Arts

Seeking empathy through the landscape unseen

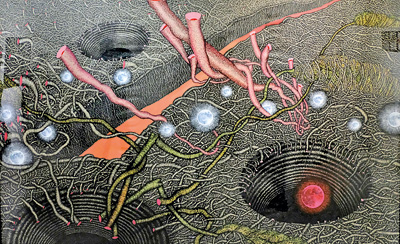

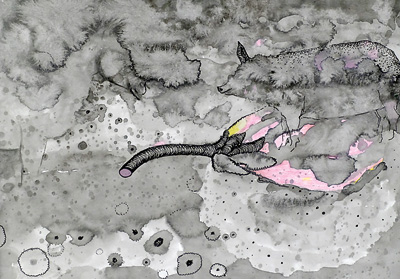

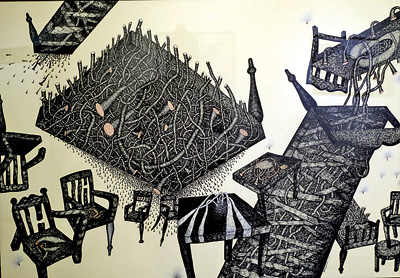

View(s):His detailed ink and watercolour drawings on paper are inspired by his own experiences of conflict during the years of war in the North. “The ‘Wounded Landscape’ portrays the reality of disappearances, unforgettable memories and events inextricably intertwined with the land. I continue to confront the chilling immediacy of disappeared people in the lands we live in whether it is Sri Lanka, Kashmir, Myanmar, Iraq, Palestine and so many places,” the artist says.

Pakkiyarajah Pushpakanthan and above, right and on our Magazine cover his works. Pix by Amila Gamage

Pakkiyarajah Pushpakanthan’s exhibition ‘Wounded Landscapes’ has been on at the Saskia Fernando Gallery over the past two weeks and ends on October 31.

The Batticaloa born artist has a Fine Arts degree from the University of Jaffna, and is a Lecturer in the Department of Visual and Technological Arts at the Swami Vipulananda Institute for Aesthetic Studies, Eastern University.

By exploring unforgettable memories of death, disappearance, torture and wounds, the artist uses his work as a space to lay bare the painful realities of the past so that people can grieve and heal. Rather than searching for answers of solutions, he moves through refined shifts of perception, hoping that the spectator is able to empathize with the trauma and its meaning.

“As a silent witness of stories past and present, the land holds evidence of every single experience: of joy and suffering, of life and death. The beautiful sights of stretching beaches, luscious jungles, and waterfalls of the island might also be terrifying, since they mask what could be, and often is, actually hidden. So, rather than the sensuous scenery that can be easily perceived, the landscape unseen — or forced to disappear— interests me more,” he says in his exhibition notes.

He has exhibited in Sri Lanka, India and the UK, and is represented by Saskia Fernando Gallery. His work is in private collections in Sri Lanka, Europe and North America and he is a recipient of a South Asia Studies Fellowship at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York.

“Violence and suffering may elicit different responses. For instance, while the pain is devastating in both cases, the Easter attack victims’ families were allowed to bury their dead, whereas the relatives of the war time disappeared are prevented from seeing their dead. For the latter, there is no closure, no opportunity to begin healing, and hope itself becomes torture. Through this series I attempt to express the fear and imaginings of the relatives of the missing. They grapple with the uncertainty that those who disappeared might still be suffering somewhere, and they need to share this trauma with others to come to terms with it,” he writes.