News

United they fall: What led to the Yahapalana crash

View(s):The Commission of Inquiry (COI) now sitting into last year’s Easter Sunday massacres has seen a blame game publicly exchanged between the former President Maithripala Sirisena and former Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe apportioning responsibility for the incident on the other.

The evidence so far in the public domain has spilled over to sparing of a political nature ranging from name-calling to contempt of each other.

The ruling coalition has not only profited electorally from this public spectacle but also exploited the sharp divisions to showcase the nature of a dysfunctional Cohabitation Government resulting from two power-centres — Parliament (Prime Minister) and the Executive President. Thereby it has used the occasion to blame the 19th Amendment to the Constitution and promote and justify its proposed 20th Amendment that seeks to strengthen one power-centre, the Presidency.

The Sunday Times publishes today extracts of the evidence given before the COI over the past few days by President Sirisena and former PM Wickremesinghe and how the two secretaries of theirs monitored the initial honeymoon between the leaders of the country’s two largest political parties which quickly turned sour and later developed into personal animosity, leading to breaking point of the experimental National Unity Government.

In EXCLUSIVE interviews granted to the Sunday Times, Austin Fernando, onetime Secretary to President Sirisena and Saman Ekanayake, then Secretary to former PM Wickremesinghe speak candidly of the way they saw the work and later the cracks that led to the downfall of the Yahapalana Government of 2015-2019.

“Politics is a dirty game – no one can correct a President”

- There were those who “fertilised” the conflict between Sirisena and Wickremesinghe

- President Sirisena shed powers of his office – can’t see how he can vote for 20A

- Sirisena’s public berating of his PM culminated in souring of their relationship

- A President is only ‘Head of the Executive’ – there are other arms of executive power

By Sandun Jayawardana

“When we heard of it, another person, who was a legal authority of the state, and I went to the President and told him this should not happen,” said Austin Fernando, who was then Presidential Secretary. “We told him that this was against the law and that he will lose in court if his decision was challenged. He listened to us then. I learned that when the coterie who were clamouring to remove the PM came to him again and again pressuring him to act, he told them he had agreed with our reasoning.”

But the conflict between the two grew progressively worse after that. “There were others who fertilised this conflict beautifully,” Mr Fernando said. “In the end, the pressure on him became too great. I was about to leave for New Delhi to take up my appointment and was no longer an adviser to the President. But I watched what was going on.”

In his address to the nation on October 28 that year, after finally sacking the PM, the President said he had obtained legal advice beforehand. The expectation they had was that he would have got the advice from the Attorney General, as he was the official legal adviser to the President and the Government. “But he did not say where the advice came from,” Mr Fernando reflected.

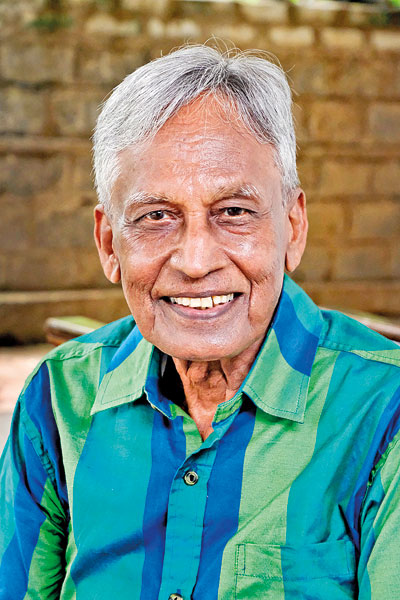

One of Sri Lanka’s longest-serving civil servants, Mr Fernando was Secretary to President Sirisena from July 2017 to July 2018. Before that, he served as Eastern Province Governor and Adviser to the President from 2015 to 2017. His association with Mr Sirisena goes back to 1975. He, therefore, has valuable insight into the former President and the workings of the Yahapalana Administration.

In 1975, Mr Fernando was Additional Government Agent for Polonnaruwa and Mr Sirisena was an SLFP cadre working with Mr Leelaratne Wijesinghe, the party MP for Polonnaruwa. He was just another citizen to Mr Fernando. Later, as Grama Sevaka, Mr Sirisena was his subordinate. When Mr Sirisena, as President, invited Mr Fernando to work for him, the roles were reversed.

Simmering tensions between President Sirisena and Prime Minister Wickremesinghe culminated in the ‘Constitutional Coup’ of October 26, 2018, when President Sirisena sacked his PM overnight one weekend surprising the entire nation, leave alone his Prime Minister and his Cabinet and installed the then Opposition Leader, Mahinda Rajapaksa, as his new Prime Minister. Mr Fernando pointed out how the President had alluded to the reasons during his subsequent address to the nation.

