News

Fish, the ignored wildlife on our plates

On World Wildlife Day next Tuesday, charismatic wildlife such as endangered elephants, leopards and the vulnerable sloth bear will take the stage – but one species is routinely ignored, to our peril.

Diverse fish species on a common malu lella

There will be protests to protect forests such as Wilpattu, Sinharaja and even mangroves. “But are we concerned enough about the conservation of marine species and the marine ecosystems that support them?” questioned Nishan Perera, marine biologist at the Blue Resources Trust.

“As a society, we do not traditionally consider fish as wildlife, only as food. This perception has become a block in conserving our marine resources,” he said in an address to the Wildlife and Nature Protection Society.

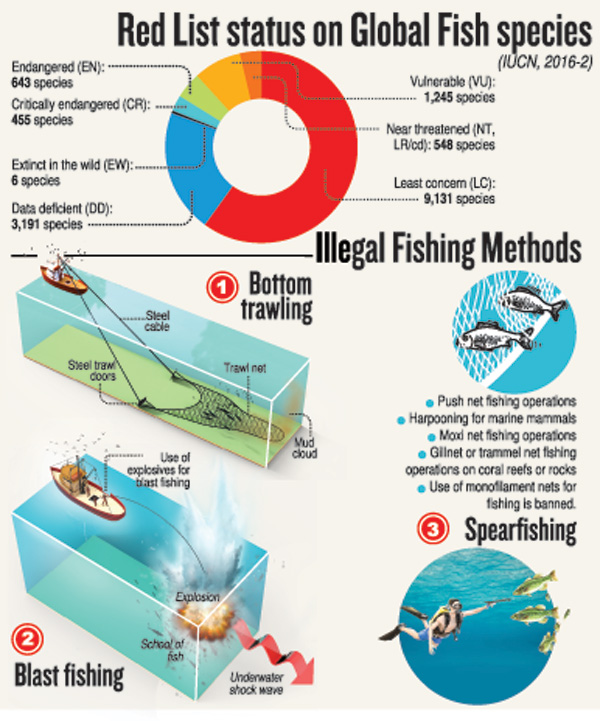

The popular yellow-fin tuna (Thunnus albacares), locally known as kelawalla, is now “near-threatened” according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species.

Its cousin in the Atlantic Ocean, the bluefin tuna (Thunnus thynnus) is already categorised as “endangered” due to overfishing. Many species of sharks and rays are termed “vulnerable”.

“endangered” fish species such as hump-head wrass (Cheilinus undulates) end up on our plates.

According to the Red List, overfishing has pushed two families of rays, wedgefishes and giant guitarfishes in Sri Lankan waters to the brink of extinction, their populations declining more than 80 per cent in the past 45 years.

Sadly, these fish are not even being targeted by fishermen but simply caught most often as bycatch – captured accidentally in nets. Most rays and sharks are slow breeders.

Rays are a threatened species, but a large number of them are killed everyday. Pic courtesy Daniel Fernando

“I dive in many places around Sri Lanka and witness a lot of illegal fishing activity,” Mr. Perera said, citing over-large nets, dynamiting and bottom-trawling among such illegal fishing methods.

“We shouldn’t be sympathetic towards these fishermen. Stringent measures have to be taken,” he urged.

Resources are not always aimed at priority interventions. A prime example, Mr. Perera said, was the case of several teams being deployed to protect the southern elephant seal from the Antarctic that came accidentally into local waters while not using similar efforts to curb everyday violations of fishing around Colombo.

“Building innovative public-private partnerships, empowering local communities to help with surveillance and monitoring, and increasing communication and networking are cost-effective ways of improving management,” Mr. Perera said in his lecture, delivered on February 20.

“This has been done in many other developing nations such as Maldives, Kenya, Tanzania, Indonesia, Philippines, and Fiji.

“Increasing funding alone will not solve the problem. Many past conservation projects have resulted in large sums of money being spent with little to no change on the ground.”

There is little enforcement even for the protected marine sanctuaries, Mr. Perera said, pointing out that the Department of Wildlife Conservation lacked manpower and direction to conserve marine wildlife.

Mr. Perera said Sri Lanka needs to declare more marine protected areas to lessen the damage from unsustainable fishing but admitted this was not easy.

“The recent declaration of a small area of around 950ha as the Kayankerni Marine Sanctuary was opposed by the fisheries lobby even though only a few fishermen actually fish within the sanctuary, and it was agreed to allow limited, regulated fishing within the sanctuary,” he said.

Almost 99 per cent of the east coast remained open to fishing and the areas under protection were very small.

Protected areas can act as breeding grounds, with excess fish moving outside the protected area and having positive impacts on fish catches in the long term. This is well documented in other countries, Mr. Perera said.