News

Acting faster than COVID-19 spread: Lanka’s ‘Operation contact tracing’

On Wednesday, Sri Lanka recorded its third death from COVID-19. A man from Maradana succumbed en route to the Infectious Diseases Hospital (IDH) from Sri Jayawardenapura Hospital where he had sought treatment, well after his affliction had worsened.

As with any other confirmed coronavirus case, this was worrisome. But more so because the 74-year-old was from a crowded neighbourhood. The National Housing Flats at Imamul Aroos Mawatha, Colombo-10, teemed with families.

The man was ill for several days, so friends and relatives had visited. “We found he had around 60 contacts,” said Dr Ruwan Wijemuni, Chief Medical Officer of the Colombo Municipal Council. “We cracked our heads over this.”

Contact tracing

Contact tracing involves questioning each COVID-19 infected person—or, in this case, those closest to him—to determine who else might have already acquired the virus from him, or been exposed.

It was quickly found that the deceased from Maradana may have contracted the illness from his daughter-in-law’s father who had met some textile agents from Chennai on March 10 before visiting the victim on March 28. Another son runs a travel agency but claimed he stopped work in early March. Both potential carriers still show no symptoms.

The area the deceased had lived in was encircled by military. There was intense investigation to map contacts.Just a few hours after his demise, eight members of the victim’s family were dispatched to a quarantine camp in Puttalam. And, within 24 hours, residents of four apartment blocks around his house were taken in buses to the Punanai camp in the East. The decision was prompted by the neighbourhood’s high population density.

The son-in-law and grandson also tested COVID-19 positive and are at IDH. The networks were fast branching out. Several families in De Vos Lane, Grandpass, made their way into quarantine. Two of his other sons are in self-isolation with their families. So are five work associates of one of them.

Altogether, 327 persons were sent to quarantine camps over that one case. Many more are in self-isolation. The numbers may seem high. But the authorities prefer to err on the side of caution.

Travel bans

Sri Lanka also took some early measures the authorities now feel were useful. From March 13, the Government started imposing travel restrictions on selected countries after first deciding that passengers from some nations could enter but would have to go into quarantine.

Soon, all arrivals were stopped and departures limited to outbound passengers (including tourists) and cargo. SriLankan flights going out came back empty. Sea ports were similarly closed. And container clearance was restricted to essential items to avoid crowding. There is now a pile-up of cargo at the port. And, as of this week, the national carrier is grounded.

But special flights did bring back hundreds of Buddhist pilgrims stranded in India before that country closed its airports. They, too, are in self-quarantine with the last aircraft having landed in Katunayake on March 22.

Groups who came before the bans did largely go into quarantine. But there was a significant gap because of protests over the designation of the Leprosy Hospital in Hendala, police said. This forced close surveillance of areas in the Gampaha District that were home to the so-called “Italy crowd” (although certain arrivals from South Korea were also in question).

The first local case — the tour guide from Mattegoda who worked with Italian tourists — was detected on March 8 and confirmed three days later. Schools and universities were declared closed. It also prompted the total ban of arrivals from Italy, South Korea and Iran and drew public criticism that passengers from China were not similarly blocked.

But the Chinese, by then, had a handle on the disease. Respective companies took individual responsibility to ensure their employees spent the recommended period in strict isolation. CHEC Port City Colombo even sent their workers onto a barge outside the Colombo harbour.

After observing the trajectory and determining the message wider dissemination, discussions were held with mobile service providers who agreed to introduce a special ringtone that hands out advice on the virus in all three languages. This was done by March 17.

Perfecting monitoring

Mapping the tour-guide’s contacts was a challenge. SIS worked both backwards and forwards. The Italians he worked with had already flown out. But everyone down to Immigration Authority officials and other airport workers as well as their respective families who dealt with the group were identified and sent into self-quarantine.

Drivers and other guides at the various hotels who came into contact with the patient were painstakingly traced, some from scribbles and “half names” they left on paperwork. The Ayurveda centre where the patient took treatment was closed down and thirty people there sent into self-quarantine along with their relatives.

“It’s easy for me to tell you how it happened,” a senior official said. “But it takes so much work.”

Intelligence also analysed arrivals data and estimated that there were around 33,000 persons at large that needed self-quarantining. The Defence Ministry urged all Sri Lankans who had arrived from European countries and Britain, Iran, Italy and South Korea between March 1 and 15 to immediately register with the nearest police stations.

A massive 8,437 registered—4,498 from the Western province, 1,187 from the Central province and 742 from the North Western province. At police stations, they were asked three questions including their travel history and this was independently verified by SIS, including from Immigration authorities.

Altogether, 27,000 were subsequently sent into self-isolation. A system of monitoring then evolved involving PHIs, intelligence and police. The Health Inspectors paste notices on the respective homes and visit them regularly. Local police were assigned a designated number of households to ensure they did not violate the rules. This continues to date.

These persons are still in self-quarantine and will receive a certificate of clearance from the PHIs when done.

On March 17, the Government gave the public and private sector leave for three days. This soon developed into a series of curfews but only after nominations for the general election—originally scheduled for April 25—were closed. Now, there is complete lockdown.

Don’t lie, don’t hide

“Everybody has one big question,” said one official earlier quoted. “Will this spread?”

Nobody, he says, has the answer to that. But if these mechanisms—and others that may emerge—are followed, the situation can be managed. It hasn’t yet developed into a full-blown community crisis, largely owing to the measures taken.

Much depends on human behaviour. Hiding out or lying to the authorities must be avoided at all costs. But it continues. One man who had recently been in India took his 85-year-old father to the Sri Jayawardenapura hospital and a private hospital. He did not disclose his travel history. And he had not registered with the police as required. His father tested positive and staff at both hospitals were exposed and needed self-quarantining.

