Sailing in dangerous waters

A fishing vessel moves out of the way of an ocean juggernaut. Image © Russell Leaper

To the south of Sri Lanka, there is one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world. The movement of ships takes place in two lanes, one travelling west and another east in what is known as the Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS). South of Dondra, this TSS runs as close as five nautical miles from the shore, so the ocean juggernauts using the shipping lanes are travelling through an area densely frequented by coastal fishing vessels.

As a result, a dangerous situation continues to grow in the south of Sri Lanka which on a daily basis places Sri Lankan fishermen at risk of being hit and killed by a large ocean-going ship. As the popularity of Sri Lanka grows for whale watching, the risk also increases of a collision with a commercial ship and a whale watching boat carrying local and foreign tourists.

A brief search on the internet for recent collisions brought up three incidents in 2018 where fishing vessels sank after collision with commercial shipping south of Dondra. In January 2018 and September 2018, fishermen died.Ninety per cent of the ships do not stop at a port in Sri Lanka and there is no requirement for the safety of ships that they should travel so close to shore.

In fact, the case is the opposite. The international shipping industry considers it safer for ships to be travelling further offshore, and a proposed shift further south of 15 nautical miles of the shipping lanes will result in a significant improvement in safety with only a tiny incremental addition to the total distance travelled by the ships.

Much of the conversation for moving the shipping lanes has been about moving them to stop whales from dying, because whales are also found in high numbers in this area, and there are many recorded incidents of whales being hit by large ships and being killed. I would like to change the focus to one of improving safety for people and shipping, and to prevent fishermen from dying. In this article, I also advocate that those charged with maritime safety in Sri Lanka should be the ones taking action to shift the shipping lanes further south and not leave the responsibility for taking the lead to a government ministry tasked with environmental issues.

This article is in response to a talk I attended in April 2019 given to the Friends of Sri Lanka Association at the Linnean Society in London, delivered by Susannah Calderan, a researcher working with the University of Ruhuna in Sri Lanka. The information I have used in this article is from the work by her and her colleagues. The talk flagged that no action had yet been taken on moving the shipping lanes further from the coast. I suspect one reason why action has been delayed is because the fundamental issue of maritime safety may have become muddled with that of environmental issues, to be driven by a government institution charged with an environmental responsibility. A preoccupation with whales and trying to find the right environmental agency to take this forward could leave the serious risk to people and shipping not being addressed.

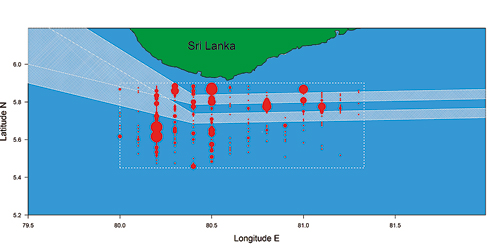

A combination of features including the topography of the oceanic floor, oceanic currents and monsoons creates an area close to the southern coast of Sri Lanka which is rich in nutrients and hence rich in marine life. This rich food web results in an area which is optimal for fishing. Unfortunately, before the richness of this area for marine life was fully understood, the shipping lanes were placed to run through this area. The diagram accompanying this article shows the presence of fishing vessels recorded on daytime surveys conducted on north to south transect lines superimposed on ship track data. The diagram makes clear the TSS is presently positioned too close to the shore, creating the risk of a collision for fishermen, whales and whale watching boats. When one considers that the fishing activity is much more intense at night, the danger to fishermen and shipping is even higher than that shown in the figure.

The situation is already so dangerous, that 26% of the shipping traffic in 2017 (up from 20% in 2013) is now operating outside the official TSS. Ships are electing to travel further away from the coast to avoid hitting fishing vessels and whale watching boats. Having a quarter of ships not following the official TSS presents its own challenges.

A letter dated April 7, 2017 highlighting the dangers from the perspective of the shipping industry due to the presence of fishing vessels was sent to the Prime Minister and copied to the Minister of Ports and Shipping, Director General of Merchant Shipping, Chairman of the Sri Lanka Ports Authority, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs and the High Commissioner in London. It was signed by senior officials from seven international shipping organisations. These are the Baltic and International Maritime Organisation (BIMCO), Cruise Lines International Association (CLIA), International Association of Dry Cargo Ship Owners (Intercargo), International Association of Independent Tanker Owners (Intertanko), International Parcel Tankers Association (IPTA) and World Shipping Council. They said ‘…..At the heart of these concerns is the presence of numerous, small fishing craft in the traffic separation zone and surrounding area …..’

The International Maritime Organization’s Marine Environment Protection Committee also recognised the risk in a paper MEPC 69/10/3 dated 12th February 2016. Point 18 of the paper noted the following. ‘………Results of surveys designed to investigate Blue Whale distribution in relation to shipping have suggested that shifting the current TSS to the south would substantially reduce the ship strike risk and improve maritime safety……….’

There appears to be no credible economic grounds for not moving the shipping lanes. After all, it is the international shipping industry that is pressing for the lanes to be moved further out to sea for safety. An alternative traffic separation scheme has been proposed which will be a further 15 nautical miles away from the current scheme. This will add a mere 5 nautical miles extra for ships travelling from or to the Red Sea and a mere 9 nautical miles to ships from the Arabian Gulf to the West Coast of India, for the approximately 90% of ships which do not stop in Colombo. For the approximately 10% of ships that do stop in a Sri Lankan port, an inshore traffic zone could be implemented. Moving the existing TSS further out is the preferred option for the shipping industry compared to a ‘go slow’ scheme.

The risk to fishing craft is not a new one, as press reports have over the years documented deaths from collisions. However, it has taken the development of whale watching for the poor positioning of the TSS to come to reach a wider audience. Given the seriousness of the danger to fishermen and tourists and evidenced by ships unilaterally electing to travel offshore of the current TSS for reasons of safety, it is best if timely action is taken to formally move the TSS further south.

Shipping lanes cutting through fishing vessels (red circles)

What needs to be done next? In Sri Lanka, the Merchant Shipping Secretariat (under the Ministry of Ports) is the local regulator and is empowered to take action to propose moving the shipping lanes through the mechanism of the International Maritime Organization (IMO). The Sri Lankan government first needs to submit a routing proposal to the IMO’s subcommittee on Navigation, Communications and Search and Rescue (NCSR); this is a subcommittee of the Maritime Safety Committee. The IMO Secretariat has already offered to help Sri Lanka (including possible funding) with the technical details of a proposal, including consultation with the International Association of Marine Aids to Navigation and Lighthouse Authorities (IALA), the international body that provides technical advice on the design of Traffic Separation Schemes.

I hope someone who reads this article and is sufficiently influential can get the wheels of machinery in government moving to improve maritime safety to protect Sri Lankan fishermen and the shipping industry.