Austin Fernando, ex-Secretary to President Sirisena. Pic by Amila Gamage

President Sirisena said there were so many differences between them (the President and Prime Minister) in terms of culture, personality, behaviour and in policy”. Mr. Fernando says, “I consider this explanation to be valid (grounds for the expulsion of the PM).”

“Mr Wickremesinghe comes from the so-called ‘Colombo 7’ elite circles, while President Sirisena is a former soldier’s son from the colonisation scheme and was a Grama Sevaka,” Mr Fernando said.

“Mr Wickremesinghe is an advocate of the Supreme Court whereas the other person is trained in agriculture and whose educational qualifications are not that great. Mr Wickremesinghe was very fluent in English. Mr Sirisena could understand English but he was not fluent in speaking it.”

“On the other hand, Mr Sirisena could speak for hours in Sinhala without even the slightest mistake, whereas Mr Wickremesinghe was not as fluent in Sinhala as he was in English,” he continued. “President Sirisena started politics with the China wing of the Communist Party. He later became an SLFP member. The SLFP was a socialist-oriented democratic political party, whereas Ranil Wickremesinghe hails from the same family as President J.R. Jayewardene, who was called ‘Yankie Dickie’ (for his pro-US stance). The party he represents is said to be more capitalist than any other party. All those things mattered in their relationships.”

Mr Sirisena was roundly criticised for taking up the SLFP leadership after contesting the Presidential election as the common candidate. Mr Wickremesinghe once remarked that this was when he started distancing himself from the United National Party (UNP) and others that worked for the common candidate’s victory.

Mr Fernando, however, said Mr Sirisena could not be blamed for choosing to establish a political identity. “You can’t tell a politician to forget about their party and their identity,” he pointed out. “He is a politician. And a politician must have a political identity. History has shown this is important to a politician.”

But Mr. Fernando acknowledged that taking up the SLFP leadership compelled President Sirisena to make uncomfortable decisions. For instance, he had to give Cabinet positions to some SLFP members who worked against him at the Presidential election (and later crossed over to the Yahapalana government).

The President also failed in his pledge to abolish the Executive Presidency. He had made a solemn pledge to do so before the Presidential election. (He later went around the world saying he was the only President in the world who had voluntarily sacrificed his powers through the 19th Amendment to the Constitution). Both, Presidents Chandrika Kumaratunga and Mahinda Rajapaksa had made the same promise before, only to renege on it later, Mr Fernando said.

However, as a non-lawyer and layman, Mr Fernando felt executive power was not the monopoly of the President. Article 4 of the Constitution states it’s the “executive power of the people,” including the defence of Sri Lanka, that shall be exercised by the President.

“The President is not the repository of executive power, people’s own power,” he said. “The President is only a conduit. Of course, we have understood it in a different way because his duties are huge. From President J.R. Jayewardene onwards, Presidents also have behaved in a monopolistic manner. Presidents, other politicians, especially lawyers and the judiciary, and the media, may interpret it differently.”

According to Chapter VII of the Constitution, the President is the “Head of the Executive”. This means there are other arms of the Executive. Chapter VIII is also titled; “The Executive” and explains one such arm. In it, Article 42 speaks of the Cabinet of Ministers which is “collectively responsible and answerable to the Parliament.”

It means that the Executive power of the People, as in Article 4(b), is shared in practice, Mr. Fernando maintains. Chapter IX, too, is titled; “The Executive” and deals with; “The Public Service”.

“Therefore, I believe the President, the Cabinet of Ministers, and the Public Service all fall under the Executive to specific levels,” he said. “Moreover, the sovereignty of the People rests on a tripod, consisting of the President, the Legislature and the Judiciary” Of course, with the 20th Amendment the status will change.”

In fairness to Mr Sirisena, he did choose to give up certain powers that “anyone would normally like to grab and keep to their hearts”. These included those powers relating to Presidential immunity. The prerogative over appointment of Supreme or Appeal Court Judges was handed over to the Constitutional Council (CC). He could only recommend names. The CC could turn them down.

“I know of two occasions where names he proposed to be appointed to the Supreme Court were rejected,” Mr Fernando recalled. “I think the CC refused to ratify these names for good reasons. Another name he proposed to the Appeal Court was also turned down.”

“The 19th Amendment was a good example of his willingness to give up those Presidential powers,” Mr. Fernando said. “Having done so, however, I wonder how he could now go and vote for something like the 20th Amendment that seeks to restore excessive powers to the President. But that is a matter for him.”

Despite the bad blood between the former President and the former Prime Minister, Mr Fernando said the only time he saw Mr Sirisena being nasty to Mr Wickremesinghe in public was at a meeting held after the Cabinet was sworn at the end of the 2018 Constitutional crisis and Mr Wickremesinghe was made PM again.

