News

Major efforts to curb worrisome maternal suicides

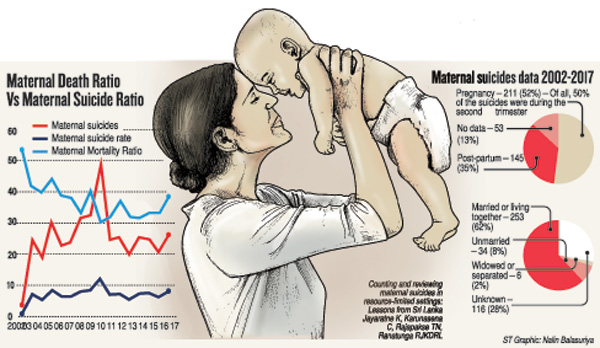

Sri Lanka has received many an accolade for its low maternal mortality rate (MMR) but there is rising concern over maternal suicides which are pushing up these numbers.

Dr. Mohamed Rishard

Taking serious note of this disturbing trend, there is a concerted multi-pronged and multidisciplinary effort not only to find out what has led these mothers to take their own lives but also how such incidents can be prevented, the Sunday Times learns.

With mental illness being strongly linked to these maternal suicides, experts underline the need to “catch” such illness early, at the first booking date or when expectant mothers register initially at the grassroot level.

Then these vulnerable mothers can be screened and supported or treated if necessary, with the health staff being extra-vigilant about them, they say.

The different groups which are working tirelessly to bring about zero-deaths among mothers are the Health Ministry’s Family Health Bureau (FHB), the Community Physicians, the Medical Officers of Health (MOHs) along with the grassroot-level health workers as well as the Sri Lanka College of Psychiatrists and the Consultant Obstetricians & Gynaecologists.

Reiterating that maternal suicides are a “significant” cause of maternal deaths, FHB’s National Programme Manager for Maternal and Child Morbidity & Mortality Surveillance, Dr. Kapila Jayaratne defines what ‘maternal suicides’ are. “They are all suicidal deaths of women in the reproductive age group (15-49 years) during pregnancy and until one year after the conclusion of the pregnancy.”

Consultant Psychiatrist Dr. Chathurie Suraweera who is attached to the Faculty of Medicine, Colombo, and the National Hospital of Sri Lanka says that ‘suicide’ is the act of killing oneself, while ‘deliberate self-harm’ is the intentional act of causing physical injury to oneself without wanting to die.

A ‘maternal death’ is a death that follows a registrable live-birth or stillbirth at or more than 24 weeks of gestation (the development period of a foetus until birth), she says quoting the World Health Organization (WHO). Such a death can occur in pregnancy, within 42 days of delivery (early) or after 42 days to 1 year (late) of delivery.

Thereafter, she focuses on the three types of maternal deaths.

- Direct – due to haemorrhage (excessive bleeding)

- Indirect – due to cardiac or psychiatric causes

- Coincidental – due to accidents etc

“Under ‘indirect deaths’ due to psychiatric causes fall suicides; those related to psychoactive substances; and others (homicide and adverse drug reactions),” says Dr. Suraweera.

The RED Book

Looking back at how Sri Lanka has stymied a rising trend in general suicides from having the second highest suicide rate in the world at 47 per 100,000 in 1996 to 14.6 per 100,000 currently, she expresses serious concerns over maternal suicides. “This is an emerging threat to maternal well-being.”

The MMR was 39 per 100,000 live births in 2017 and is stable in the range of 30 to 40 per 100,000 live births from 2006 to 2017. However, there is a notable rise in the maternal suicide rate which was 6.3 per 100,000 live births until 2016. This has increased to 8.3 and 11.7 per 100,000 live births in 2017 and 2018, the Sunday Times understands.

Stressing that tragically a mother’s death impacts on the children, family and community, Dr. Jayaratne explains that the Health Ministry has introduced a field investigation using the Psychological Autopsy Tool for Maternal Suicides (PAMS) from 2016. “This has enabled the notification of such a death by the MOH of the relevant area to the FHB, the Regional Director of Health Services and also the Consultant Psychiatrist of the nearest hospital,” he adds.

He says that those who are part of the ‘field maternal suicide investigation’ are a Consultant Psychiatrist, Provincial Consultant Community Physician, the MOH, the Public Health Nursing Sister (PHNS) and the Public Health Midwife (PHM).

Justifiably proud of the fact that Sri Lanka is the only country in the world which has introduced PAMS to find the cause of maternal suicides which would help prevent such incidents in the future, Dr. Jayaratne says that the investigation takes an in-depth look at the profile of the deceased mother.

The investigation is expected to be done as soon as possible and completed in 14 days of the maternal suicide, with family members, close associates, friends and even the General Practitioner (GP) the deceased may have gone to, being interviewed to try and fathom scientifically what led to the maternal suicide, says Dr. Jayaratne.

