Depicting the Buddha

His image is so commonplace that you could believe it must always have existed — yet for six centuries after his death, he was never once depicted in human form.

A headless seated Buddha, from approximately A.D. 200 to 300, made in Mathura, in what is now central India. Mathura was one of the earliest and most important sites for the development of the Buddha’s image. Artisans there often worked in red sandstone with white spots.Buddha, circa 200-300, sandstone, Mathura, Uttar Pradesh, India, Asian Art Museum, the Avery Brundage Collection, photo © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

WE FLEW THROUGH the thin, light-suffused mist of a December afternoon in north India before landing among open fields outside the paramount site of Hindu pilgrimage: Varanasi, a temple town that curls around the Ganges, the equivalent of Rome or Jerusalem in the Hindu imagination. But the pilgrims on my flight from South Korea had an altogether different purpose. It was here, scarcely 15 miles from the airport, among fields now yellow with mustard flowers, that a renunciant prince had, upon gaining enlightenment some 25 centuries ago, given his first sermon, setting what Buddhists call the Wheel of Dharma into motion. At a deer park once called Isipatana, now Sarnath, a 35-year-old Gautama Buddha, hardly older than Christ when he climbed the hill of Calvary, revealed the eightfold path to liberation from suffering, his four noble truths and the doctrine of the impermanence of everything, including the Self. It was to the remains of the monastery and shrine at Sarnath that the pilgrims from East and Southeast Asia came, as pilgrims had for well over 1,500 years, along a subsidiary branch of the Great Silk Road, which ran through the high snowy mountains that girdle the Indian subcontinent into a riverine plain that stretches across what is today Pakistan and north India. The pilgrims took an exit off that highway of goods and ideas that ran from China to Rome in order to honor what may well have been the most influential doctrine to travel along its lines of transmission — the word of the Buddha, and the art made in his name.

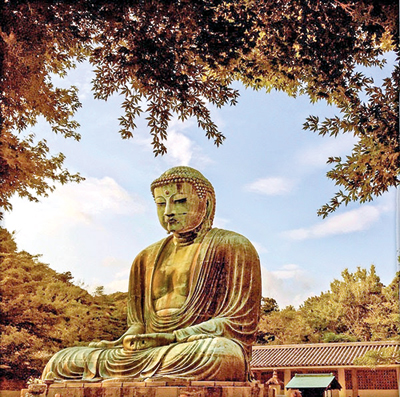

The Great Buddha of Kotoku-in, a Buddhist temple in Kamakura, Japan. The bronze statue, just over 43 feet tall, was likely erected in A.D. 1252, in the Kamakura period.Daibutsu, Kotoku-In Temple, Kamakura, Japan, Thomas Kierok/LAIF/Redux

FOR THE FIRST six centuries after his death, the Buddha was never depicted in human form. He was only ever represented aniconically by a sacred synecdoche — his footprints, for example; or a parasol, an auspicious mark of kingship and spirituality; or the Wisdom Tree, also known as the Bodhi Tree, under which he gained enlightenment. How did the image of the Buddha enter the world of men? How does one give a human face to god, especially to he who was never meant to be a god nor ever said one word about god? How, in rendering such a man in human form, does one counterintuitively end up creating an object of deification? And what is the power of such an object?

These were the questions that were uppermost in my mind as I drove to Sarnath among green fields whose red brick boundary walls advertised educational courses and aphrodisiacs. To pass through open country in India, surrounded by signs of every religion except Buddhism, from temples and mosques to churches and Sikh gurdwaras, was to feel the ghostly imprint that Buddhism had left in the land of the Buddha. Gautama, believed to have been born in the fifth century B.C., had lived and taught the entire duration of his 80-year life within 200 miles of where I was. His doctrine, partly a reaction to the rigidity of Vedic religion, or Brahmanism — widely seen in India as an early form of Hinduism — had flourished here for more than a thousand years, patronized and disseminated by kings.

India’s oldest stone architecture was Buddhist. There had been viharas, or monasteries, that stretched across the Indian mainland, from Sarnath in the north to Nagapattinam, deep in the southern state of Tamil Nadu. There were the glorious painted caves at Ajanta, in western India, and, most intact and enchanting of all, there was the great stupa at Sanchi, in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh. The hemispherical stupa, among the earliest and most distinctive of Buddhist monuments, is a reliquary mound. With its origins in pre-Buddhist burial mounds or sacred tumuli, it retains a cosmogonic power. “The act of making the stupa,” writes Richard Lannoy in his 2001 history “Benares: A World Within a World,” “was a rite in itself, on the analogy of creating the world ‘in the beginning,’ a symbolic re-enactment to get into the right relationship with the source of the Cosmic Order.”

