Taking on the Mahaweli in a rudderless bamboo raft

The fragile bamboo raft that braved the Mahaweli.(September 1964)

Even as a seven-year-old I regarded the KonTiki expedition of the Norwegian anthropologist-historian Thor Heyerdahl and his crew sailing in 1947 from the South American coast to an island near Tahiti as an inspirational event as did so many of my generation.

Scrutinising the original raft at the Maritime Kon Tiki Museum, in Oslo, Norway in 1967, 20 years after the event, I was astonished that such a tiny, fragile craft could overcome the Pacific ocean’s mighty waves.

Closer home, though not half as dramatic, was Richard Brook’s (1798-1834), attempts to navigate the Mahaweli Ganga upstream from Mutur, Kodiyar Bay, Trincomalee to Kandy.

Brook, however, was merely following the directives of his commanding officer, Surveyor General John Wilson to explore the navigability of the river.

By March 1832, Brook accomplished his goal. Abandoning the boat at Aluthnuwara he then rode 25 miles and when his horse slipped off a cliff, completed the journey to Kandy on foot. By 1833, Brook’s report ‘Extracts from the journal to Explore the Mahaweli Ganga undertaken by Direction of the Ceylon Government’ was published by the Wesleyan Mission Press. This Octavo publication is a rare antiquarian collector’s item.

By 1960 more than a dozen downstream crossings of the Mahaweli to Mutur were undertaken. By international standards, this feat was a cakewalk. The Mahaweli is an inconsequential stream of 205 miles. No comparison to those mighty rivers in Africa, America and Asia thousands of miles long where danger lurks at every bend in the river -if one escapes negotiating the raging rapids, a possible attack either from wild animals or overtly aggressive tribes would be the norm.

Most Mahaweli excursions, in comparison, were well planned and equipped. The sailing craft were often made of timber or fibreglass to withstand the rigours of the journey. These included canvas tents, canned foodstuffs, water for drinking, fuel for cooking, waterproof clothing, ropes and tackle – every item vital to deal with any unforeseen accidents.

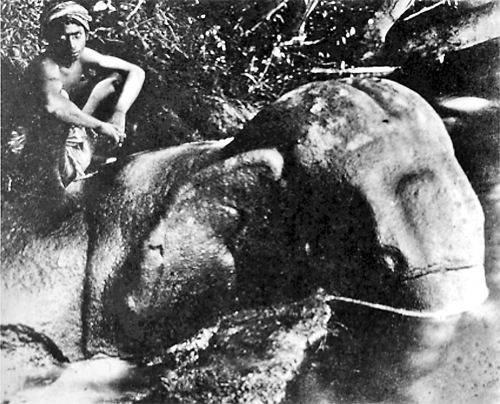

Boy astride the Rock Cut Elephant.(H.C.P.Bell,1898).Reproduced in the article by H.C.P.Bell -The ”Gal Aliya“or “Rock Elephant” at Katupilana, Tamankaduwa (1917).

But all said, the river’s waterflow was unpredictable; often at the height of the drought period the river runs shallow, drifting sand banks block the way, making navigability almost impossible. Many a failed expedition had to summon help and haul the boat up the steep river banks and transport both men and materials by tractor to the main road at huge expense.

In 1964, our solution to raft down the Mahaweli was simple and cheap. The raft was constructed of bamboo poles and floats of banana trunks lashed together with coir rope

Unfortunately, there was no provision for a rudder, only two oars to steer our way past the rapids and sand banks. We travelled light not carrying tents with the idea of sleeping in the open. Thus equipment, clothing and food stores were kept to a minimum.

Working within a tight budget, costs were negligible– we could always jettison the raft anywhere along the route and swim our way out of trouble- or that’s what we envisaged.

This seemingly ill planned and harebrained strategem was ready by September 1964 and we were set to take on the river. Our challenge was to sail from Manampitya to Mutur – a distance of approximately 85 miles and hope our craft would take us safely to our destination at Kodiyar Bay, near Trincomalee.

At dawn on September 8, 1964, we arrived at Manampitya and made our way to the building site where the raft of bamboo poles and floats of banana trunks was soon assembled. Our builders who had little experience in such things assured us it should suffice to make the journey. When the raft was finally transported to the 60-foot steep banks of the river below the rail and road bridge, it was a memorable sight. The raft was a mere speck waiting to be swept away. The swiftly flowing Mahaweli ganga looked formidable, almost 300 yards broad at this point, carrying huge volumes of muddy water, and fallen foliage all the way from the hills 150 miles upstream.

The impact of large-scale damming and diversion projects had commenced, and determining the water levels of the river was problematic.