“We also introduced in 2014 the RED Book Strategy,” he says, explaining that when the PHM is doing her rounds at ground level, if she comes across a mother who is vulnerable, she will get back to the MOH office and make an entry in the RED Book, which stands for ‘Register of Eligible women in Danger’. Then the MOH and his team will immediately respond by visiting this vulnerable mother with a case-by-case targeted intervention, securing the assistance of sectors other than health as well, when needed.

Dr. Kapila Jayaratne

Dr. Chathurie Suraweera

The PAMS data for 2016, meanwhile, have uncovered many aspects:

- The suicides appeared to have had prior planning by about 31% of the mothers, with around 21% making prior attempts.

- Of those who died in the suicide attempts, around 36% appeared to have been depressed, while around 15% had a family history of suicide and around 21% had a relative who had attempted suicide.

- The suicides had taken place in their home surroundings.

- Many suicides were associated with inter-personal conflict.

- 1 in 5 women suffers from some sort of a mental health problem during the perinatal (at or around the time of birth of the baby) period.

- 10-15% of women in the perinatal period suffer from depression.

- The prevalence of post-partum blues may be as high as 85%.

- 1-2 per 1,000 suffer from post-partum psychosis.

- Maternal or baby blues – Mood lability (exaggerated changes in mood), tearfulness, anxiety or irritability, with the symptoms peaking on the 4th or 5th day after delivery and lasting a few hours or a few days. The blues go away in a few weeks but sometimes could be a harbinger of a bigger illness, especially in those who have a history of depression.

- Post-partum depression – Usually comes later than baby blues and psychosis, about two weeks after the delivery of the baby. The symptoms include a significant low mood; not being able to carry on the usual work; not being interested in pleasurable activities; sleep and appetite changes; and excessive worry about the baby and his/her health. Post-partum depression can lead to suicidal ideations (thoughts of ending life), self-harm and also harm to the baby.

- Post-partum psychosis – this is a severe form of psychiatric illness with the symptoms including abnormal behaviour; abnormal beliefs especially pertaining to the baby or herself; and smiling or muttering to herself. Post-partum psychosis can also lead to suicidal ideations, self-harm and harm to the baby.

Meanwhile, Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist Dr. Mohamed Rishard of the De Soysa Hospital for Women, Colombo, echoes the need to look more closely at perinatal mental health.

Quoting many scientific publications including ‘Perinatal mental illness: A public health priority’ (Sri Lanka Journal of Psychiatry, June 2018) and ‘Reducing maternal suicide in Sri Lanka: closing the gap’ (Sri Lanka Journal of Psychiatry, June 2016), he reiterates that Sri Lanka should strengthen the existing screening and referral systems for vulnerable mothers.

“In the hospital setting it is difficult to pick up depressed mothers, as the workload is heavy, the staff is not trained in this direction and resources are low,” he says.

He explains that another concern is that whenever in the hospital setting they do identify a mother who needs perinatal mental health services, her family is usually in a hurry to take her home, disregarding medical advice. The family believes that when the mother and baby go home

“everything will be alright” but relatives do not know how to support such a mother.

Commending the midwives for the good job that they are performing at grassroot level, Dr. Rishard says that they should be strengthened to screen mothers for mental illness, after which they can refer them to the MOH and the closest hospital.

Recognizing the emerging threat of suicides and perinatal mental illness, early recognition and prompt management have become a priority in many countries which should also be a priority in Sri Lanka, say the experts, adding that “we are getting there”.

| Booking stage a good time to screen for mental illness | |

| Let’s try and catch mental illness in expectant mothers early as detection and treatment of perinatal mental illness are important as also strengthening of existing services to curb maternal suicides.This is the strong plea going out from experts who point out that even though the best outcome would be from screening women at the pre-conception (before they conceive) stage, if they can be identified at least at the ‘booking stage’ it would be very good. “This is what we are working towards to screen them for mental illness as we do for other physical illnesses,” says Dr. Chathurie Suraweera, explaining that the ‘booking stage’ is when they book a visit with the MOH. Giving the global trend, she says that there is screening, followed by dedicated perinatal mental health services and mother-baby units. During screening when such vulnerable mothers are identified, they are monitored, pre-conception counselling done and multi-disciplinary care planned during the pregnancy and post-partum period. The mothers who are severely affected are kept in a dedicated ‘mother-baby unit’ without separating the baby from the mother. According to this Consultant Psychiatrist, the challenges that Sri Lanka should overcome are: · With nurses whose duty hours are fully occupied by maternal care, hardly able to devote time to psychiatric patients – there is a need for a sub-speciality or those having a special interest in this to be identified. · If the hospitals cannot have mother-baby units, maybe a few beds should be dedicated in the maternal wards for those with perinatal psychiatric issues. · More awareness is needed on mental health issues among medical professionals, the community and the media. This would help to overcome stigma, cultural myths surrounding childbirth and fears on taking the necessary medications for mental illness. |