Jobless graduates

View(s): A few weeks ago, I was invited to speak on the “employability of university graduates” at a workshop for the junior university lecturers. Together with me, Manjula De Silva, General Secretary and CEO of the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce had also been invited to speak as a resource person representing the business sector.

A few weeks ago, I was invited to speak on the “employability of university graduates” at a workshop for the junior university lecturers. Together with me, Manjula De Silva, General Secretary and CEO of the Ceylon Chamber of Commerce had also been invited to speak as a resource person representing the business sector.

Since our universities have a long-standing fame for producing “unemployable graduates” and this puts myself in the dock too in my capacity as a university professor, the speech was a challenge for me.

Confirming my thoughts and explaining about this matter to a friend of mine, he first laughed, and then, commented: “So, you may have to speak about your own profession and about your own colleagues?”

I didn’t defend myself against what he implied: “Well, if unemployable graduates are a product of their own university teachers, we must know that these teachers are also a product of the same system; a teacher must also teach what he learnt previously. We are reaping the fruits of a ‘closed university system’ which we have nurtured for more than half a century.”

My friend’s comment did not surprise me. Apparently, it reflects a social and political perception about the “unemployable” graduates who magnify it by their own actions. They have even established a “trade union of unemployed graduates” and engaged in frequent demonstrations and protests demanding jobs. To make matter even worse, they were often at the mercy of the government which continued to be the main job provider for unemployed graduates throughout the history.

Half of the problem

At the outset of my speech, I posed a question: “How many of you think that you and your universities are responsible for producing unemployable graduates?” No one answered, but the smile on their faces confirmed that it was a valid question. Then, I gave my version of the answer: “If the lecturers and universities are responsible for the unemployability problem of graduates, then I must say that their responsibility is limited only to half of the problem”.

The inevitable question is, then “why half of the problem?” It is because “job creation” through investment promotion and economic progress is responsible for the other half. If the jobs are not created, unemployment persists. According to our findings, it is a tiny fraction of the business sector in Sri Lanka that demands for “graduates” to be recruited as employees, while still a large part of our traditional private sector does not need graduates. If the job can be done by recruiting a school leaver with or without secondary educational qualifications, why should they demand a graduate?

Unemployed graduates during a protest on Wednesday near the Presidential Secretariat. Pic by Amila Gamage

Graduates are needed for higher levels of businesses, while if such businesses are not expanding in the country then there is no job creation for the graduates produced by the university system. Even though most of these businesses are in the services sector, it does not exclude manufacturing and agricultural sectors too. For instance, most of the farmers in some of the European countries are graduates who run their agricultural activities as a modern business ventures and engage in intensive research and development activities in their large-scale farms. But Sri Lanka’s small-scale agriculture sector as well as the small and medium enterprises hardly requires graduates.

Therefore, sluggish business progress which is reflected through slower investment expansion, slower economic growth, and slower export promotion explains a significant part of the unemployment problem of the graduates in particular and, educated youth in general. In a country with a dismal economic performance, a typical characteristic is the unemployment of the educated youth.

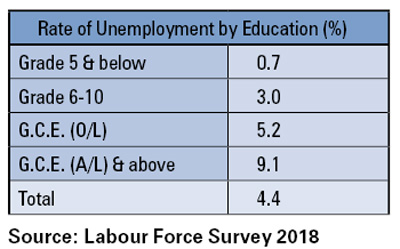

Historically, Sri Lanka has shown that “the higher the level of education, the greater would be the possibility to remain unemployed”, as confirmed by the country’s unemployment statistics. The less-educated people naturally slipped into the unproductive agriculture sector or informal activities, not because they like it but because they don’t have other choices. As the level of education rises, people hardly chose to be in such unproductive sectors, because their aspirations are greater, and they deserve better opportunities. The problem is the lack of job creation to satisfy this need due to inadequate business expansion.

Seeking the same job

The absence of an expanding business environment to absorb graduates has created two major issues. The first is on the demand side: Irrespective of what subjects or in which faculties they have studied, the majority of the graduates compete for the same types of limited number of jobs available in the country. Perhaps, an exception are the graduates from the Faculties of Law, Education, and Medicine because there is a government-guaranteed job market, or these fields are professional by nature. Graduates from all other faculties such as Agriculture, Arts, Commerce, and Science — all compete for the same set of jobs mostly in the areas of the financial sector or public administration.

The second issue is on the supply side: It is the government which continued for decades to provide jobs to the majority of university graduates, again irrespective of their subject areas or the faculty of studies. This was not necessarily because the successive governments needed their service, but because it was a political problem. As the subjects that graduates study in the university bears no relevance to the bulk of jobs offered by the government, it is also irrelevant to many students to pay attention to the question of which subjects they should study.

Even the universities do not have a clue about “how many graduates from each subject area should be educated and trained in order to meet the national requirement for human resources; simply there is no “national requirement” as such. Therefore, the students too are tempted to choose “easier subjects for better results” as their ultimate objective is not necessarily about knowledge and skills in a particular subject area, but the “certificate” that they can carry.

The complain that many private companies made is that even the few graduates that they have recruited and trained, would eventually leave for government jobs even for a lower salary, when the government announces job offerings. Therefore, any effort to recruit and train the graduates is an unnecessary costly affair for the private firms. At the same time, it may be a rational choice for many graduates who prefer less-challenging, pensionable jobs with job security. The problem may continue to remain unless and until there is a balance in the differences in employment conditions between the private sector and the government sector.

Another issue is that the graduates are “too old” to be recruited and trained in a job. In fact, by international educational standards our students stay too long in education in the schools and in the universities so that when they become graduates, they are about four-five years older than their counterparts in other countries.

International educational hub

Even at the universities which are protected from exposure and competition by regulatory barriers, there is no need for forming a globally competitive higher educational system. Our university system is not open to “importing knowledge” by recruiting foreign academics and “exporting knowledge” by catering to foreign demand for higher education. Otherwise, Sri Lanka would have been an “international educational hub” in the region with a set of globally competitive universities earning foreign exchange from teaching and research.

After looking at the problem of the “unemployability of graduates” in Sri Lanka from different angles, it is necessary to raise the question as to “who are the stakeholders of the problem?” As I have attempted to analyse the problem objectively, it is clear that the incompetency of the university system cannot be an issue isolated from the rest of the performance of the economy. The unemployability issue of graduates runs well beyond the premises of a university, encompassing the need for broad-based regulatory reforms.

(The writer is a Professor of Economics at the University of Colombo and can be reached at sirimal@econ.cmb.ac.lk and follow on Twitter @SirimalAshoka).