“I was not the President’s Secretary at the time but High Commissioner to New Delhi,” he said. “I saw from a video circulated online how the President spoke at the meeting, which was even attended by the PM’s wife, Maithree Wickremesinghe. He was very rough with Mr Wickremesinghe then. I would say that was the culmination of the souring of their relationship.”

Mr Fernando’s personal feeling was that Mr Sirisena’s public dressing-down of his Premier “should not have happened like that”. Presidents are also human being and lose their tempers, he accepted. He didn’t blame him for it.

“But, in most cases, these outbursts have been in private, behind closed doors,” he remarked.

Mr Fernando says Yahapalanaya began promisingly. But the infamous Central Bank bond scam led to a major conflict between the President and PM. President Sirisena appointed a Commission headed by former Supreme Court Justice K.T. Chitrasiri to investigate, although the Central Bank was under Prime Minister Wickremesinghe. This would have frustrated Mr Wickremesinghe. “But” he said, “President Sirisena was right to appoint a Commission”.

Mr. Fernando says he sometimes felt sorry that President Sirisena got a bad name due to policy conflicts initiated by Prime Minister Wickremesinghe. Take the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed between India and Sri Lanka in April, 2017. The relevant Cabinet paper was submitted by the PM. Mr Fernando, as President’s Secretary, helped draft President Sirisena’s observations on it. As the MoU involved so many ministries, it was essentially to obtain the concurrence of relevant Ministers before agreeing to it and to inform Cabinet of their views.

This did not mean the President was against the MoU, Mr Fernando insisted. He was for it. But he wanted the observations of the relevant Ministers to be recorded. Since Mr Wickremesinghe was due to leave for India soon, the Cabinet did approve the proposal. However, Ministers Arjuna Ranatunga and Chandima Weerakkody later submitted their observations on the proposed MoU.

Finally, the MoU that was signed had clauses that contradicted the observations made by the two Ministers, Mr Fernando said: “That was a big policy issue. It shouldn’t have happened that way.”

When he later analysed the MoU, Mr Fernando found that, while it was supposed to have covered subjects like technology, education and agriculture, what was signed contained a substantial section on Trincomalee oil tanks. The intentions, therefore, were questionable.

There was a similar issue with regard to the State Land (Special Provisions) Bill. Mr Fernando was Eastern Province Governor at the time. “The President was not agreeable to some of the proposals made in the bill and he wrote a letter to the PM. I still remember we drafted the letter for him. He made only one or two changes before sending it.

“And then he wanted us to go and speak to the PM. We met the PM and we told him what the President wanted. He said he will make the amendments he requested but I don’t think many of the amendments he proposed were made.”

There are allegations certain forces outside the Government influenced the President against the Premier. There were indeed people who helped the previous Government in an unofficial capacity, including lawyers, Mr Fernando said. But he could not say whether some of them turned the President against the PM.

He denied that Cabinet papers were submitted under the name of President Sirisena without his knowledge. But Mr Fernando admitted that President Sirisena wrote to the Chief Justice seeking a clarification on whether his term lasted for five or for six years, without his knowledge.

“With all due respect to the President (Sirisena), I must say it shouldn’t have happened,” he said. I take my hat off to Presidents Chandrika Kumaratunga and Mahinda Rajapaksa. When they sent letters to the Chief Justice, they made sure that copies came to the Constitutional Affairs Section of the Presidential Secretariat. All those letters are on file.”

“This particular letter was never sent to me or to my branch,” he elaborated. “I checked up on this after I learnt the letter had been sent, to see if it had arrived at the branch without my knowledge. But it was not there. It is not on file. I don’t think it is on file even today, unless someone got hold of a copy after I left and put it there.”

Meanwhile, Mr Fernando faced issues from “fake hangers-on” who carried tales against him to the President and sought his removal. None of them had the guts to confront his directly.

When he took up the position of Secretary, in July 2017, he was already 75 years of age. He did not want to take it up because he felt it should go to a younger person.

“The other reason I was reluctant was that I knew these conflicts were going on between the President and the PM,” he said. But Mr Fernando told Mr Sirisena he will take the job for a short period since he had to consider his own health and the pressures of the position. That turned into one year.

“When I also found that there were people around him making complaints against me, I thought, ‘Why should I be there?’ I didn’t want to hang onto a job which I never wanted,” he said.

“Politics is a dirty game,” he concluded. “These things happened from President Jayewardene’s time and will continue to happen in the future. I look at it dispassionately, as an old man, because you can’t correct them. No one can correct a President, whether you are his Secretary, Prime Minister or a Minister. They think they have the power and they behave like that.”

