Less food from more agriculture!

View(s):

File picture of a vegetable farmer with an agriculture extension officer.

Many years ago, I was connected to a research project of the Integrated Rural Development Programme (IRDP) in the Monaragala district. The research project which was led by Dr. Wilbert Gooneratne, a former regional development expert of the United Nations Centre for Regional Development (UNCRD).

When we passed through Wellawaya and Buttala to reach Monaragala, it was a usual seasonal scene to observe lime fruits piled up from place to place on the roadside. The people living on either side of the road wanted to sell limes to the vehicles that pass by, so they bring them up to the road and pile them up there. The price was cheap at Rs. 5 a kilo because of excess supply. Traders were not interested in buying lime unlike other stuff. It is not surprising that even the travellers didn’t want to buy so much lime even if they were sold so cheap. Obviously, what are you going to do with kilos of lime, when you need just half a lime fruit for your occasional coconut sambal?

I remember that we began to wonder why people had grown so much lime, when there was no such a big market for them. Later, we came to know that it was a result of a “development project” under which lime plants were distributed among the villages some time ago. But the project planners had never planned what to do with lime, when the trees begin to bear fruits.

Monaragala was an interesting location that had attracted many development projects of the government agencies and non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and for that matter many research projects too. But I didn’t see much evidence to answer the question as to how a location can be developed in “isolation”.

Go out in the weekends

At that time, one of our colleagues – Dr. Rupananda Widanage, who is now working at the University of Hawaii in the US, carried out a research on “food security” in the Monaragala district. Food security is simply the guaranteed availability of enough food for the family. Isn’t it a strange idea to do a research on food security of the people engaged in agriculture? Monaragala district is, anyway, an agricultural area even to-date with abundant agricultural land so that what’s the point of testing the farmer family’s food security there? Some of us might ask that question. Nevertheless, the puzzle is that food security is strongly connected to poverty and, poverty in Sri Lanka is very much a problem in the rural agricultural sector. And after all, Monaragala is not only an agricultural area but also a poor area in the country.

According to the most recent poverty data, 5.8 per cent of people in the Monaragala district and 6.5 per cent of people in the Uva province are poor, compared to 4.1 per cent – the national average of Sri Lanka. Agriculture share of provincial GDP is 13 per cent in the Uva province, compared with its 8 per cent share to national GDP.

Educated people don’t find much to do in such poor and agriculture-dominated areas such as Monaragala. Naturally, they move to Colombo as well as to other developed provincial cities such as Galle and Kandy. Industry and service sectors still have a long way to progress in order to accommodate higher levels of skilled labour.

Friday afternoon public buses departing from Monaragala especially to Matara are unusually crowded. School children had to leave Monaragala to attend the weekend tuition classes in Matara. Some of them had even their weekend lodging arranged in Matara so that they could come back on Sunday evening after attending the tuition classes. Some of the children from affluent families were not even in their schools, as they were in Colombo throughout the week attending tuition classes.

Together with school children, many of the public sector officials working in Monaragala were also leaving the area for the weekend. It is because many of them were from outside Monaragala so that in the weekend they too go home. Even if they choose to stay in Monaragala, there was nothing you can do there during the weekends.

More agriculture, less food

Findings of the research on food security were weird, after all. The research findings showed that it was basically the level of income rather than agriculture that guaranteed food security. Even in the case of agriculture, the families which were dependent on growing the cash crop “sugar cane” had better food security than those who grow subsidiary crops. It was a surprise that subsidiary food crop growing families usually face “chronic and transitory food insecurity” due to their low incomes.

Further, sugar cane growers were “self-reliant” which means they can take care of themselves without depending on external support – primarily, the government support. But they were not “self-sufficient” which means they don’t grow everything they want for their food on the table. On the contrary, subsidiary crop growers were self-sufficient, but not self-reliant. They depended more on government assistance.

It is indeed strange that agriculture is fundamental to food security, but food security does not depend on agriculture. Somebody might raise a logical question here asking that “then, if everybody leaves food crop cultivation, does it lead to higher food security for the nation?” Even though, some of us would be quick to say that “then, there would be no food at all”

It is indeed strange that agriculture is fundamental to food security, but food security does not depend on agriculture. Somebody might raise a logical question here asking that “then, if everybody leaves food crop cultivation, does it lead to higher food security for the nation?” Even though, some of us would be quick to say that “then, there would be no food at all”

Economists call such issues as “fallacy of composition” – the error of thinking what is true for parts of a whole is true for the whole as well. Even though there is fallacy of composition issue for thinking that what is correct for Monaragala is correct for the entire country, we shouldn’t jump into an answer like that. Let’s look at the issue in an international context.

Food security ranking

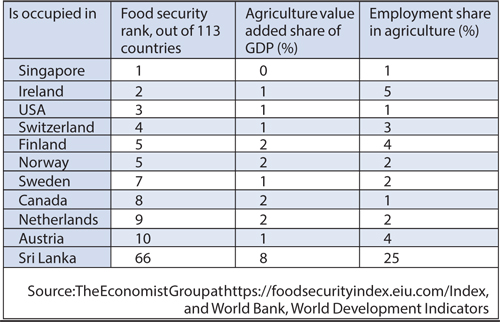

Global food security is defined on the basis of three indicators, namely the (a) affordability of food, (b) the availability of food and, (c) the quality and safety of food. When the food security is measured for 113 countries in the world, the number one is Singapore which has near zero contribution to its GDP. Together with Singapore, the other countries among the top-10 are Ireland, the US, Switzerland, Finland, Norway, Sweden, Canada, Netherlands and Austria. They all produce 1 to 2 per cent of agriculture contribution to their GDP.

Having being classified as the 66th ranking position among all the countries surveyed, Sri Lanka is not even among the first half of the countries. Among the top-10 countries, less than 5 per cent of the labour force is occupied in agriculture, whereas in Sri Lanka a quarter of our labour force is in agriculture. The world experience suggests that having an agriculture sector that dominates production and employment does not lead to higher food security.

Why does a country like Singapore having near zero agriculture share in GDP come on the top of food security? It is because having high income non-agriculture, Singaporeans can afford to buy the food in best quality, which is produced by other countries. Just like that, some of us in Colombo say that people in rural areas should grow food crops so that our food security is guaranteed, but not that of the farmers. And they also make sure that their children should never go to work in rural agriculture. .

(The writer is a Professor of Economics at the University of Colombo and can be reached at sirimal@econ.cmb.ac.lk).