In fact, the river’s two main tributaries snake their way from the Peak Wilderness and Horton Plains at an elevation of 7000 feet. The southwest monsoon rains which had already commenced their drenching downpour brought a rush of flood waters and within a few minutes the water level would climb steeply at Manampitya.

We started off quite confidently and soon realized without a rudder we were at the mercy of the current and flow of the river. But on the other hand, because the bamboo craft was light and buoyant, we could paddle our way and drag our raft around sand banks and carry on downriver. But what was more perilous was that our feet and legs were exposed, dangling below water level.

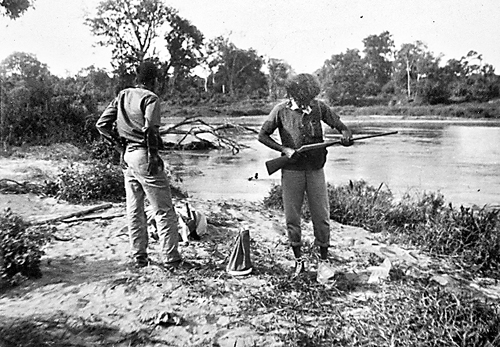

Breaking camp on the banks of the Mahaweli (5th day). The writer is seen (at right) examining the rifle

The river banks were invariably steeped in places 10-12 feet high, and huge Kumbuk, Palu, Milla and Satin wood trees that had keeled over as their roots were eroded by the swiftly flowing water were always much feared by us due to the driftwood, thorns and other snags that could inflict severe wounds.

In the evening, we would steer the craft to the bank, have a make-do meal with our stores of sodden rice, and pigeons that our marksman friend would bring down from the overhanging branches of the fig trees. Soon after such an exhausting day exposed to the sun and drenching water, we would collapse onto the soft sand, soon to be fast asleep. Often, we could hear the trumpeting and rumbling sounds of elephant herds. But we always chose a site which did not have signs of footprints of animals particularly elephants coming down to water.

But in the days of drifting, one sight was well worth the effort and dangers we risked. We came upon it by chance in the vicinity of the ferry crossing by the village of Katupillana.

Along the bank were some Muslim peasants bathing, washing and tending their cattle. They gestured to us, and drew our attention to a large boulder which we approached cautiously.

Soon to our amazement we realized it was a life-size sculpture of a magnificent elephant, chiselled out of the rock boulder and strategically placed among the other boulders. A perfect impression of a real elephant in knee-deep water wallowing and enjoying the cool waters of the Mahaweli. The sheer concept of this sculpture was itself breathtaking. The artisans and sculptors who carved it must have a marvellous aesthetic sense to have positioned the sculpture to give it full sense of place and naturalness. (see box)

In the last five years I have made at least three attempts to come within reach of the site at Katupillana, but have been discouraged from going further (presence of elephants and land mines) to locate it. I was assured by the local cattle herdsmen familiar with the river’s vicinity that the rock-cut elephant no longer exists and had been blasted by treasure hunters.

With 12 more days of rafting after encountering the Gal Aliya of Katupillana we were confronted with the choice of following one of two branches of the river.

The broader arm of the river makes its way to Mutur and the narrower waterway known as the Verugal winds up on the East coast. If we had chosen the Verugal Aru, the other main tributary, which was sedentary and slow, our journey would have been easier. Supposedly this was one of the earliest attempts to impound and divert the main river to feed the rice fields of the Eastern seaboard.

Shortly after passing the confluence of the two water courses we came upon a series of formidable rapids. After a short violent tremor, the raft came apart and the three of us swam ashore. After resting an hour and a gruelling 10-mile trek through villus with high elephant Mana grass we arrived at a small village north of Kandaikadu to a track that took us to the main Polonnaruwa – Batticaloa road from where we headed safely back home to Colombo.

| Katupillana elephant: The early accounts | |

| The only detailed published account of this monumental sculpture was by the Archaeological Commissioner H.C.P. Bell published in the Ceylon Antiquarian and Literary Register (Oct.1917) titled – The Gal Aliya at Katupillana and based on the notes taken during the archaeological circuit and explorations of the Tamankaduwa District carried out between August 4-October12 1897. His vivid descriptive text was accompanied by detailed measurements of the sculpture taken during the flow of the river “The left bank of the Mahaweli river the pseudo beast, fronting and in exceptional relief, owing to the isolation of this unlooked for tour de force of animal sculpture- just possibly the irresponsible freak of some skilled stone mason has left it –virtually unknown to Europeans”. Harry Storey, the well-known hunter in his much-read book Hunting and Shooting Ceylon wrote an account of the rediscovery of this stone elephant at Katupillana in 1907 on his visit to this site. This was his second visit and he took along his friend Cameron, probably the then Government Agent of Anuradhapura H.H.Cameron.

|