When President and PM clashed, Secretaries took President’s side; afraid to take orders from PM

- Differences between the President and PM — Personal problems at the beginning

- “Someone” teamed up with the President then to introduce political differences

- “They didn’t care about the economy”

By Damith Wickremasekara

Personal problems between President Maithripala Sirisena and his Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe started as early as the latter part of 2015 –the very year they formed the Government together — and was rooted in class issues as well as a language barrier, said Saman Ekanayake, who was the Premier’s Secretary at the time.

“What I believe was it was a personal problem at the beginning,” said Mr. Ekanayake. “There were two different classes represented. The former President was from Polonnaruwa and the former Prime Minister was from Colombo 7, educated at Royal College. There was a mismatch.”

The first issue Mr Ekananayake noticed while attending to duties was the language problem. Then, someone who did not like Mr Wickremesinghe teamed up with Mr Sirisena and made matters worse by introducing political differences.

“What appeared to be a personal issue was intensified by these groups,” he said, refusing to elaborate further.

There were other shortcomings. The UNP backed Mr Sirisena as the common candidate and propelled him to power but they did not involve him (in running the government). Mr Ekanayake says he pointed this out to the PM and other Ministers.

“They left him out,” he reflected. “This helped other forces to (negatively) influence the President.”

But before the Presidential election of 2015, things had been vastly different. Former president Chandrika Kumaratunga once told Mr Ekanayake that one of Mr Sirisena’s requests was to be allowed to address Mr Wickremesinghe as “Sir”. Upon his election, President Sirisena publicly said he would be doing just that. But it is clear this relationship was not built upon such early niceties and respect, and the language barrier widened the gap between the two leaders.

Mr Ekanayake joined the public service in 1985. Four years later, when the late President Ranasinghe Premadasa gave Ranil Wickremesinghe the Industries portfolio, the young minister invited Mr Ekanayake to serve in the ministry. He declined. But when Mr Wickremesinghe became Prime Minister in 1993 upon President Premadasa’s death and the elevation of then Prime Minister D.B. Wijetunege to the Presidency, he joined the PMO (Prime Minister’s Office) as Assistant Secretary.

Subsequently, when Mrs Kumaratunga was elected PM in 1994, Mr Ekanayake was shifted to the Samurdhi Ministry. He would meet Mr Wickremesinghe, who was Opposition Leader.

In 2008, Mr Ekanayake was attached to the Sri Lankan High Commission in London when Mr Wickremesinghe visited. As Opposition Leader, he enjoyed the privileges of a Cabinet Minister. So he was picked up from the airport and provided with accommodation. Mr Ekanayake was assigned the task of arranging the visiting Opposition Leader’s itinerary and handled those duties whenever he visited thereafter.

Having maintained contact with him, Mr Ekanayake received a phone call from Mr Wickremesinghe on January 9, 2015, after he was sworn is a Prime Minister of the Yahapalana National Unity Government. “You will have to come as my Secretary,” he said. And this time, he said he agreed without any hesitation, accepted the invitation and assumed duties the following day.

Mr Ekanayake had no difficulty working with the PM, whom he said was “a thorough gentleman who never gets angry and is very good to and respects officials”. While some targets were challenging, he managed it all. When officials, on occasion, didn’t cooperate, he spoke to Ministers and got the job done.

The problems between Mr Sirisena and Mr Wickremesinghe, in Mr Ekanayake’s belief, did not stem from the bond scam. The Government started off with the 100-day programme and wanted to hold elections at the end of it. That was delayed. There were political issues. The President didn’t dissolve Parliament immediately. He wanted to strengthen himself and took time.

Meanwhile, the bond scam broke and was used by the Opposition during the election campaign to attack the government. It had an impact on the UNP. Differences continued although the PM didn’t show it. He would call the President, go and meet him and continue with work. The working relationship was not affected. But many wanted to create a rift between the two.

“Although I wasn’t involved in politics, I believe, as a citizen, that the President announcing he would contest for a second term also had an impact on the relationship between the two sides,” Mr Ekanayake said. And the differences (between the UNP and the SLFP) sharpened towards the latter part of 2015.

Mr Wickremesinghe never referred to the President by his name. It was always as President or HE (His Excellency), Mr Ekanayake maintains. He didn’t say a word that eroded the respect of the President, personally or his office. When someone told him what the President has said about him in a negative sense, the PM would shrug it off or smile slightly–not worry, sulk or lose his temper.

But the split was not too visible on the outside and there were no major hiccups (in the administration of government). Work continued till October 26, 2018, when all-of-a-sudden Mahinda Rajapaksa was appointed PM.

