News

Storm over sand nourishment

Mount Lavinia. Pix by M.A. Pushpa Kumara

Independent experts have slammed the Coast Conservation Department’s (CCD) hurried “beach nourishment” initiative in Mount Lavinia saying it was ill-planned, unnecessary and ineffective.

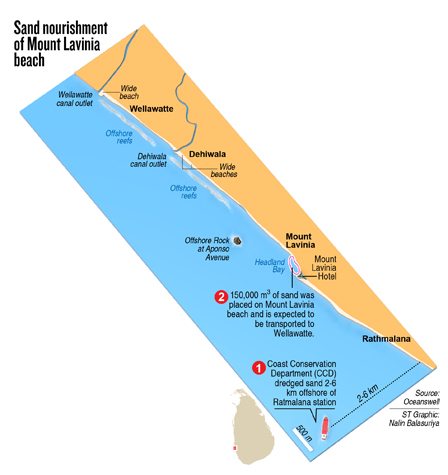

The CCD claimed this week that the ‘Artificial Soft Beach Nourishment Project’ was a success and will prevent erosion along the coast from Mount Lavinia to Kalutara. A total of 150,000 cubic metres of sand was dumped on Mount Lavinia beach in the expectation that it will drift northwards with the currents and create a 15m stretch of beach at Wellawatte.

“The sand nourishment of Mount Lavinia beach appears to have no tangible outcomes with respect to the aims of the project,” argues a report titled ‘The Tragedy of Mount Lavinia Beach’ released this week. “The exercise appears to be undertaken without adequate planning and ignoring even basic coastal engineering principles. However, a considerable amount of money has been spent.”

Professor of Coastal Oceanography Charitha Pattiarachchi, Marine Biologist Asha de Vos and Nadiya Azmy, a Programme Officer at Oceanswell, jointly wrote the report. A majority of the sand will be washed away from Mount Lavinia beach after the South-West monsoon, through design or otherwise, they forecast.

Professor of Coastal Oceanography Charitha Pattiarachchi, Marine Biologist Asha de Vos and Nadiya Azmy, a Programme Officer at Oceanswell, jointly wrote the report. A majority of the sand will be washed away from Mount Lavinia beach after the South-West monsoon, through design or otherwise, they forecast.

Some of the sand was already removed by higher energy waves caused by Amphan, the tropical cyclone. The percentage of sand deposited at Mount Lavinia beach making it as far as Wellawatte “is likely to be small and certainly not sufficient to create the anticipated 15m beach”.

The implementation of the project also did not fit the “sand engine” method which the CCD claims to have used, said Channa Fernando, a coastal/harbour engineering and environmental expert. This technique envisages the use of waves, winds and currents to move sand along the shoreline, adding it to areas that are eroded. To facilitate this, a large stockpile of sand is artificially deposited on the up-drift side and is expected–generally over 10 years or more–to move downwards along the shore.

“I think beach nourishment carried out at Mount Lavinia is far behind in meeting the sand engine concept,” Mr Fernando said. The general technique in distributing nourished sand along the shoreline has, however, been followed.

“Firstly, nowhere is it mentioned of the intended influence area of the sand engine method,” he observed. “By chance, Wellawatte was found as the limit. Why was it not extended beyond Wellawatte towards Bambalapitiya or Kollupitiya?”

Angulana

“Secondly, there is no reported evidence of nourished beach areas between Mount Lavinia and Wellawatte,” he continued. “Thirdly, if it was meant to create an up-drift stockpile in Mount Lavinia, that stockpile has only lasted for few weeks rather than 10 to 15 years.”

For it to be successful in distributing the sand, however, the beaches must be relatively free of any obstructions to it being moved down-drift by natural forces.

“But there are natural and artificial obstructions such as a natural near-shore rock patch at Dehiwala and Dehiwala Canal sea outfall,” he said. “The Dehiwala canal outfall is generally blocked by sand barriers during the drier months of the year and there is no major environmental issue as flow in the Dehiwala canal is also very low.”

It was possible that sand will now accumulate at the Dehiwala outfall. “Luckily, heavy rains in Colombo after the beach nourishment caused high flows in the canal, preventing the deposition of the northward moving sand at the outfall mouth,” he said.

Wellawatte

Prof Pattiarachchi and his team also said their analysis identified several natural and man-made barriers for northward sand transport between Mount Lavinia and Wellawatte. These include the rock structure at Aponso Avenue and the canal outlets at Dehiwala and Wellawatte.

“There is no indication of how much sand will bypass these obstructions and whether the siltation as a result of increased sand supply will impact these outlets,” they state. “It is possible that additional dredging may be required to keep the canal outlets open.”

The sand was placed on the exposed beach and moulded onto the beach shape by earth-moving vehicles, they also point out: “If the aim was for the sand to supply Wellawatte, it makes little sense to place the sand on the beach. Rather sand placed just off the beach, below the water level would have been a much more efficient and less expensive means of achieving said goal.”

Ratmalana

It would have been better for the project to have been undertaken avoiding the South-West monsoon period, Mr Fernando said. Then, moderate sea forces would have allowed more time for sand to move and stabilize along the nourishing beach stretches. “However, that does not mean that the erosion that we have experienced could have been totally avoided,” he said.

It is clear that there has been no erosion in the five kilometre stretch between the Mount Lavinia headland and Wellawatte canal outlet, Prof Pattiarachchi’s report even states: “It has been stable for many decades.” There was only a natural variability in the beach resulting from seasonal changes.

To design a sand nourishment project, detailed investigations are usually carried out to define outcomes. The CCD has indicated its aim was to create a 15m wide beach at Wellawatte, five kilometers away from Mount Lavinia where the sand was dumped.

“In this situation, it is imperative to define a sand budget for the study area which then allows for calculating the volume of sand that is required for nourishment and where to place that sand,” the report explains. “There is no record that any of these studies were undertaken as evidenced by a lack of an EIA [environmental impact assessment] for the sand nourishment.” The EIA was done only to dredge the sand from offshore Ratmalana.

Kalutara. Pic by S. Siriwardene

In general, in sand nourishment projects, it is expected that a volume of sand equivalent to two to three times the amount that is nourished is ‘lost’ from the system, the report says. So placing 150,000 cubic metres “was a gross underestimate and therefore it is not surprising that the sand was taken away from the beach”.

The beach stretch immediately north of Mount Lavinia Hotel, about 250m towards the North, cannot be protected with nourished sand without combining it with a structural intervention due to the highly turbulent wave forces prevalent at the locality and the wave diffraction, Mr Fernando opined.

“Even during the calm or off-monsoon period, one could hardly find much sand in this beach stretch, while rest of the areas northward could experience beach build up in the off monsoon period,” he asserted. “However, a substantial volume of sand had been pumped in this short stretch, even extending beyond the Mount headland point.”

“All this sand has disappeared due to wave diffraction and highly turbulent wave forces at the locality,” he said. “This loss of sand is very prominent, as most of the photos published in the media included the current situation and what it was soon after the nourishment. How much of this sand would return to the shore during the calm period is yet to be seen.”