Gatherings amidst curfew are another challenge. Around 75 people assembled for a function at a mosque in Beruwala. True, the crowds were fewer than originally planned. But it was a violation, nevertheless.

Do not do this, the authorities assert. It will have far-reaching effects on entire populations. “Don’t hide if you associated with someone with the disease,” the officer said. “Do not move out of your homes. If outside, maintain a one metre gap with others. We are working 24 hours based on methodically gathered information that is scientifically verified. Please be responsible and understand the situation.”

| SIS leads the way along with PHIs, military and policeThe State Intelligence Service (SIS) is the lead agency assigned with contact tracing in Sri Lanka’s COVID-19 epidemic. By now, it has a solid mechanism in place. At the highest level, SIS collates and analyses data to map the networks each COVID-19 positive person came into contact with. Its information is then used by health authorities, particularly Public Health Inspectors, military and police, to isolate or quarantine persons. Ground investigations are done by SIS together with the PHIs, military and police. The troops play a pivotal role at quarantine centres. They also cordon off areas, shift people and provide all manner of support. “We have one of the finest medical systems in the world involving midwives, PHIs, etc,” a senior security official said. “It was easy to couple it with the military, police and intelligence.” The police, meanwhile, have become faster at receiving and implementing orders. “They used to wait till instructions came in writing,” said an internal source. “Now, the IGP has created a system on Whatsapp. Once a circular is issued or particular decision is made, it is communicated to the ground immediately through Whatsapp.” | |

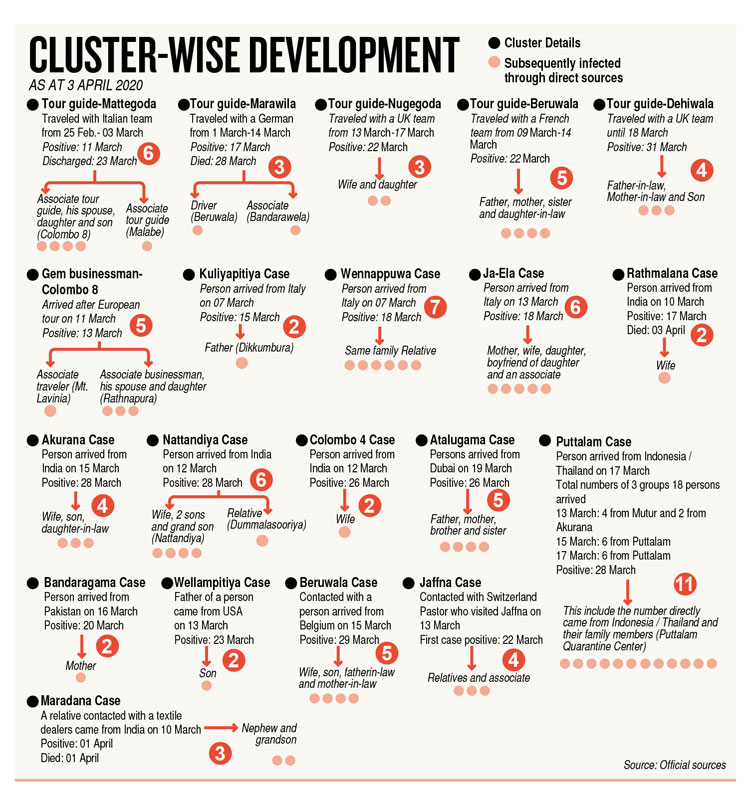

| Getting across vital info to Tamil-speaking communities The Government has identified that vital messages about COVID-19 are not reaching the Tamil speaking communities because of a communication gap. Discussions were held in an effort to correct the shortfall. This week, an ad hoc committee comprising, among others, religious leaders and civil society participants was set up to take the message out more suitably and effectively. There will be information via televised sermons, voice messages, social media campaigns and poster campaigns targeting the Tamil speaking communities. So far the spread is “cluster-based” So far, the spread of COVID-19 in Sri Lanka has been largely “cluster-based”. Groups of cases are linked because they have been in the same place together. “Community transmission” — where the illness spreads in such a way that the source of infection is unknown — is a worse scenario. One established case of community transmission is that of Chandima Hulangamuwa, the Managing Director of MSC Lanka (Pvt) Ltd, who recovered from the disease after 14 days at IDH but can’t say where he picked it up from. There are at least two more. Sri Lanka’s strategy is aggressive but, argue the authorities, it has paid dividends. A Switzerland-based pastor who led a prayer service in Ariyalai, Jaffna, before flying back home to find he was COVID-19 positive. A curfew was imposed over the entire district. A person who visited the pastor during his stay in the Northern Peninsula was soon diagnosed with the disease. Separately, 20 others who had close contact with the pastor were quarantined at Thalsevana, the military-run holiday resort in Kankesanthurai. By Friday, six had tested positive. “What if we hadn’t taken that action?” asked a senior official. Mass quarantines seem likely to continue but, as the numbers rise, finding space will become increasingly difficult. This is just one reason why the public must obey rules and stay inside. A single infected person causes a domino effect that can severely overwhelm services. When a 64-year-old man from Kochchikade died of COVID-19 at the District General Hospital in Negombo after having also sought treatment at a private hospital in the city, a large number of employees at both locations were forced to self-quarantine. More than 40 other contacts were sent into quarantine at Punanai. These measures take money, time and energy from a dedicated team of, by now, exhausted people. If going into quarantine is inconvenient, it is that much more difficult for those who make things happen. For the PHIs to the army to medical staff and police, this nightmare is magnified. “Because of one person, the amount of effort is enormous,” said one staff officer who did not wish to be named. From Beruwala, too, more than 220 were dispatched to quarantine centres. And everything takes place within 24, sometimes 12, hours: “We have to act faster than the spread.”

|