Just the day before, on October 25, Mr. Austin Fernando, Secretary to the President had hosted Mr Ekanayake and other officials to lunch. There was no indication of what would transpire the next day: “Nobody knew what was impending.”

The following day, Mr Ekanayake was going out when the PM’s chief of staff Sagala Ratnayake called him. He had heard that Mr Rajapaksa had been sworn-in as the Prime Minister and wanted him to check it. He confirmed it with a friend and notified Mr Ratnayake. This is how Mr Wickremesinghe, who was in Galle at the time, came to know (of his dismissal from his job).

“Not even police officers knew this,” Mr Ekanayake related. “When we gathered at Temple Trees that night, Inspector General of Police Pujith Jayasundara was waiting in the conference room. Even he didn’t know. He suddenly disappeared and had gone to see Mr Rajapaksa. Not even intelligence officers knew.”

A personal relations issue had turned into a high stakes political issue. The United National Party (UNP) is known to be market-oriented. The Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) is more Leftist oriented. With no agreement on policies, there is bound to be conflict during governance. Other persons aggravated the differences. And when the President said he would contest for a second term, it meant a challenge to those in the same Government.

“Until Sajith (Premadasa) became the (Presidential) candidate at the last moment, Ranil Wickremesinghe had not given up the idea of contesting,” Mr Ekanayake said. But he didn’t push for it, he says, and did not make it an issue or go on to destroy his rival (Mr Sirisena).

This turned out to be a disadvantage to him. Had he established himself as the contestant at the next presidential election, the incumbent President Sirisena couldn’t have said he would contest. But Mr Wickremesinghe thought the issue would get resolved with time. Eventually, however, the pressure built up against him.

When a section of the media criticised the PM, some Ministers proposed that the Government stops advertising with them, particularly by institutions under his purview. He did not agree. As the son of media stalwart Esmond Wickremesinghe, he held a different opinion and did not wish to interfere with media freedom.

Some pledges in the manifesto could not be implemented. They include the proposed Special Land Provisions Act under which land was to be given to the landless. It was opposed for, among others, political reasons. “Because of his ambition of becoming President, things that were favourable to Mr Wickremesinghe may have been left out,” Mr Ekanayake opined.

When a Cabinet Committee on Economic Management (CCEM) was set up, the President was influenced into thinking it was taking all the important decisions. It was eventually disbanded, and the President started the National Economic Council (NEC). That body thereafter took all decisions. But this, too, was disbanded after a while with Mr Sirisena himself calling what he had created a “white elephant”.

Saman Ekanayake – ex-Secretary to former PM Wickremesinghe

With the CCEM gone, important decisions regarding the economy couldn’t be taken, Mr Ekanayake said. “It was about power,” he asserted. “They did not care about the economy.”

With the situation deteriorating and bipartisanship crumbling, Ministers Malik Samarawickrema and Mangala Samaraweera tried to resolve disputes between the UNP and the SLFP leadership. The PM would also, sometimes, send delegations to meet the President. Once, President Sirisena wanted to prorogue Parliament but the two Ministers negotiated with him and kept the Yahapalana Government going.

There were “a couple” of officials who contributed to the rift by aggravating the differences. Others were scared to work under the existing system, particularly reading that the President would object to anything they did.

“Since they are appointed by the President, the tendency was to listen to the President,” Mr Ekanayake recalled. “Some Secretaries did not respond to our telephone calls. Their loyalty was towards the President as they were appointed by him. But 95 percent of them cooperated. As for some, we spoke through Ministers to get the work done.”

Among the positives of the last Government was the passing of the 19th Amendment under which independent commissions were appointed. The Right to Information Act was another. The Moragahakanda project, commencement of the Port City project and several other development initiatives, too, were achievements, along with the start of highway projects.

The mistake was no publicity was given to the work done by that Government. It was a weakness throughout the period of the Government. So many important meetings were held and decisions taken. They were not given sufficient publicity. People did not see the work done. That made it easier for the Opposition. The Government had no media strategy. The media was not handled well.

“One thing to remember is that, during the four-and-a-half years, despite the political differences, the administrative system continued,” Mr Ekanayake pointed out. “There was no breakdown until the next President was elected in November last year.”

Sometimes, some Secretaries went on foreign trips meant for junior officers. That affected administration work. Tender meetings were delayed due their frequent foreign visits. Some tenders were delayed for over a year. These should be managed by politicians. The free atmosphere was misused by some officials as well, Mr Ekanayake recalled.

Mr. Austin Fernando, who served as President Sirisena’s Secretary, worked with a good knowledge, he said.

“We (Mr. Fernando and himself) worked during periods when there were a lot of (political) confrontations,” he continued. “We had good communication. He sometimes got approval from the President and came to meet the Prime Minister. Particularly on the Land Provisions Bill, he came personally and met the Prime Minister. The President’s ideas, too, were incorporated. But we eventually could not complete it.”

