News

Water for jumbos, fences for humans: new minister seeks solutions

More reservoirs will be constructed in forests so that thirsty elephants do not invade human settlements in search of water, the Minister of Environment and Wildlife, Lands and Land Development, S.M. Chandrasena, said as a leading expert also called for forest water sources to be developed.

An elephant found dead in the premises of a home in Medawachchiya. Pic by Athula Bandara

To meet concerns posed by the human-elephant conflict – an issue addressed directly in President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s election manifesto – the new minister vowed he would personally investigate the issue.

“I will visit all the districts personally and take the initiatives to mitigate the problems,” Mr. Chandrasena said.

He will put 2,000 Civil Defence officers onto the job of mitigating human-elephant conflict.

Electronic fences appear to be still regarded as the main defence for vulnerable villagers, with Minister Chandrasena saying he would order that such fences be reinforced.

This will come as a relief to villagers who say some fences are in disrepair, but environmentalists have long pointed out that the fences and human settlement have broken up elephant ranges, cutting the animals off from traditional sources of food and water.

Leading conservationist Sajeewa Chamikara said elephants faced a tragic future because their territory was being gradually stripped away.

Forest areas had been reduced due to large-scale development projects and cultivation such as sugarcane cultivation, depriving the animals of their natural habitat.

The Moragahakanda and Kaluganga development projects resulted in the clearing of more than 25,000 acres of the Knuckles and Wasgamuwa reservations, severely affecting living conditions for the elephants that ranged there, said Mr. Chamikara, who heads the Environmental Conservation Trust.

Under the Magampura Port project, the government handed over the port and 15,000 acres of land around it for 99 years to China, depriving elephants of their Hambantota and Monaragala habitat.

The area identified for inundation in the proposed lower Malwathu Oya reservoir plan – to create 2,000 more acres of irrigable paddy land – is also the natural habitat of elephants and other wild animals. The project will separate one part of elephant habitat from another, limiting their ability to forage for food in tough times, Mr. Chamikaa said.

The accelerated Mahaweli L project will take away another 66,000 acres from wildlife reservations.

“The lack of land for elephants to live is the foremost reason for human-elephant conflict,” Mr. Chamikara said. “The main reason for their invasion of villages is as they have lost their habitats.”

Preventing human settlement in forests was crucial, he said.

“It is particularly important to develop the water sources in the forests,” Mr. Chamikara emphasised.

He said a good approach to elephant conservation would be to join protected areas into a network as elephant habitat was being reduced to fragments.

“Demarcation of the areas would be considered a great example of solving human-elephant conflict,” he said.

Territory that had not been classified as “protected”, which is owned by the Land Reform Commission and the Mahaweli Authority should be added to protected areas, he added.

Mr. Chamikara pointed out that simply being termed “protected” does not ensure the sustainable conservation of these beings and that habitat conditions in these protected areas must be enhanced.

“If we are confining the elephants to protected areas they should fulfill their needs,” he said.

In most areas near the Lunugamwehera and Maduruoya reservoirs, invasive plants now dominate the vegetation, making it difficult for elephants to find vegetation they can consume, Mr. Chamikara said.

“Invasive plants such as spiny bamboo, lantana and guinea grass have covered their food areas and sometimes elephants don’t even go where these plants are growing because of their smell,” he said.

Environmentalist Parami Weediyarathna said human-elephant conflict could be reduced by 75 per cent if electrified fences were properly maintained.

“The elephants’ range extends outside protected areas into human settlements and agricultural areas so elephant corridors must be established with proper care,” he said.

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa outlined in his election manifesto a clear programme to mitigate human-elephant conflict.

“We shall bring in amendments to existing laws and, if necessary, new legislation will be introduced in order to strengthen and protect our forest cover, rivers, streams and wildlife,” he states.

“A common problem is the man-made disaster of the human elephant conflict which has had a toll on both man and elephant. Therefore, a permanent solution is a must.”

He promised to act swiftly to build electric fences that elephants could not damage or dislodge and to provide financial assistance to all those who have had their homes and property damaged or destroyed by elephants, or who have been injured or had a family member killed in elephant attacks.

The President said the government would identify and protect waterholes used by elephants.

He promised to take strong legal action against people found to be guilty of the brutal killing of elephants.