A 14th-century Tibetan painting on cloth of Bhaisajyaguru, or the Medicine Buddha, who is typically depicted with blue skin and holding an apothecary’s gallipot.Medicine Buddha (Thangka), circa 14th century, pigment on cloth, Tibet, Kate S. Buckingham Fund/Bridgeman Images

A 14th-century Tibetan painting on cloth of Bhaisajyaguru, or the Medicine Buddha, who is typically depicted with blue skin and holding an apothecary’s gallipot. Medicine Buddha (Thangka), circa 14th century, pigment on cloth, Tibet, Kate S. Buckingham Fund/Bridgeman Images

The remains of stupas and viharas are scattered all across India, including at Sarnath, but Buddhism, as a religion (though curiously not as a philosophical doctrine) left this land hundreds of years ago. “If Buddhist philosophy is alive anywhere, it is still in India,” P.K. Mukhopadhyay, a philosopher in Varanasi, told me as I was researching my 2019 book “The Twice-Born: Life and Death on the Ganges.” I had studied Buddhist writers, philosophers and poets as naturally as a student of Christianity would move between Old and New Testaments. But when it came to worship, it was an inarguable fact that just as the majority of those for whom Christ was the son of God lived outside the theater of his activities, the Holy Land, so too did the majority of those for whom the message of the Buddha was gospel live beyond the borders of India. This is the world’s fourth-largest religion, with over half a billion adherents — about 245 million of whom live in China alone — but of which only 1.8 percent still live in the land of the Buddha.

MANY EXPLANATIONS have been given for why Buddhism vanished from India. Some say its core teaching was absorbed into a resurgent Hindu faith — in one major branch of modern Hinduism, the Buddha is seen, somewhat controversially, as an incarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu — while others suggest that Buddhism grew too insulated and doctrinal. Mukhopadhyay gave me yet a different explanation: “Buddhism did not have the social support,” he said, suggesting that it was only ever a court religion, and “regal support and social support are not the same thing.” By the seventh century A.D., Buddhism had declined in India before the Islamic invasions of the 12th century dealt its universities and places of worship a devastating blow. The memory of the Buddha, however, lived on in the hearts and minds of Indians. They reacted to him as I imagine the residents of Memphis must react to those visitors to Graceland for whom Elvis is God — pleased that he was a local son but alarmed by the ardor of his followers.

That did not stop multitudes of peddlers, hawkers, hoteliers and day-trippers from chaffering about Sarnath, which was full to overflowing. I picked my way through the low-lying slabs of Buddhist foundations, their red brick now black with time. The fragments of ruins lay all around me, here a splendid amalaka (or notched capping stone from a votive shrine), there, peering out from behind a tangle of steel wire, the smooth unadorned remains of a Buddhist railing, the ancient stone balustrades that formed a perimeter around the stupa, breathtakingly modern in the simplicity of their lines. Ahead, set among manicured hedges and neat flower beds, were the eroded remains of the Dhamek stupa.

We know from two highly detailed accounts by the Chinese monks Faxian and Xuanzang, who visited Sarnath in the beginning of the fifth century A.D. and the middle of the seventh, respectively, that this had once been a vast monastery complex composed of hundreds of sacred monuments, where, according to Xuanzang, no fewer than 3,000 monks lived and taught. Opposite the stupa, he had seen a mighty column “of blue color, bright as a mirror.” The base of the stupa today, 93 feet in diameter, still conveyed solidity and strength, but its top half was worn down to a brick drum, hardly more impressive than the kilns that dotted the countryside in these parts.

A 19th-century Burmese illustration on parchment paper depicting the Buddha seated in padmasana, or lotus position.Bridgeman Images

To gaze up at the empty niches in its eight projecting faces, which scholars believe once held statues of the Buddha, long since destroyed or plundered, was to be reminded of how powerful an absence this figure could leave. The image of the Buddha, with all its iterations, from India to Japan, variant yet somehow changeless, is so literally iconic that we forget that the business of giving a face, let alone a human face, to divinity is fraught with anxiety.

