Living in a ghost town

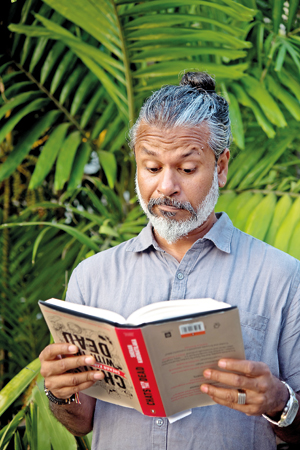

Is someone whispering in your ear: Shehan Karunatilaka. Pix ©Deshan Tennekoon 2020

The following constitute the (brutally-abbreviated) highlights of those proceedings.

AS: Why a book about ghosts?

SK: During the last ten years of touring with Chinaman, an old lady in Seattle wanted to know if I think Murali chucks, and Sourav Ganguly asked me publicly if I thought Sanga and Mahela were jealous of each other. I’m not really qualified to answer these things – so I thought the next book I wrote ought to be something as far away from cricket as possible. Hence a book about ghosts.

Can you give us a quick plot summary?

I call it ‘a black comedy about ghosts’; but conceptually, Chats is a murder mystery. It’s set in 1989, and it’s about a dead atheist, nihilist, hedonist war-photographer called Malinda (‘Maali’) Almeida, who’s travelled the island and seen carnage on an epic scale, and therefore believes that there cannot be a God, and cannot be any order to this universe, and much to his dismay he wakes up to find that there is an afterlife, and he needs to work out the rules. And the rest of the story is about him solving his own murder. Basically he ends up chatting to other ghosts, and, unfortunately, there were a lot of dead people in Colombo ‘round that time, a lot of bodies, a lot of unmarked graves, so there were plenty of ghosts for him to chat to.

Why 1989?

Cowardice, mainly. In the aftermath of the war, around 2012-2013, there was basically this sort of ‘battle of the documentaries’. Channel 4 brought out ‘Sri Lanka’s Killing Fields’, and then the government brought out a counter-documentary, that said, “Yeah, these people died here, but it wasn’t us, it was them” – and it just occurred to me that if anyone could interview the dead, maybe they could tell us who was pulling the triggers. But of course I was a bit nervous about writing about 2009, or even making sense of it – and then I realised that violence is not something limited to this century: we’ve had it all throughout our turbulent history, not least in the last 70 years. I might have written about ‘83, and someone should: I just didn’t feel qualified, as a Sinhala Buddhist. But ‘89 was the perfect storm: you had the LTTE, you had the IPKF fighting them, you had the JVP who had become militant, and you had the government death squads. And by the time I came to write it, everyone was dead – the victims and the perpetrators – so I felt I could get away with it.

So how do you research a project like this?

The research for Chinaman was watching cricket and hanging out with drunks – which I conducted meticulously. This time, I had to actually talk to dead people, and there weren’t many willing to be interviewed. I did some road trips, and visited haunted houses, and went to some freaky places, and of course I watched horror movies. In the best horror movies, you never see the ghost. But I had a bit of a problem, because on the first page, my ghost says, “Hi, I’m a ghost, and this is me…” I haven’t seen a ghost myself, and don’t particularly want to. But there are some people who say that they have: so I interviewed them.

Tell us about the afterlife that you’ve created.

I had to invent a situation that was plausible, and I went to philosophy, to religion, to holy people – but no-one knows what the afterlife looks like, so I thought it was entirely possible that it is like the passport office, where all these souls are not sure which counter to go to, which door to step through, which light to go towards, whether they’re supposed to forget their past life or to dig it up and repent of their sins. I’m not capable of writing proper horror, and I thought the absurdity of an afterlife like that could be mined for both comedy and tragedy. The rest of the theology is a mash-up, really, from local folk culture, the Tibetan Book of the Dead, people’s near-death experiences, karma, Theravada and Mahayana Buddhist traditions, urban legends… And in the background, the idea of this beautiful island having been subjected to Kuveni’s curse.

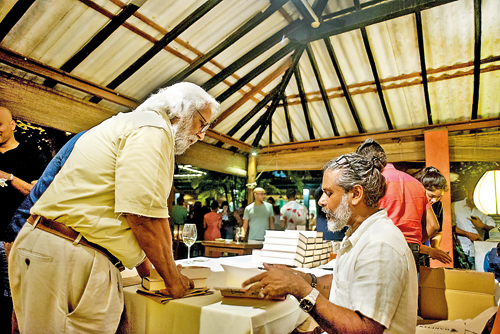

Ten years after Chinaman: Shehan signing books at Barefoot

Somewhat unusually, the book’s narrated in the second person. Why?

Initially, I wrote it in the first person; but I found it hard to separate Maali’s voice from mine – and then I just looked at it physically: we know the body dies, and the body decays, we see that. So what survives death? What is the soul? Is it breath, or what? And I came to the conclusion that what survives is the voice in your head. And I don’t know what the voice in your head sounds like, but mine is in the second person, and it’s always “You, you, you, you – you idiot!” When I took that on board, the book starting moving forward. But I had often wondered, are your thoughts even your own? Why is that song in your head all morning? Is it cos you heard it on the radio, or is someone singing to you? And all the bad ideas you have: do they come from you, or is there someone whispering malevolently in your ear? That opened up a lot of possibilities.

Maali’s homosexuality is central to the progress of the book. How did you come to have a gay protagonist?

So, you start from a lazy place: from real life. I thought, what if the fallen of ‘89 – Richard de Zoysa’s ghost and Rajini Thiranagama’s ghost and Rohana Wijeweera’s ghost – were having an argument in the afterlife? Gradually, as the drafts progressed, the characters moved away from those real lives; originally, Maali was very much like Richard de Zoysa, a thespian activist and so on – but when I made him a war-photographer he kind of took on a character of his own. But his sexuality remained, and I think it was useful because it meant I was more interested in his relationships. But I didn’t research that as extensively as I did drunkenness!

Though Chats is about a war-photographer, pretty much all the action occurs in Colombo. And Maali has a kind of love-hate relationship with ‘middle-class Colombians’…

Maali’s in the Colombo bubble, but he’s quite cynical about it, because he feels guilty about his own privileged background, and he looks around at people with scorn and disdain, and maybe that’s why he goes out to war zones to photograph things ’cos he feels this kind of Sinhala middle-class privileged guilt. With Chats, I felt that maybe I should talk about the things I didn’t want to talk about in Chinaman, so the war is pretty front-and-centre throughout. But yeah, the Colombo bubble is definitely a theme – and if you’re writing in English you have to accept you’re part of it.

Ghosts, deities, and talking animals. Did/Do you think of Chats in terms of magic realism?

I studied lit back in the day, and I’ve often thought that ‘magic realism’ was just a posh way of describing fantasy, horror and sci-fi. If you put a dragon in your book, it’s fantasy; if the dragon speaks Sinhala and opposes the 19th Amendment, then it’s magic realism. I would say that Chats is in the fantasy-horror-ghost genre; but if calling it magic realism will help me win the Booker, why not?

Chats with the Dead is out now, published by Penguin India. The UK rights have been sold to Sort Of Books.

Chinaman has been reprinted – for the umpteenth time (also by Penguin India) – in a new, 10th Anniversary Edition cover.

(Please see for an extract from Chats with the Dead)

| Ten years ago, A.S.H. Smyth wrote the world’s first review of Chinaman, for this newspaper. Last week, he interviewed Shehan Karunatilaka at the launch of his new novel, Chats with the Dead, at Barefoot Gallery | |