Once, the PM sent a letter to the President recommending the appointment of MP Ranjith Madduma Bandara as Law and Order Minister. But when he met the President, he had said there was no such letter.

“Mr Madduma Bandara came back to us saying he had been cheated as no letter had gone out,” Mr Ekanayake said. “But we had to show the copy to him and convince him.”

Today, Mr. Madduma Bandara is the General Secretary of the party that broke-away from the UNP rejecting the leadership of Mr. Wickremesinghe.

Easter Sunday attack probe: Sirisena, Ranil statements expose hostile vibes

Former President Maithripala Sirisena and former Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe testified this week before the Commission of Inquiry probing the 2018 Easter Sunday terror attacks. Their statements further exposed how conflicts that arose between the two leaders of the Yahapalana Government eventually led to a complete breakdown in communication. This breakdown also affected various branches of the Government, including defence and intelligence agencies, with disastrous consequences.

The statements also showed how differences between the two continued to persist even in the immediate aftermath of the terror attacks. Following are highlights from the testimony given by Mr Sirisena and Mr Wickremesinghe:

Former President Maithripala Sirisena

Former President Maithripala Sirisena

= There is no rule that the Premier has to take part in the National Security Council (NSC) meetings. Accordingly, I decided not to include Prime Minister Wickremesinghe for these meetings. Even on the occasions he did attend NSC meetings, he never commented on anything and left after a short while.

= A bipartisan Government was in power from 2015, but conflicts arose due to power being shared under the 19th Amendment. There were many reasons for this. Back then, things were done according to the needs of NGOs. I opposed this interference by NGOs.

= Though this was supposed to be a bipartisan Government, some did not heed my instructions. Premier Wickremesinghe had told Government ministers not to act on any instructions issued by me. Once he was reappointed as the PM after the verdict of the Supreme Court, ministers did not do anything I asked. That was what really happened. The National Economic Council (NEC) operated under me. PM Wickremesinghe instructed both the Finance Ministry and the Central Bank not to carry out any instructions issued by the NEC. It was this corrupt political system that created all these issues.

= Look at what happened with the Central Bank Treasury Bond scandal. I got myself into this mess by agreeing to an unsuitable marriage with a political demon. This led to a rise in extremism.

= Conflicts arose when appointing Arjuna Mahendran as the Central Bank Governor. Feelings were hurt within the very first week of the formation of the new Government. He (PM) grew angry with me when I appointed a Commission to probe the treasury bond scandal. Conflicts also arose due to the agreement on handing over the Hambantota Port to China and regarding the Free Trade Agreement with Singapore.

= Ranil Wickremesinghe did not like the subject of Muslim extremism being brought up at NSC meetings.

= I don’t remember whether Ranil Wickremesinghe attended NSC meetings after being reappointed PM following the Supreme Court ruling.

Former Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe

Former Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe

= While there were differences of opinion between the President and the Prime Minister, there weren’t many major problems within the Government.

= I did not take part in NSC meetings from 2018 up until the Easter Sunday attacks as I was not invited to these meetings during this period.

= If an incident occurs while the President has gone abroad without appointing an Acting Defence Minister, the next in line should take over and cover those duties. I was Leader of the House at the time President Premadasa was assassinated on May 1, 1993. I took over the Defence Ministry and did what was needed to be done. President Kumaratunga was not in the country at the time of the tsunami. But Premier Mahinda Rajapaksa took necessary actions. Someone has to be there to intervene during an emergency. On this occasion, I acted. I took necessary action after summoning State Minister Ruwan Wijewardene, Harsha De Silva, Kabir Hashim, the Attorney General and the Solicitor General.

= The President did not speak to me after the multiple bomb explosions. I was the one who called him. I spoke to the IGP and ensured that a curfew was declared. I learned later that the President had issued instructions to the armed forces commanders not to go to the meeting summoned by me, but they turned up anyway.

= The President had also instructed Defence Secretary Hemasiri Fernando and the Army Commander not to attend the meeting convened by me. Yet we still took necessary action and even ensured that security was provided along the route the President was taking when he arrived back in the country. I saw it as my duty to ensure the President’s security.

When President and PM clashed, Secretaries took President’s side; afraid to take orders from PM

Differences between the President and PM — Personal problems at the beginning“Someone” teamed up with the President then to introduce political differences“They didn’t care aboutthe economy”By Damith WickremasekaraPersonal problems between President Maithripala Sirisena and his Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe started as early as the latter part of 2015 –the very year they formed the Government together — and was rooted in class issues as well as a language barrier, said Saman Ekanayake, who was the Premier’s Secretary at the time. “What I believe was it was a personal problem at the beginning,” said Mr. Ekanayake. “There were two different classes represented. The former President was from Polonnaruwa and the former Prime Minister was from Colombo 7, educated at Royal College. There was a mismatch.”The first issue Mr Ekananayake noticed while attending to duties was the language problem. Then, someone who did not like Mr Wickremesinghe teamed up with Mr Sirisena and made matters worse by introducing political differences.

