When elephants fight: Implications of US-China trade dispute on bystanders

After months of tension, a thaw in the US-China trade dispute is on the horizon, with the US agreeing to halt further tariff increases and China agreeing to buy US farm products. However, fundamental disagreements that led to the dispute—such as subsidies and intellectual property—are complex and remain unresolved. If the current detente does not hold and the planned across-the-board 25 per cent tariffs on China come to fruition, market disruptions will deepen, compounded by the latest US-EU dispute over subsidies—further impacting both winners and losers, altering how nations like Sri Lanka trade with the “giants” as the international trade regime inevitably shifts in the coming years. Experience provides some clues what may be in store and how bystanders like Sri Lanka can respond.

Dr. Nihal Pitigala.

Elephants are losing

Both parties to the dispute are facing negative impacts, with spillovers to third countries. The impacts to the US and China are transmitted through two channels. First is the “welfare effect” whereby increases in tariffs affect domestic production efficiency and lead to the reallocation of resources within the two economies, changing how much output can be generated, and through their effect on consumers through relative price changes. Second, a large country imposing higher tariffs faces a change in its “terms of trade”, though the outcomes are often ambiguous. In a scenario where there is retaliation, such as the US-China dispute, the outcome is more likely to lead to no change in the terms of trade, or even create a negative impact. The end result is likely to be a drastic reduction in the volume of trade—both imports and exports—without the assurance of an improvement in the terms of trade.

The evidence so far demonstrates that US losses are mainly in reduced welfare. US tariffs were almost completely passed through into increased domestic prices, with no impact so far on the prices received by foreign exporters. For example, prices of most consumer goods like washing machines rose by nearly 12 per cent since higher tariffs were imposed. Imported inputs to US producers have, instead, largely been absorbed by importing firms through lower profit margins. Apart from a few key success stories, like LG Electronics moving to Tennessee and Samsung Electronics to Texas, the bulk of reduced imports from China has been to offset imports from other countries rather than through the expansion of US production. Given the unmatched economies of scale in China (and, in some instances, subsidies) and the wide range of products it exports to the US, shifting production to either the US or third countries—at least in the immediate term—is not easily achieved without a substantial cost. In fact, only one-sixth of China’s market share of the US apparel market has been diverted to third countries since additional tariffs were imposed.

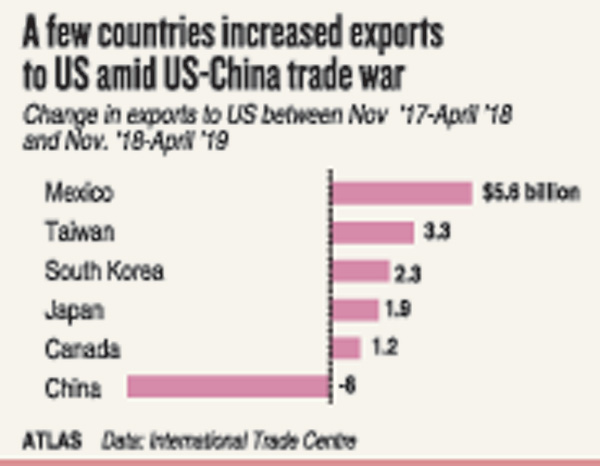

Battle for Spoils: Friends and neighbours first

Even a 1 per cent of diverted trade constitute significantly for small developing countries that are able to benefit as bystanders. The US tariffs on China have already created an export boon for Mexico and Vietnam, as well as for larger countries such as Canada. While most beneficiaries are US FTA partners, what is intriguing is Vietnam’s dramatic surge in exports to the US—$50.09 billion through the first eight months of 2019, an increase of a whopping 31 per cent over the previous year. While there is evidence that some of the increased trade may be transshipments (so-called ‘trade deflection’), there is also evidence that Vietnam has benefitted from increased investment in capacity in advance of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (now CPTPP without it)—boosted recently by the trade dispute. FDI inflows to Vietnam grew by 86.2 per cent year-on-year, to $10.8 billion with China accounting for half of that investment. For example, 60 components makers that supply Foxconn Technology Group and Samsung Electronics Co, among numerous others, have scrambled to shift production to an industrial park northeast of Hanoi in first half of 2019 to skirt US tariff hikes on China.

