Appendicitis: To operate or not to operate?

After a long and celebrated reign Queen Victoria of England died in 1901. Her oldest son Edward was due to be crowned King on June 16, 1902. Two weeks before the great event, he began to get episodic pain in his abdomen, which then became constant and severe. The most eminent physicians in the land gathered around him, and when the Prince began to deteriorate, they did what physicians have done from time immemorial; they sent for a surgeon.

After a long and celebrated reign Queen Victoria of England died in 1901. Her oldest son Edward was due to be crowned King on June 16, 1902. Two weeks before the great event, he began to get episodic pain in his abdomen, which then became constant and severe. The most eminent physicians in the land gathered around him, and when the Prince began to deteriorate, they did what physicians have done from time immemorial; they sent for a surgeon.

The most distinguished surgeon in England at the time was Sir Frederick Treves, and summoned to the royal bedside, Treves diagnosed an appendix abscess and advised immediate operation.The Windsors have a reputation for being phlegmatic, but not bright. The Prince, demurred, claiming “my people would expect me to attend the coronation.” To this Treves is said to have replied, “Then sir, you will go as a corpse.” The prince then changed his mind. Treves drained his appendix abscess in a room in Buckingham Palace under an ether anaesthetic. The coronation was delayed at vast expense, but he was eventually crowned in August 1902, and as Edward the VII went on to rule for seven years. With his appendix! Treves was lavished with Royal honours, and became one of the most famous men in England.

The last half of Victoria’s reign, and that of her oldest son marked what came to be known as La Belle Epoque, a period of extraordinary wealth, innovation and creativity. On the medical side, Pasteur laid the groundwork for the germ theory of disease allowing Lister to make Operative Surgery safe for patients. Anaesthesia was brought out of the fairgrounds into hospitals; operating theatres were designed using Listerian technologies, and Surgery transitioned from uncertain craft to a thoughtful science.

It is likely that appendicitis has been an affliction of mankind for millennia. But the precise cause of abscess formation in the lower abdomen was thought to be a disease of the caecum- what the French called “typhlitis”. In 1886 in a masterly presentation in Boston, the pathologist Reginald Fitz described the evolution of appendicitis, and recommended to surgeons that early removal of the appendix would prevent the lethal complications of the disease.

Supported by the increasing availability of anaesthesia, American surgeons took this advice and across the country appendixes were sacrificed on altars of both necessity as well as expediency. The saying “there are two types of appendicitis, acute suppurative, and chronic remunerative” became fashionable to describe adventurous surgeons. Surprisingly many surgeons in England and France were less enthusiastic, and preferred to wait until an abscess formed following appendicitis and then draining the abscesses and sometimes removing the appendix. By 1906 Treves himself had operated on over a thousand patients with appendicitis, but he did not believe in early operation. When his young daughter developed appendicitis, Treves delayed an operation leading to her death.

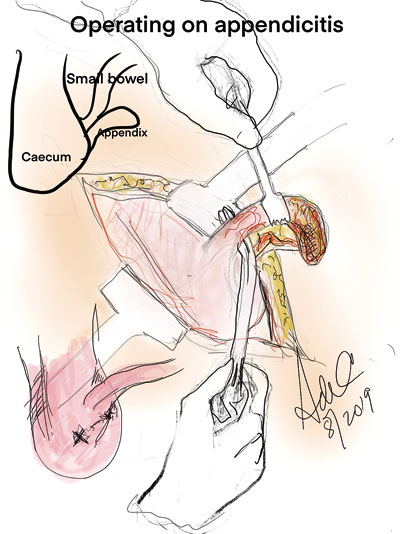

Eventually the notion of early surgery for appendicitis was widely adopted. Over the last 20 years keyhole surgery has become standardized, and young doctors the world over use expertise in laparoscopic appendicectomy as the foundation for the development of their surgical technique. Serious morbidity is uncommon, and death rare.

Well, is that the end of it? Perhaps not quite.

Why do people develop appendicitis? Surprisingly the answer is unclear.

So, what do we know about the demographics of appendicitis? Where it has been studied, the condition may affect anyone at any age. The highest incidence is in the second decade. Males suffer from appendicitis slightly more than females, and in Europe and North America, there is a seasonal variation, it being more common in the summer and autumn. Twin studies have been striking, suggesting that up to 30% of all cases of appendicitis may have genetic associations.The incidence of appendicitis is about 30/100,000/ per annum, 30% of which are perforated, giving a lifetime risk of around 9% in western populations.

Back to the question “Why do people get appendicitis?” An explanation given by surgeons over the years is that something blocking the opening of the appendix into the caecum may allow bacteria to overgrow, inflame and perforate the appendix. The commonest cause is of a faecalith, a hard lump of faeces, sometimes calcified, that blocks the appendix. Other things that block the appendix as well, like a piece of bone, lead shot, seeds or even parasites reinforce this view. The appendix itself may be involved in its own disease processes eg cancer, infections eg. measles and other inflammatory conditions. But the great majority of cases have none of these things. They seem to just happen.