“What appeared to be a personal issue was intensified by these groups,” he said, refusing to elaborate further. There were other shortcomings. The UNP backed Mr Sirisena as the common candidate and propelled him to power but they did not involve him (in running the government). Mr Ekanayake says he pointed this out to the PM and other Ministers. “They left him out,” he reflected. “This helped other forces to (negatively) influence the President.” But before the Presidential election of 2015, things had been vastly different. Former president Chandrika Kumaratunga once told Mr Ekanayake that one of Mr Sirisena’s requests was to be allowed to address Mr Wickremesinghe as “Sir”. Upon his election, President Sirisena publicly said he would be doing just that. But it is clear this relationship was not built upon such early niceties and respect, and the language barrier widened the gap between the two leaders. Mr Ekanayake joined the public service in 1985. Four years later, when the late President Ranasinghe Premadasa gave Ranil Wickremesinghe the Industries portfolio, the young minister invited Mr Ekanayake to serve in the ministry. He declined.

But when Mr Wickremesinghe became Prime Minister in 1993 upon President Premadasa’s death and the elevation of then Prime Minister D.B. Wijetunege to the Presidency, he joined the PMO (Prime Minister’s Office) as Assistant Secretary. Subsequently, when Mrs Kumaratunga was elected PM in 1994, Mr Ekanayake was shifted to the Samurdhi Ministry. He would meet Mr Wickremesinghe, who was Opposition Leader. In 2008, Mr Ekanayake was attached to the Sri Lankan High Commission in London when Mr Wickremesinghe visited. As Opposition Leader, he enjoyed the privileges of a Cabinet Minister. So he was picked up from the airport and provided with accommodation. Mr Ekanayake was assigned the task of arranging the visiting Opposition Leader’s itinerary and handled those duties whenever he visited thereafter. Having maintained contact with him, Mr Ekanayake received a phone call from Mr Wickremesinghe on January 9, 2015, after he was sworn is a Prime Minister of the Yahapalana National Unity Government.

“You will have to come as my Secretary,” he said. And this time, he said he agreed without any hesitation, accepted the invitation and assumed duties the following day. Mr Ekanayake had no difficulty working with the PM, whom he said was “a thorough gentleman who never gets angry and is very good to and respects officials”. While some targets were challenging, he managed it all. When officials, on occasion, didn’t cooperate, he spoke to Ministers and got the job done. The problems between Mr Sirisena and Mr Wickremesinghe, in Mr Ekanayake’s belief, did not stem from the bond scam. The Government started off with the 100-day programme and wanted to hold elections at the end of it. That was delayed. There were political issues. The President didn’t dissolve Parliament immediately. He wanted to strengthen himself and took time. Meanwhile, the bond scam broke and was used by the Opposition during the election campaign to attack the government. It had an impact on the UNP. Differences continued although the PM didn’t show it. He would call the President, go and meet him and continue with work. The working relationship was not affected. But many wanted to create a rift between the two.

“Although I wasn’t involved in politics, I believe, as a citizen, that the President announcing he would contest for a second term also had an impact on the relationship between the two sides,” Mr Ekanayake said. And the differences (between the UNP and the SLFP) sharpened towards the latter part of 2015. Mr Wickremesinghe never referred to the President by his name. It was always as President or HE (His Excellency), Mr Ekanayake maintains. He didn’t say a word that eroded the respect of the President, personally or his office. When someone told him what the President has said about him in a negative sense, the PM would shrug it off or smile slightly–not worry, sulk or lose his temper. But the split was not too visible on the outside and there were no major hiccups (in the administration of government). Work continued till October 26, 2018, when all-of-a-sudden Mahinda Rajapaksa was appointed PM.

Just the day before, on October 25, Mr. Austin Fernando, Secretary to the President had hosted Mr Ekanayake and other officials to lunch. There was no indication of what would transpire the next day: “Nobody knew what was impending.”The following day, Mr Ekanayake was going out when the PM’s chief of staff Sagala Ratnayake called him. He had heard that Mr Rajapaksa had been sworn-in as the Prime Minister and wanted him to check it. He confirmed it with a friend and notified Mr Ratnayake. This is how Mr Wickremesinghe, who was in Galle at the time, came to know (of his dismissal from his job). “Not even police officers knew this,” Mr Ekanayake related. “When we gathered at Temple Trees that night, Inspector General of Police Pujith Jayasundara was waiting in the conference room. Even he didn’t know. He suddenly disappeared and had gone to see Mr Rajapaksa. Not even intelligence officers knew.”A personal relations issue had turned into a high stakes political issue. The United National Party (UNP) is known to be market-oriented. The Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) is more Leftist oriented. With no agreement on policies, there is bound to be conflict during governance. Other persons aggravated the differences.

