint,” she says ruefully, alluding to all the pre-launch logistics that need to be attended to. The sensation of being deprived of her paints and canvas is almost physical. “Painting is my breath,” she says, adding “I don’t feel right, I almost don’t feel alive when I am not painting.”

It is evident that she has put a lot on hold to produce ‘Anoma’, a celebration of her life’s work. She trusted the project’s art direction to Chris Sanderson, CEO and co-founder of The Future Laboratory, and the design to Micha Weidmann and his team, the latter having produced volumes for Christie’s, Google, Tate Modern and Condé Nast Publishing. Together they collected and laid out her paintings, photographs and images of her installations, sculptures and multi-media work, placing them in chronological order and painstakingly labelling each so that a reader might readily situate each piece.

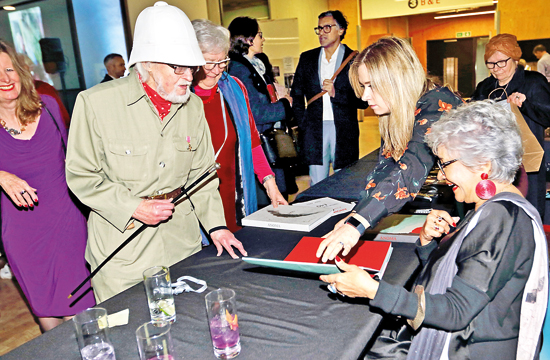

Anoma, at right, autographing books at the launch in London

Anoma did not set out to construct her legacy, and yet the book does precisely this, in that it allows the artist herself to articulate her intentions, her process and her inspiration. She writes of her approach: ‘It is a long, iterative, torturous journey towards perfection. In that journey of pain, anxiety and transcendence, I come alive.’ Now, she tells the Sunday Times that she wanted people to understand how much work goes into the creation of a single painting, involving months of writing and reading, thinking and dreaming before her vision is realised.

One year away from 70, Anoma finds herself looking back on the woman she once was to the kind of artist she has become. Particularly to her mind, it is not a clean trajectory. She admits readily to piercing self-doubt and to finding “something to regret every day,” even as she recognizes simultaneously that the years have been generous, bringing with them clarity and ambition, crystallising for her what she wants and what she will stand for. At the heart of it all is a creative vision that has been decades in the making.

Looking through her Monograph, Anoma sees clearly that her numerous exhibitions fall neatly into three broad categories. There are those such as ‘Flight’ (2004), ‘Quest’ (2006) and 2019’s ‘Kintsugi’ produced for the 58th Venice Biennale, which all explore themes of faith, diversity and reconciliation (“finding harmony in our fractured world”) while a second set, which include exhibitions such as ‘Solitude’ (2002) and ‘Transformation’ (2008), look inward and focus on personal transformation.

Looking through her Monograph, Anoma sees clearly that her numerous exhibitions fall neatly into three broad categories. There are those such as ‘Flight’ (2004), ‘Quest’ (2006) and 2019’s ‘Kintsugi’ produced for the 58th Venice Biennale, which all explore themes of faith, diversity and reconciliation (“finding harmony in our fractured world”) while a second set, which include exhibitions such as ‘Solitude’ (2002) and ‘Transformation’ (2008), look inward and focus on personal transformation.

The third category is fuelled by her grim conviction that the world is teetering on the edge of catastrophe as climate change tightens its grip on the planet. This collection includes the likes of ‘Deliverance’, an exhibition inspired by the poetry of Ramya Jirasinghe which Anoma would stage multiple times beginning in 2009, and 2016’s ‘Earthlines’, which was conceptualised as a response to the historic 2015 UN climate change conference in Paris and combined paintings with delicate glass sculptures.

The monograph is structured around these visuals and five essays. Beginning with a meditation by the respected scholar Gananath Obeyesekere on the Buddhist thought in Anoma’s work, they become increasingly personal until the book ends in a piece titled ‘Genesis: The Formative Years’ by Jane Rapley OBE, who served for 17 years as Dean of Fashion and Textiles at Anoma’s alma mater Central Saint Martins, where she helped launch designers such as Alexander McQueen, Matthew Williamson and Stella McCartney.