What favours Vietnam? First, Vietnam made large public investments to ensure minimum quality standards in education and human capital development to generate efficiencies into an already low-cost and abundant labour pool. This was necessary, as a growing population also meant a growing need for jobs. But Vietnam also invested heavily in infrastructure, ensuring cheap mass access to the Internet. Second, it undertook aggressive external and domestic reforms through deregulation, lowering the cost of doing business. Its industrial structure transformed into one of the most specular export performers in recent years.

A number of poorer countries—such as the Pacific islands of Micronesia and Nauru—also saw surges in exports of electrical switches to the US, and of skipjack tuna from Micronesia to China and integrated circuits to Malaysia. Since the dispute, Bangladesh’s garment sector has benefitted from a sourcing frenzy by US buyers to exploit the fall-out, with a 13 per cent increase in exports during the first half of 2019.

China’s retaliation in response has been strategically focused, mostly targeting agriculture exporters in the mid-West. The immediate beneficiaries are, by far, Australia and Brazil, large producers of soybean and meat, as well as Kuwait (propane) and Malaysia (waste scrap). Few other developing countries have made a dent in China’s imports due to the sheer scale of demand and the urgency of replacement stock and substitutability between similar products.

Few ominous signs of prolonged dispute

While the dispute creates short-term winners and losers, a prolonged dispute accompanied by subsidy-triggered US-EU tit-for-tat tariffs will exacerbate already weakened growth in the industrialized markets that most developing countries have relied upon as a conduit for growth and structural transformation. A likely aftermath is that global value chains that enabled firms in developing countries to specialise in different stages of production, enhancing efficiency and productivity, are now forced to re-think and re-align towards sub-optimal linkages, incurring high fixed and variable costs associated with shifting production simply in order to avoid tariffs.

Moving forward, should the US impose an across-the-board 25 per cent tariff on Chinese goods, the prolonged impact—coupled with longer-term decline in trust—may result in a dual system of supply chains and markets that will further fragment the global economy. Another residual result is the likelihood that China will divert some of its exports deflected from the US to developing countries, threatening their own manufacturing sectors.

Sri Lanka’s options

In the short-run, early winners in the trade disputes are most likely to face market adjustments over time, but those with preferential market access to the US will more likely be positioned to reinforce their advantage. For everyone else scrambling for market share up for grabs, taking advantage of trade diversion away from China, achieving short-term wins will come down, principally, to entrepreneurial abilities to exploit existing buyer-supplier relationships and building new networks within discrete product categories. The major US retailers are already rushing to Vietnam, Bangladesh and other places to ensure holiday season sales are met with minimum impact on profits and consumer prices. Sri Lankan industries must not remain idle bystanders but must actively pursue such opportunities to expand market share. In the medium term, there is also an opportunity to court investment from US firms seeking to diversify their supply chain—India is already using the dispute as a means to get its foot in the door to attract high-technology sectors.

In the long run, the dispute highlights a need for a more systemic approach that is responsive and resilient to evolving global market dynamics and changing technology (e.g. Fourth Industrial Revolution) as a means to reducing exposure to external vulnerabilities and sustaining growth.

In this context, a shift in focus towards Asia becomes imperative. Even though both India and China are now experiencing lower than anticipated growth, emerging Asia (along with Africa) will continue to drive global growth over the next few decades. India is set to grow at an annual average over 7 per cent and China, over 6 per cent (which is equal to the size of Sweden pumped into the world economy each year). Their maturing consumption (altogether Asia will account for 40 per cent of the world’s total consumption by 2040) – if met by open markets and shared tasks —could evolve into a new nexus for value chains to complement the existing US market-led model. In such a scenario, Sri Lanka’s unrivalled comparative advantage of geography would become even more potent than what it is now. New investments in ports and other related infrastructure are early signs of Sri Lanka’s future place in the shifting global economy.

But geography alone cannot assure Sri Lanka’s path to structural transformation and inclusive prosperity. Integrating deeply with Asian emerging markets is a critical conduit to securing markets and, more importantly, incentivizing investments. It is in this context that economic and other policies and programmes need to be retooled. This will require, to put it in broad terms, a proactive agenda to (1) prioritise human capital development (education and training), (2) create policies and institutions that foster innovation and technology absorption, (3) promote investments in world-class, technology-driven logistics and other supportive services, and (4) undertake domestic market and regulatory reforms to create an efficient, business-friendly environment.

((The writer is an Senior Economic Policy Analyst. He can be reached at nihalpitigala1@gmail.com).