A forest is much more than just a collection of trees

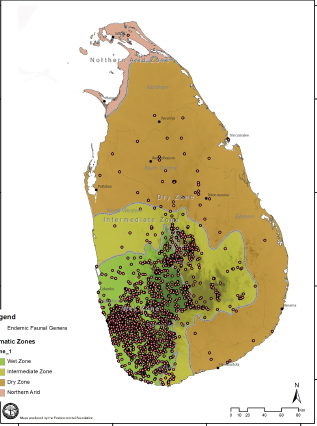

This map shows the distribution of endemic animal species of Sri Lanka. The rainforests of the southwestern quarter and the central mountains contain most of the endemic biodiversity, including the endemic species. (Biodiversity profile of Sri Lanka, Ministry of Environment 2020)

Trees don’t make a forest. That’s a fact.

Tree planting has become a national obsession. Indeed, even a global obsession. The year before COVID saw a competitive clamour to plant the most trees per day- with countries like India, China and Ethiopia vying for top spots on the global tree planting rankings.

However, a collection of trees does not make a forest or an eco-system that supports myriad of plant and animal life. A collection of trees will give us shade, provide food for people and animals, arrest the erosive force of heavy rain and soak up carbon dioxide from the air. But a forest is much, much more. Many of us, however well intentioned, do not see the forest for the trees. Therein lies the fundamental issue that we are faced with today. Are forests wasted space? Expendable and easily replaceable by planting trees?

During the time when planting new trees reached giddy heights, old-growth and secondary forests were being converted to other uses at an alarming rate. A new global report on the world’s biodiversity is a sad reminder of this predicament. In the next 10 years, we would have engineered the extinction of many species driven by our own wasteful greed for more. While 2020 will be remembered for the COVID pandemic that has shrouded the planet, it is also a record year for forest fires and habitat destruction- from Australia to the Pantanal to California- global forest destruction has reached a peak.

Replaceable, renewable,

undervalued and misunderstood

The economic crisis perpetuated by the COVID-19 pandemic has forced many countries to compromise on environmental safeguards and conservation objectives, earlier accepted and endorsed to support short term economic revival or wealth creation strategies- knowing well that the macroeconomics that led to this global environmental crisis cannot save us from it. The United States is the best or worst – depending on how you look at it- example of aggressive regulatory rollbacks to push investments in industry and mining during the pandemic. Among many other moves, the Trump administration has effectively suspended enforcement of air and water pollution regulations, undermined the government’s role to block unclean energy projects, and suspended legal requirements for environmental review and public input on new mines, pipelines, highways, and other projects.

Brazil’s state-sponsored destruction of the Amazon rainforest continued unabated and possibly under-monitored even as the pandemic raged through its population. India, another country hard hit by COVID is looking at auctioning mining rights to extract coal in its biodiversity-rich central forests. Other countries, hit hard by the pandemic and its impact on trade, tourism and manufacturing will look to trading natural assets, favouring more mining and extractive uses that can bring quick income to cash-strapped governments.

In Sri Lanka too, the argument to release more land (earlier protected as ‘other state forests’) for cultivation stems from the need to trim the import bill and steady the balance of payments, by growing as much locally the required food for people and farmed animals. Forests, in this case, are considered as unproductive, wasteful or easily renewable (we can grow trees elsewhere).

There is a misconception that land is the bottleneck or the limiting factor for agricultural production. Sri Lanka’s agriculture is among the worst performing in the world, in terms of land and water requirement per ton of output (whether rice, other cereals or vegetables). Food and crop wastage is huge. All this despite billions of rupees in investment into agricultural innovation, new crops, extension services and most of all, free fertilizer as a government policy for the past 20-odd years. By releasing more forests for unproductive agriculture, we are most likely to create a new generation of subsistence farmers with low productivity, limited income, more exposed to drought and intense rainfall (which are becoming more frequent with time) and putting more people in the frontlines of the human-wildlife conflict.

Seeing the trees but

not the forest

It is hard to reiterate this more. You cannot replace a forest- not for a long, long time. Some functionality of a forest could be replaced by restoration efforts and some agriculture types that mix in trees and shrubs to mimic the many different layers of a natural forest. But an old growth forest, which has got there through many generations of succession, is not something we can replace by planting trees. Plus, restoration of any forest is expensive, time consuming and open to many risks (fire, climate hazards, animal and pest attack etc). Once destroyed, expensive reforestation efforts are rarely repeated.

In Sri Lanka, the forests in its rain-rich Wet Zone contain plants and animals that are not found anywhere else in the world. The recent Biodiversity Profile of Sri Lanka show that its extraordinary diversity is clinging to slivers of remaining forests in the Wet Zone – which have been expansively developed and cultivated for tea, rubber, coconut, townships and industrial parks. Yet these remaining patches and fragments of rainforests can harbour yet undiscovered species and contain many more species in a few acres than the vast Dry Zone combined.

Rainforests, once opened up, cannot sustain agriculture without heavy chemical input. This is because the recycling of essential nutrients within the forest eco-system is so efficient in hot, wet climates that the soils are not deep and fertile as in colder countries. Clearing of rainforests for cultivation has never yielded longlasting productivity and will instead create more farmers dependent on free and cheap fertilizers.

All our rivers are born in forests. Rivers heavily tapped for human use, drinking, industry, agriculture and power generation are dependent on rain-soaking vegetation that forests provide. In the sub-soils below dense canopies that do not let in sunlight, rainfall is transformed into springs and rivulets that collectively form the massive rivers downstream. For forests to keep yielding clean, fresh water even as rainfall becomes more unpredictable, intense and unmanageable, they have to be intact- not just in extent but also in structure. An intact forest is not a collection of trees like a rubber plantation or a tree-filled home garden, but a functioning system whose many parts – both plant and animal – come together to create a super organism that provides clean air, fresh water, cools down rising temperatures and provides food and medicine to many people.

Forests are the source of life. Technology has not yet innovated ways to replace the functionality of a forest eco-system. A collection of fast-growing trees cannot replace a mature forest. All these are factors to keep in mind, as we go about converting these forests to ‘more productive’ uses. It takes a day to burn down a forest but many generations to build one.

The writer is a technical advisor to natural

resources management projects/programmes