The history of religious art, from Byzantine iconoclasm to Islam’s horror at representing any aspect of God’s creation, is replete with examples of how provocative such an act was. In the case of Buddhism, the provocation was twofold: Early Buddhists did not regard the Buddha as a divine being but a great teacher. He could not be deified for the simple reason that although Buddhism, unlike Jainism — another doctrine, which emerged at the time of Buddhism, as a reaction to Brahmanic orthodoxy — is not actively nontheistic, it is so reticent on the subject of god as to virtually eschew him.

The other problem with representing the Buddha in human form, as the great Sri Lankan art historian Ananda K. Coomaraswamy points out in his 1918 essay “Buddhist Primitives,” is that early Buddhism was disdainful of art itself. He writes: “The arts were looked upon as physical luxuries and loveliness a snare.” Quoting the Dasa Dhamma Sutta, an early Buddhist text, Coomaraswamy adds: “Beauty is nothing to me, neither the beauty of the body nor that that comes of dress.” The relationship between religious and artistic expression is profound, but the evolution of one does not always coincide with the other. Before the early Buddhists found an aesthetic language of their own, they had to rely on a pre-Buddhist lexicon, no less than early Christianity had to borrow from Greece and Rome. In the case of the early Buddhists, the austerity of their doctrine stood in marked contrast to existing forms of non-Buddhist art in India, which were an expression of what Coomaraswamy calls “the Indian lyric spirit.”

Early Buddhism, with all its severity, sought utterance against the background of Vedic religion. The Indian, non-Buddhist art of the time, with its cults of nature and worship of the elements, was in many ways antithetical to the Buddhist spirit. At Sanchi, one sees the strangest of all amalgams: the unornamented Buddhist railing and the spartan simplicity of the stupa competing for space in an overwhelming richness, a world populated by sensuous yakshinis, or dryads, leaning out of ornate brackets, like caryatids, along with drum-bellied dwarfs and the Guardians of the Four Quarters. The stupa, with all its primordial power, sits behind an ornate gateway, or torana, whose sculpted beams undulate, their playfulness culminating in whorled volutes, reminiscent of Ionic capitals.

Sanchi represents a fascinating interplay of the pagan and the puritan spirit. The only real expression of the “intellectual and austere enthusiasm” of early Buddhism at Sanchi, Coomaraswamy felt, was the refusal to show the great teacher in human form. “In the omission of the figure of the Buddha,” writes Coomaraswamy, “the Early Buddhist art is truly Buddhist: For the rest, it is an art about Buddhism, rather than Buddhist art.”

Various stone and bronze Buddha heads, clockwise from top left: from Gandhara, in the Peshawar basin in modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan, produced during the Kushan dynasty, between the third and fifth centuries A.D.; from Angkor, Cambodia, made during the Khmer Empire in the 12th century; from Cambodia or Vietnam, created around the fifth or sixth century; from Thailand’s Ayutthaya kingdom, fabricated between the 15th and 16th centuries.Clockwise from top left: Head of Buddha, circa third-fifth century, schist, Gandhara, India, V&A Images/Art Resource, N.Y.; Head of Buddha, Khmer, 12th Century, Museìe des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet, Paris, Erich Lessing/Art Resource, N.Y.; Head of Buddha, fifth-sixth century, sandstone, Cambodia or Vietnam, Museìe des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet, Paris, Photo: Thierry Ollivier ©RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, N.Y.; Head of Buddha, 15th-16th century, bronze, Ayuthaya, Thailand, Museìe des Arts Asiatiques-Guimet, Paris © RMN-Grand Palais/Art Resource, N.Y.

THE STORY OF how the image of Buddha finally broke forth into the world after 600 years of symbolism is one of the most intriguing in the history of art — one that is inextricably tied up with the advent of a new dynasty in India that, unconstrained by the conventions of the past, was able to set the image of the Buddha free into the world of men.

It begins with the Kushans, descendants of pastoral nomads who emerged like a wind out of the Eastern steppe around the second century B.C. They were heirs to a dazzling hybridity, which included the first ever confluence of Greece, China, Persia and India. Evidence suggests that it was under their reign that a reconstituted form of Buddhism, known as Mahayana (Great Vehicle) Buddhism, flourished and was transmitted along Kushan-controlled trade routes, deep into the East, through China, and eventually Korea and Japan. It was this rare meeting of politics and faith that led to the discovery, Coomaraswamy felt, “that the two worlds of spiritual purity and sensuous delight need not, and perhaps ultimately cannot, be divided.”