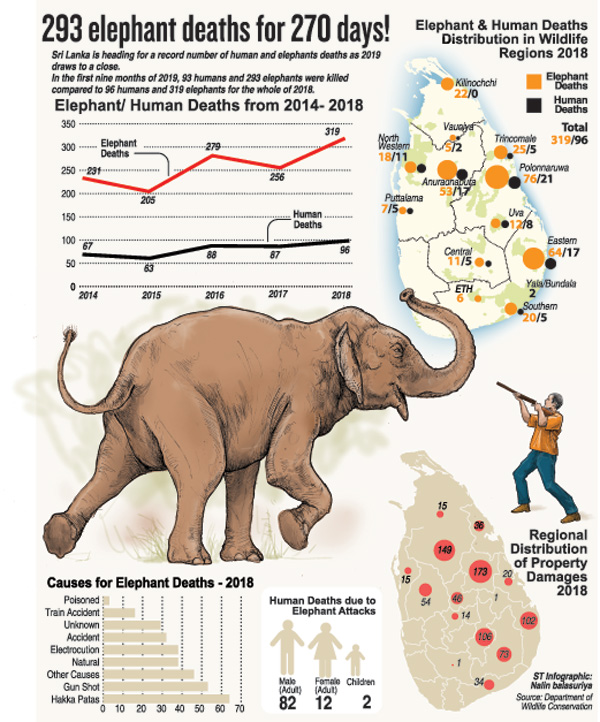

Wildlife officials said 350 wild elephants had died so far this year, many of them killed by human hand through being shot, attacked with explosive devices, powerful fireworks (hakka patas) used to frighten them off, or poison. Some had died through electrocution, falling into wells and road and rail accidents. Other deaths were, of course, due to natural causes.

Elephant attacks had killed 106 humans in the same period.

Ampara, Anuradhapura, Puttalam and Polonnaruwa are the most commonly reported areas of human-elephant conflict.

| Attacks keep villagers fearful at night | |

| Pix and text by Hiran Priyankara Jayasinghe and Mohamed Buhardeen More than 55,000 families living in villages in the Puttalam and Matale districts are facing increasingly high levels of threat from elephants and are abandoning cultivable land to stay safe. Wild elephants continually roam these villages at night, damaging crops and homes, sometimes attacking residents. A third of the 16 Puttalam divisional secretariats are subject to severe attacks while minor damage is reported in other divisions. The vulnerable areas include 460 villages in Anamaduwa, Navagaththegama, Maha Kambukkadawala, Karuwalgaswewa, Wanathamulla and Pallama. About 200,000 people here live in fear of harm to life and property. Elephant attacks have become a serious problem, Puttalam Distict Secretary N.H.M. Chitrananda said. “As a result, there are many cultivable lands abandoned in our district,” he added.  Destruction to property and cultivation “When attacked by elephants, we are given compensation only for deaths or attacks. I have made many appeals to the higher officers asking for compensation for other damage too, but all in vain,” he said. The officer in charge of the Wild Elephant Controlling Unit in Puttalam, W.M.K.B.N. Bandara, said he lacks resources to help the villagers adequately. “We are making a great effort to drive the elephants away but the dearth of officers poses a problem,” Mr. Bandara said. In the Galewela area of the Matale district, 5,000 families face high levels of conflict with elephants. People living in Dadubendiruppa, Hinukgala, Damana, Dewahuwa, Wetakoluwala, Pibidunugama and Galpaya are the worst affected. They say elephants from the Ranawa forest reserve enter villages at night and early in the mornings, laying waste to the paddy harvest and damaging homes. The elephants arrive as early as 6pm, making it hazardous for villagers who have gone to work to return to their homes. Residents say they cannot even go to the nearest hospital at night in the event of sudden illness, due to fear of elephant attack. “This is not something that has happened recently: we have been facing this for 15 years,” said Thilak Mudalige, a victim of an elephant attack. “Elephants invaded the lands when we are about to collect the annual harvest and they destroy the houses,” he said. Residents said the Department of Wildlife Conservation has not provided solutions. “Many of the villagers get into debt to cultivate their fields, and when elephants attack the crops they are unable to pay their debts,” he said. Homes built with hard-earned money saved over years are demolished by elephants in one night. Two weeks ago, elephants attacked a mango cultivation and pushed one of the trees onto the owner’s house. The inmates narrowly escaped death. Villages said that electric fences have not been a solution as the elephants break through the fences. |