Sanders stays upbeat but concerns grow after difficult night

Despite promising signs in California and among Latinos, there are several reasons for the Vermont senator to worry

When Bernie Sanders came out to face his supporters in his home town of Burlington, Vermont, on Tuesday night he projected no signs of self-doubt. “We are going to defeat Trump because we are putting together an unprecedented grassroots multi-generational, multi-racial movement,” he boomed, thumping the podium.

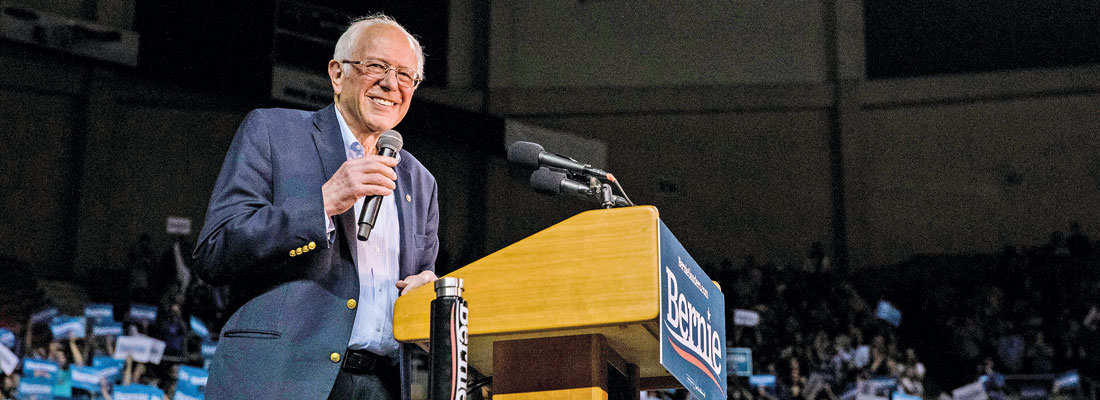

Democratic Presidential Candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) campaigns at Arizona Veterans Memorial Coliseum on March 5, 2020 in Phoenix, Arizona. Sanders encouraged attendees to get out the vote ahead of the March 17 Arizona primary

Even by that point in the night, though, the Super Tuesday results were pointing to a movement coalescing not around Sanders but around his resurgent opponent Joe Biden. By the morning after, the hangover had worsened – data from several states suggested that Sanders’ core support had softened a little and had doggedly failed to expand.

Vermont, the bastion of the Sanders revolution since he won his first mayoral election in Burlington exactly 39 years ago to the day – 3 March 1981 – itself told a story. In 2016 Sanders polled 116,000 votes in his home state to Hillary Clinton’s 18,000; on Tuesday he gained 80,000 to Biden’s 35,000.

Certainly, there were positive takeaways for the night for Sanders. California, the biggest prize, gave him a much-needed shot in the arm with his 34% to Biden’s 25% victory.

Sanders made large and possibly game-changing strides with Latino voters here, building on his success among this demographic in Nevada. Some 55% of Latinos came out for him in California and a stunning 84% of younger Latinos aged 18 to 29.

Sanders will cling to those achievements as the next stage of the primary contest now opens, arguing with some justification that the youth insurgency he unleashed in 2016 has matured in 2020 into a young, liberal, Latino insurgency which can take on Trump. As he told his people in Burlington on Tuesday night: “You cannot beat Trump with the same-old, same-old kind of politics.”

But against those promising signals there are many reasons for anxiety tucked into the Super Tuesday vote. Perhaps the greatest cause for concern is the most simple – the moderate alternative voice to Sanders, which stands for evolution rather than revolution, regaining America’s dignity rather than transforming the nation, has finally taken form in Biden.

Nowhere was that clearer than in Minnesota, the upper midwestern state that Sanders won handsomely in 2016 by 62% to Clinton’s 38% (it ran a caucus system in 2016 and has since changed to a primary). On Tuesday Biden took the state by 39% to Sanders’ 30%. Exit polls suggested that about half of the voters in Minnesota had decided their vote just in the last few days, underlining the importance of Amy Klobuchar, the home US senator, quitting the race on Monday and endorsing Biden. That pattern of a rapidly congealing coalition – you might use Sanders’ own word, “movement” – forming around Biden is bound to intensify with Tuesday’s departure of the billionaire former mayor of New York, Michael Bloomberg.

With Sanders no longer able to benefit from the splintering of the moderates, he must now also worry about the struggle he has experienced to deliver on his main promise: turnout. He told his crowd on Tuesday night that he would secure “the highest voter turnout in American political history” – but that task is proving elusive.

Nate Silver, editor of the political analysis website FiveThirtyEight, noted that the most notable turnout of the night was in Virginia, which Biden won by 30 points, surging from about 800,000 to 1.3m. “It doesn’t seem great for Sanders’ electability narrative that turnout seems to be increasing more in states where he isn’t doing as well,” Silver said in a tweet.

Even his core base – young voters – who are absolutely essential to his vision of a transformative moment in American history, seem to have missed the message. Exit polls used by a number of news outlets showed that while California lived up to Sanders’ dream of a youth revolution with seven out of 10 young voters turning out for him, in North Carolina the proportion of youth support actually fell from 69% in 2016 to 57% in 2020.

There will also need to be some difficult de-briefing in the Sanders camp over data that suggests that support for his individual policies – notably government-run universal healthcare – did not translate into votes. In Alabama, Massachusetts, Minnesota, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas and Virginia, exit polls from Super Tuesday suggested that at least half of all Democratic voters support Medicare for All, yet these states all went for Biden, who opposes the idea.

So there is a lot to think about as the contest marches on to a flurry of states, including delegate-rich Michigan, on 10 March, and Arizona, Florida, Illinois and Ohio on 17 March. Does Sanders hold firm and try and rekindle his “unprecedented movement” in the face of Biden’s explosive rise, or does he try something new as suggested by his latest campaign ad in Florida that shows him embracing, and embraced by, Barack Obama?

Courtesy Guardian