It is something of a miracle that the Kushans should ever have existed. Their progenitors, the Yuezhi, nomads who roamed the pastoral grasslands of modern-day Gansu, had been pushed out of China in the second century B.C. The Yuezhi drifted into northern Bactria, modern-day Afghanistan, which at the time was controlled by Greek kings, the residue of Alexander the Great’s conquest. The Indo-Greeks lived in garrison towns that turned into cities, and numismatic evidence shows Demetrius I, who reigned in Bactria from about 200 B.C. to 180 B.C., wearing an elephant scalp as a symbol of his conquest of India. His successors, such as Menander I, converted to Buddhism and extended their kingdom deep into the Gangetic plain. It was this India, one fertilized by Greece, that the Yuezhi, now Kushans, inherited. Led by the marvelously named Kujula Kadphises, they conquered Greek Bactria in the first century A.D. That conquest, writes Craig Benjamin in “Empires of Ancient Eurasia,” his 2018 study of the first Silk Roads era, which he dates from 100 B.C. to A.D. 250, “was the very first incident ever in world history that was commented upon by both Western (as in Greco-Roman) and Eastern (as in Chinese) historians.” The Kushans, as if racing to meet their destiny as the bridge between East and West, would go on to become the quintessential Silk Road empire.

A painting of a multitude of sitting Buddhas on the walls of Ajanta, the caves of Maharashtra, India. Believed to have been created between the first and second centuries B.C. and the fifth century A.D., the caves are one of the oldest Buddhist sites in the world.Bridgeman Images

Various stone and bronze Buddha heads

The Kushans had come into a world that was already in flux. The rise of the Achaemenids in Persia around the time of the Buddha had produced the first truly global empire. Gautama’s own semi-independent tribal state of the Shakyas, on the border of India and Nepal, with its capital at Kapilavastu, was less remote than we imagine. “The Uttarapatha,” or the great northern trade route, writes Lannoy, “linked the rich iron and copper deposits of the eastern Ganges region with the civilization of western Asia, bringing wealth to the merchants of Kapilavastu.” This was a time described by the 20th-century German philosopher Karl Jaspers as the Axial Age. The stasis of localized cults and religions was giving way to the pressures of a new internationalism. It was no accident that the Buddha, with his universalizing meditation on the human condition, appeared at the same time as Heraclitus in Greece and the Taoist teacher Lao Tzu in China.

Everywhere, across what was not yet the Silk Road, old enclosed societies were being changed by a new awareness of the world beyond. The Achaemenids had waged war with Greece, inadvertently exciting the future ambitions of Alexander the Great. In the wake of Alexander came the first centralized Indian state, the Maurya Empire, their founder known as Sandrocottus to the Greeks, Chandragupta Maurya to the Indians. The support shown by Chandragupta’s grandson, Ashoka, of Buddhism in the third century B.C. had an electrifying effect on the fortunes of the new religion, not unlike that of Constantine’s conversion to Christianity. It was Ashoka who is said to have erected the column of dazzling blue that Xuanzang saw at Sarnath in the seventh century A.D., and to have spread Buddhism in both India and Sri Lanka: Legend has it that he sent a mission led by his son and daughter, both carrying a branch of the Wisdom Tree and thus, Lannoy writes, “literally planting Buddhism in the soil of Sri Lanka.” But it was the Kushans who turned Buddhism from a local Indian cult into a world religion.

A GREAT PART of the Kushans’ success lay in their receptiveness to the cultural influences around them. They displayed an extraordinary ability to assimilate and absorb the four major civilizations they encountered, turning syncretism, or the creative mixing of culture (in this case from Persia, India, Greece and China), into something of a competitive sport. In order to make a cohesive whole of their empire, which would come to look like a giant amoebic blob at the crossroads of four discrete civilizations — with one arm reaching deep into Central Asia, the other outstretched, as if in a game of Twister, into the very bosom of the Gangetic plain — the Kushans showed a willingness to sacrifice their own identity in order to meet the cultural demands of the world they had inherited. In place of their spoken tongue, Tocharian, the Kushans adopted Bactrian, which they called the “Aryan language,” as the court language in what Benjamin sees as “part of an intentional policy change by the Kushan leadership.” Bactrian, with its middle Iranian roots, gave the Kushans influence in the region, even as their use of Greek letters spoke of continuity with the past. To add to this dizzying hybridity, the Kushans adopted Buddhism, part of their ethos of tolerance, which also included the veneration of Greek, Indian and Zoroastrian deities.