In his essay, Jana Manuelpillai, a prominent collector and dealer in Indian, Sri Lankan and Pakistani modern and contemporary art, casts Anoma as a romantic in search of the sublime. Respected art critic Rosalyn D’Mello says of Anoma’s work that ‘She is using the vehicle of her own art to propound a way of seeing man and nature not as binaries in opposition to each other, but as complementary, symbiotic modes of being that must sustain and fertilise each other…’

Anoma Wije-wardene: Pushing the boundaries

Anchored in these broad concerns, Anoma herself embraces a kind of vigilance that ensures she is never too comfortable. She is her own guardian, determined to keep pushing the boundaries of her own capabilities. Of course this comes at a price. The self-doubt that drives her can be almost physically painful. “It hurts the heart,” she says frankly. But it is a price Anoma has always been more than willing to pay. As a result her work is bold, demanding your attention, yet simultaneously ephemeral; each canvas a window into something intangible.

The monograph attempts to show us how Anoma arrived at this moment. In his essay, Richard Simon attempts to place Anoma in her context. He begins by noting that when Anoma returned to Sri Lanka after nearly three decades in the UK, she was ‘reconnecting with a family history that was not merely private but also public.’

Among her relatives, Anoma counts political heavyweights, notable southern entrepreneurs, a media magnate and a member of the ’43 Group. Her father Ray Wijewardene was often hailed as a renaissance man, who pursued his passions for science, engineering, innovation, education and research with a kind of relentless focus; her mother Seela, was a gifted piano player and consummate hostess, who could step in to crew for Ray when he sailed his yacht and needed little coaxing to brave a flight in one of the small aircraft that he self-assembled.

To a large degree, Anoma was disconnected from this network when she left Sri Lanka at the age of 16 to pursue her studies in India, and then again when she moved to the UK. Jane writes of the wonder and strain of that time, as Anoma studied design and began to make a name for herself, creating signature fabrics that would catch the eye of, among others,Loulou de la Falaise at Yves Saint Laurent, Jean-Paul Gaultier at Cacharel and Pierre Cardin himself.

To a large degree, Anoma was disconnected from this network when she left Sri Lanka at the age of 16 to pursue her studies in India, and then again when she moved to the UK. Jane writes of the wonder and strain of that time, as Anoma studied design and began to make a name for herself, creating signature fabrics that would catch the eye of, among others,Loulou de la Falaise at Yves Saint Laurent, Jean-Paul Gaultier at Cacharel and Pierre Cardin himself.

It is also around this time that Anoma met and married David, the third Earl Beatty. The two would separate after over a decade of marriage, and Anoma would return to Sri Lanka where she realised her long felt dream of becoming an artist who answered to no one but herself.

While it is clear that between her lineage and her marriage, Anoma could have leveraged her name to great effect, she has chosen always to simply sign her work with her first name, determined that it will stand or fall on its own merit.

Combined with her travels and the twists of her own life, this determination has left Anoma in many ways an outsider and though she may have struggled with that as a young woman, she has always recognized that it is a useful thing for a creative to be. “Especially to paint, you have to see the truth,” she tells me. “I have to be a truth seeker because I have to be a truth teller. To be a truth seeker, you have to be kind of an outsider. If you are inside, you can’t see.”

With the extraordinary force of her conviction, and her willingness to report back to us of journeys that have taken her deep into her own being, and beyond into the world, Anoma is an adventurer in the truest sense. And it is Gananath Obeyesekere, who in his essay, elaborates on what that means for us, for those who stand in front of her work and find ourselves compelled to feel, to think, to care.

He writes: ‘Her parents chose her name rightly. Anomā was the river the Buddha has to cross after he left home for the homeless life, soon to become the Fully-Awakened One. Each of us, in our own way, irrespective of our religious upbringing, has to cross that metaphorical river if we hope to intuit a sense of a world outside commonplace everyday life. As Anoma is telling us, there is something out there we cannot afford to miss.’

‘Anoma’ the monograph, is sponsored by Colombo No.7 Gin

The book is priced at Rs.12,500 and will be available at Urban Island, Dharmapala Mawatha, Colombo 7 and at Barefoot Bookshop, Galle Road, Colombo 3 from September 10.