It has also been known that some cases of appendicitis seem to resolve, and others to resolve with the use of antibiotics. This has sparked intense research interest, as if antibiotics can be shown to “cure” appendicitis, a different treatment pathway, outside the surgical pathway of early operation may emerge. Initial research tended to support the proposition that antibiotics may indeed cause resolution of early appendicitis. Many different antibiotic regimes seemed to work equally well. Over the last two years many of these studies have been pooled together(meta-analysis) and a half dozen are now available. It must be emphasized that these studies looked at early appendicitis, and where there was any likelihood of perforation or peritonitis these patients were operated on immediately.

What these analyses seem to be telling us is:

- 75% of cases of early appendicitis may respond to antibiotic treatments

- Almost all antibiotic regimes from the simplest to the most powerful, seem to work equally well

- In a majority of cases appendicitis may not be progressive to perforation, and perforating appendicitis may be a separate entity.

- 100 % of cases are cured by appendicectomy

- Of those that respond to antibiotics a proportion will recur requiring further treatment.This group may be 10-20%.

Conclusions from these analyses suggested that while an effect of antibiotics was likely, this was of insufficient magnitude to recommend a change in protocol. Early appendicectomy also deals with the small number of cases of appendix tumours (0.5%), that non-intervention may miss.

Conclusions from these analyses suggested that while an effect of antibiotics was likely, this was of insufficient magnitude to recommend a change in protocol. Early appendicectomy also deals with the small number of cases of appendix tumours (0.5%), that non-intervention may miss.

A recent further interesting study from Korea, has shown that if patients with early appendicitis are randomized into a treatment arm (antibiotics only) and an observation only arm, a similar number from each group resolve, and a similar number progress to appendicectomy. This will have to be confirmed with other studies, but raises the tantalizing possibility that a majority of patients with early appendicitis may well resolve with or without antibiotics rather than progress to perforation and peritonitis.

One of the clear messages from some of this work, is that early appendicitis, is not an emergency and can be managed in the light of day. Perforation or peritonitis is managed with urgent operation to save life.

This underlies the necessity for diagnostic precision and the differentiation of uncomplicated appendicitis from complicated or perforated appendicitis. How is this done?

The very basis of western Medicine emphasizes history and physical examination. It has long been known and worked out statistically that certain signs and symptoms are associated with a particular diagnosis. Appendicitis is a good example of these systems at work, and have allowed different Scoring algorithms to be worked out. The Alvarado Score for appendicitis is one of them.

Alvarado score — The Alvarado score (also called the MANTRELS score) is a 10-point score derived from eight components: (Modified)

- Mild generalised abdominal pain (1 point)

- Anorexia (loss of appetite) (1 point)

- Nausea/vomiting (1 point)

- Tenderness in the right lower abdomen (2 points)

- Rebound tenderness (suggesting localised peritonitis) in the right iliac fossa (1 point)

- Elevated temperature >37.5°C (1 point)

- Elevated white blood cells in blood (2 points)

- Shift of the white blood cellcount( where more cells showing infection become apparent) (1 point)

So clearly an A score of 3 or less will not need surgical review. A score between 3 and 7 may suggest further diagnostic steps. This is where imaging is used and where surgical opinion may be sought. Without imaging at this stage and proceeding to operation (look and see rather than wait and see) a negative appendicectomy rate (where an operation is performed and the appendix is normal) may be as high as 20%. Good imaging should bring the negative appendicectomy rate to 5% or less, and is what good practice demands.

Abdominal ultrasound is the cheapest and safest imaging modality. It is quite sensitive (where a positive result strongly supports the diagnosis of appendicitis) but not very specific (a negative result does not outrule appendicitis), and rather dependent on who is doing the test. An abdominal CT scan is both very sensitive and specific, and is increasingly used routinely particularly in North America. Someone with an Alvarado score greater than 7 may proceed directly for surgical review and operation, though increasingly these patients will have CT scans as well.

The place of imaging is particularly important in some clinical situations, children under 5, and pregnant women. In these situations diagnostic precision has to be achieved with urgency, and imaging including CT scan, US and even MRI may have a role.

These are often difficult situations requiring specialist expertise across several areas to bring successful resolution.

Surgery and anaesthesia are not risk free. There may be a 5% risk of complications from operation, and about a 2% lifetime risk of intestinal obstruction.

But none of this tells us why appendicitis occurs. The science of metagenomics gives us an insight into the organisms that populate the human intestine. This combined with the use of sophisticated microscopy shows that a high proportion of cases of perforated appendicitis are associated with invasion of the appendicular wall- but by organisms not normally seen in the bowel, but in the mouth (fusiformis). These organisms are sensitive to most antibiotics, and may relate to some of the studies mentioned earlier.

Good research answers some questions, but raises others. Surgery, the most practical of crafts, remains the handmaiden of good science.

Felix qui potuit rerum cognoscere causas

Happy is he who has learned the causes of things

Virgil. Georgics, 29 BC.

( The writer is Prof. of Surgery, James

Cook University,

Cairns , Australia)