A Tang-era painting made by Chang Huai-hsing in A.D. 897 depicting a golden Buddha surrounded by five planets: Mercury, Venus, Jupiter, Mars and Saturn.Tejaprabha Buddha and the Five Planets by Chang Huai-Hsing, Art Collection 4/Alamy

The greatest of all Kushan kings was Kanishka, great-grandson of Kujula Kadphises, and to look upon his headless statue from the first centuries A.D., now in terribly reduced circumstances at the shabby Government Museum in Mathura, 115 miles southeast of New Delhi, is to feel as profound a sense of cultural dislocation as I have ever known. He is made of red Mathura sandstone but dressed in nomadic riding boots, redolent of the steppe. Like a Rosetta Stone of statuary, it is possible to see in him the wild hybridity that coalesced in this region during the first century. He holds a sword and mace, and across his long cloak, the inscription in middle Brahmi, an ancient Indian script, now extinct, reads: “The Great King, King of Kings, Son of a God, Kanishka.”

It was on coins issued by this museum-quality narcissist that we see some of the earliest images of the Buddha in human form. Was Kanishka aware of doing something that had never been done before? Was he merely mass-producing an image that had privately already entered human form as a cult object? Was the depiction of the Buddha as a human being the legacy of Greek influence in Bactria, or was there, as Coomaraswamy believes, a now lost origin story of the first Buddha in India, which was then adapted by Greek-trained craftsmen? These are the questions that swirl around this enigmatic moment in the history of art.

The clearest answers lie in the fact that the Kushans would go on to establish two great centers of statuary. One was Gandhara, a region that stretches across modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan, and where the statues are of an ashen schist and bear the unmistakable mark of Hellenism, almost as if a bunch of Buddhas and bodhisattvas had showed up at a toga party. The other school — one I like more, for being less derivative — was Mathura, where craftsmen worked with a white-speckled russet stone. These Buddhas, unlike those of Gandhara, are of fuller body, with soft Indian bellies. They look less vain and haughty than the Gandhara Buddhas, and their faces possess a deep sympathy — that hint of a smile, as sorrowful and knowing an emotion as has ever been expressed in stone.

From these two great workshops some of the earliest Buddhas burst forth into the world. “This new physical representation,” writes Benjamin, “helped the ideology of Buddhism transform itself into a religion and spread along the trade routes as far south as Sri Lanka and as far east as Korea and Japan.” It was an image that adjusted itself to the places it traveled to, from Cambodia and Korea to Indonesia and Nepal, but the underlying thought the image expressed spoke more of continuity than difference, just as the image of Christ on the cross is a unifying one, despite its varied iterations. In addition to the mass production of Buddha’s self, historical Asian texts indicate that Kanishka’s reign also saw the widespread construction of monasteries and stupas, the convening of a major Buddhist conference in Kashmir and the large-scale translation of Buddhist texts into Sanskrit, which served the newly reconstituted religion as a major lingua franca.

The Great Buddha of Kotoku-in, a Buddhist temple in Kamakura, Japan. The bronze statue, just over 43 feet tall, was likely erected in A.D. 1252, in the Kamakura period.Daibutsu, Kotoku-In Temple, Kamakura, Japan, Thomas Kierok/LAIF/Redux