And when the President said he would contest for a second term, it meant a challenge to those in the same Government. “Until Sajith (Premadasa) became the (Presidential) candidate at the last moment, Ranil Wickremesinghe had not given up the idea of contesting,” Mr Ekanayake said. But he didn’t push for it, he says, and did not make it an issue or go on to destroy his rival (Mr Sirisena). This turned out to be a disadvantage to him. Had he established himself as the contestant at the next presidential election, the incumbent President Sirisena couldn’t have said he would contest. But Mr Wickremesinghe thought the issue would get resolved with time. Eventually, however, the pressure built up against him. When a section of the media criticised the PM, some Ministers proposed that the Government stops advertising with them, particularly by institutions under his purview. He did not agree. As the son of media stalwart Esmond Wickremesinghe, he held a different opinion and did not wish to interfere with media freedom. Some pledges in the manifesto could not be implemented. They include the proposed Special Land Provisions Act under which land was to be given to the landless. It was opposed for, among others, political reasons. “Because of his ambition of becoming President, things that were favourable to Mr Wickremesinghe may have been left out,” Mr Ekanayake opined. When a Cabinet Committee on Economic Management (CCEM) was set up, the President was influenced into thinking it was taking all the important decisions. It was eventually disbanded, and the President started the National Economic Council (NEC). That body thereafter took all decisions. But this, too, was disbanded after a while with Mr Sirisena himself calling what he had created a “white elephant”. With the CCEM gone, important decisions regarding the economy couldn’t be taken, Mr Ekanayake said. “It was about power,” he asserted. “They did not care about the economy.”With the situation deteriorating and bipartisanship crumbling, Ministers Malik Samarawickrema and Mangala Samaraweera tried to resolve disputes between the UNP and the SLFP leadership. The PM would also, sometimes, send delegations to meet the President. Once, President Sirisena wanted to prorogue Parliament but the two Ministers negotiated with him and kept the Yahapalana Government going. There were “a couple” of officials who contributed to the rift by aggravating the differences. Others were scared to work under the existing system, particularly reading that the President would object to anything they did. “Since they are appointed by the President, the tendency was to listen to the President,” Mr Ekanayake recalled. “Some Secretaries did not respond to our telephone calls. Their loyalty was towards the President as they were appointed by him. But 95 percent of them cooperated. As for some, we spoke through Ministers to get the work done.” Among the positives of the last Government was the passing of the 19th Amendment under which independent commissions were appointed. The Right to Information Act was another. The Moragahakanda project, commencement of the Port City project and several other development initiatives, too, were achievements, along with the start of highway projects. Please turn to page 14

Count. on page 13The mistake was no publicity was given to the work done by that Government. It was a weakness throughout the period of the Government. So many important meetings were held and decisions taken. They were not given sufficient publicity. People did not see the work done. That made it easier for the Opposition. The Government had no media strategy.

The media was not handled well.“One thing to remember is that, during the four-and-a-half years, despite the political differences, the administrative system continued,” Mr Ekanayake pointed out. “There was no breakdown until the next President was elected in November last year.”Sometimes, some Secretaries went on foreign trips meant for junior officers. That affected administration work. Tender meetings were delayed due their frequent foreign visits. Some tenders were delayed for over a year. These should be managed by politicians. The free atmosphere was misused by some officials as well, Mr Ekanayake recalled. Mr. Austin Fernando, who served as President Sirisena’s Secretary, worked with a good knowledge, he said. “We (Mr. Fernando and himself) worked during periods when there were a lot of (political) confrontations,” he continued. “We had good communication. He sometimes got approval from the President and came to meet the Prime Minister. Particularly on the Land Provisions Bill, he came personally and met the Prime Minister. The President’s ideas, too, were incorporated. But we eventually could not complete it.” Once, the PM sent a letter to the President recommending the appointment of MP Ranjith Madduma Bandara as Law and Order Minister. But when he met the President, he had said there was no such letter. “Mr Madduma Bandara came back to us saying he had been cheated as no letter had gone out,” Mr Ekanayake said. “But we had to show the copy to him and convince him.” Today, Mr. Madduma Bandara is the General Secretary of the party that broke-away from the UNP rejecting the leadership of Mr. Wickremesinghe.