Kanishka, Benjamin tells us, is recognized in Chinese sources as “a great patron of Buddhism.” His reign, which coincided with that of the Later Han emperor Mingdi, saw the establishment of the first Buddhist temple in China, the White Horse Temple near Luoyang. In A.D. 166, the Han emperor Huandi honored the Buddha with a sacrifice and, “during the two centuries that followed the collapse of the Han,” writes Benjamin, “much of the population of northern China adopted Buddhism, and by the sixth century the ideology had spread widely throughout southern China as well.” Just as Buddhism had been a reaction to the hierarchical nature of Brahmin orthodoxy in India, so too in China, Benjamin feels, the Chinese warlords, who had felt disparaged by Confucianism, were attracted to the “egalitarian creed.” Monks, such as Kumarajiva, who was from Central Asia and active in the fourth century B.C., played a key role in translating Buddhist texts into Chinese. This, in turn, excited the curiosity of men like Faxian and Xuanzuang, who flocked to India. These monks — not unlike the great book hunters of the Renaissance, such as Poggio Bracciolini, who in the 15th century discovered Lucretius’s “De Rerum Natura,” the classical poem that played so key a role in the intellectual rebirth of Europe — were primarily in search of manuscripts, philosophical treatises and biographical information about the life and times of the Buddha. The traffic of monks and scholars between India and China lasted well until the 12th century, when Muhammad bin Bakhtiyar Khalji, a Turkic chieftain, destroyed the great Buddhist university of Nalanda, in what is today the eastern Indian state of Bihar.

AT SARNATH, STANDING at the base of the Dhamek stupa, a giant embroidered band of sculpture, geometric designs and verdure wrapped around its midriff, I was reminded of the power of the image of the Buddha. Sacred images in ancient India were not made primarily as objects of beauty but rather as the expression of a philosophical thought, which is why the same image was made again and again. The Swiss artist and scholar Alice Boner, who lived in Varanasi from the 1930s until just before her death in 1981, cautioned against treating these images as mere objects of “aesthetic enjoyment.” They were visual aids, “born in meditation and inner realization.” Their ultimate aim, as “focusing points for the spirit,” was to lead us “back to meditation and to the comprehension of that transcendent reality from which they were born. If they are beautiful,” Boner adds, taking a swipe at modern aesthetic notions, such as art for art’s sake, “it is because they are true.”

The Buddha, seated in padmasana, or the lotus position, with his legs crossed under him, hands open-palmed in his lap, his face a mask of smiling sagacity and fierce inwardness, was certainly beautiful, but he was also a perfect articulation of what dhyana, or “meditation,” meant in the Hindu-Buddhist context. I, for one, could not look at the image of the Buddha without being reminded of this description of the Hindu god Shiva from the Sanskrit poet Kalidasa’s fifth-century work “The Birth of Kumara”:

The fierce pupils motionless

and their brightness slightly lessened,

his eyes, directed downward,

were focused on his nose,

the eyelashes stationary,

the stilled eyes stilling the brow.

By restraint of his internal currents

he was like a cloud

without the vehemence of rain,

like an expanse of water

without a ripple,

like a lamp in a windless place,

absolutely still.The story of depicting the Buddha is ultimately one of continuity and rupture. Above all, it is a tale of how newness enters the world. It is also the paradigmatic Silk Road story, for being an inadvertent and quiet assertion of the creative freedom implicit in the meeting of cultures. Nothing is more quintessentially Indian than the image of the Buddha seated in padmasana, but for that quintessence to be unlocked, for thought to enter stone, as it were, a catalyst was needed. That catalyst was the Kushans. Through them, Greece, Persia, India and China bore witness, like godmothers in a fairy tale, to this second birth of the Buddha. Here, too, it seems — in our most inviolable symbols and icons, so pure as to seem without origin — lurks the mongrel spirit of hybridity, full of surprise and audacity, a perpetual thorn in the side of our tribalisms.

Aatish Taseer’s latest book, “The Twice-Born: Life and Death on the Ganges” (2019), was recently released in paperback. His documentary, “In Search of India’s Soul,” produced by Al Jazeera, is streaming now. He is based in New York City.

If You Go (When It’s Safe to Travel) …

There are many reasons to travel to northern India, including visiting the holy city of Varanasi. For the purposes of exploring early Buddhist history, the great Dhamek Stupa in Sarnath is a must-see, as is the Government Museum in Mathura, home to some of the best sculptural works made during the Kushan Empire. For a more extended trip through the country, the rock-cut Buddhist caves of Ajanta, in Maharashtra, are also a sight to behold.

(Courtesy the New York Times Magazine)

| When it’s safe to travel … | |

| There are many reasons to travel to northern India, including visiting the holy city of Varanasi. For the purposes of exploring early Buddhist history, the great Dhamek Stupa in Sarnath is a must-see, as is the Government Museum in Mathura, home to some of the best sculptural works made during the Kushan Empire. For a more extended trip through the country, the rock-cut Buddhist caves of Ajanta, in Maharashtra, are also a sight to behold. |