A teacher from his teens walks along the corridors of time

Two leading Buddhist schools with a shared history celebrate their respective birthdays today

Ananda was just 28 years of age when I had the good fortune of throwing myself, heart and soul, into its service as a member of the tutorial staff under Principal Fritz Kunz in May, 1914 – the historic year of the outbreak of World War I. Mr. Kunz had just succeeded M.U. Moore, who had, over just three years, not only continued the yeoman service of his predecessor, but also produced appreciable examination results quite consistent with Ananda’s formative years.

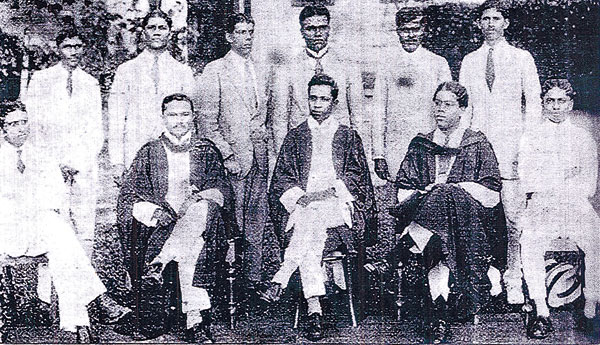

Ananda College teaching staff--1919: Seated L to R: S.A. Wijayatilake, J.N. Jinendradasa, P.De. S. Kularatne (Principal), G.P. Malalasekera and C.V. Ranawake Standing L to R: T.B. Jayah, C.E.P. Kumarasinghe, V.I. Perera, V.T.S. Sivagurunathan, C. Suntharalingam, and W.E. Fernando

At the commencement of the second term, i.e. May 1914, I saw the Principal with my letter of appointment for instructions as regards my duties. After examining my certificates and other documents, he assigned me to the Middle School. I had only provisional certificates as a qualification which had to be endorsed by the various Inspectors at the annual inspection of the school. Increments to salaries were determined by the management in accordance with these endorsements. Those were the days of the State Grant-in-aid to teaching institutions, which largely depended on the Annual Inspection Report. It was a rather harrowing experience for a teacher to go through the ordeal of teaching a class in the presence of a lynx-eyed Inspector.

On one occasion, C.A. Wicks, M.A. of an English University, as Inspector of Maths, sat in a corner of the classroom to watch me giving a Geometry lesson on polygons. To engage me in conversation about the syllabus, he drew a hexagon on the board and joined angular points to form triangles, each standing on a side. A daredevil student surreptitiously manouevred to draw another line so as to make the figure have an additional triangle. The conversation over, Wicks got near the blackboard and put the question to the boy, “How many triangles do you observe in the figure?” Came the reply “Seven.” Repeating the question, he was told,”Seven, Sir.” Posing it the third time, he got a chorus of voices “Seven, Sir”. “No,” he bawled. “Oh, no, Sir!” they bellowed reciprocally. After the inspector had gone, there followed a thunderous babel over the comic scene.

Another time, a Classics Inspector, L.G. Gratiaen, a distinguished Old Royalist, walked into my Latin class. Being an inexperienced teacher yet in my teens, I had been observed to be thundering in stentorian tones in the course of the lesson. Before he walked out he made a passing remark savouring of the reproachful – “Vox magister detrimentum discipuli”. What he hinted at was that the high-pitched tone of a teacher is a hindrance to the understanding of the pupil. I gave my thanks for his advice.

The original school building was T-shaped with a row of separated classrooms in each of the horizontal and vertical sections, with open sidewalks running on either side of them. The Principal’s room stood at the right end of the horizontal wing. There was no staff room as such. One really felt one was living in an emergency atmosphere.

The front portion of this two-acre block of land was open land whilst at the back of the building there was a square-shaped patch that had been used for a playground. It looked a virtual juvenile cricket pitch but it had nurtured the school’s early cricketers amongst whom was Ananda’s first All-Ceylon player, D.L. Gunasekera, later a well-known lawyer practising in Hulftsdorp.

On the Mackwoods side of the vertical wing of the main building Principal Kunz managed to build the spacious Olcott Hall, the first major addition to the College, after nearly 30 years. Shortly afterwards, the Dias Memorial Laboratory was put up on the highway end of the Hall through the munificence of the philanthropic Jeremias Dias family of Panadura.

It was after the erection of these two buildings that the College was registered for Government Grant as an Elementary School with a Secondary Department running up to the Cambridge Senior, the examination that determined the Govt. Scholarship on its results for the year.

Another of Kunz’s firsts was the establishment of a hostel for outstation students who were beginning to storm the school as it was now functioning as satisfactorily as any of the well-established institutions. The College boarders were housed in a large upstair building called “Starlight”on Jail Road, a few yards away from the present St. Anthony’s Church. This hostel was shortly afterwards shifted to a very spacious single-floor building called Kityakara also bordering the road but on the opposite side – an ancestral mansion of the famous cricketing family -the Goonesekeras.

I wonder even now, over 70 years later, if my appointment as the Sports Master in charge of the team and of other games activities, was another of Kunz’s firsts. After the performances of the school’s early players, especially of its first All-Ceylon cricketer, D.L. Gunasekera, Ananda began to play inter-collegiate matches. If they are still among us, T.K. Burah, H.R. Perera, two distinguished players and others of the day are sure to bear testimony to my information.

In Kunz’s first year of Principalship, the titanic World War I broke out. The next year saw the Sinhala-Muslim riots, the proclamation of Martial Law and its horrible aftermath. The leaders of the country were incarcerated and their lives were at stake. Into the bargain, the land was in utter disorder and distress. Kunz faced all odds with unflagging courage. In short, he endeavoured not merely to maintain the school’s standard of his predecessors, but also elevate it with additional improvements.

His Vice-Principal was one Menon, a graduate from an Indian University and his Headmaster Dandris de Silva, who was acting when he took over. The latter was a typical schoolmaster of Goldsmith’s description. He was wont to wear a full white suit, the coat being full-buttoned. The staff included C.V. Ranawake, A.P. de Zoysa, J.R. Peiris, J.E. Goonesekera, W.G. de Silva, affectionately known as “dadi-bidi”, W. Dharmarama, V.T.S. Sivagurunathan, Sundar Raman, W. Martin Silva and many more. During the entire period (1914-26) I was at Ananda, there prevailed an excellent camaraderie among the teachers.

P de S. Kularatne assumed duties as Principal in January 1918, fresh from London University where his career had been as brilliant as at Richmond in his final schooling years. He had obtained a first class at the B.A, and the BSc and a second at the LL.B. He had also qualified as a Barrister-at-Law. On assuming duties Kularatne instinctively realised the glaring priorities of the school. He also unerringly anticipated a steady influx into the school with visible improvements. He showed no hesitation in launching a building scheme, even though he knew he had to surmount distressing odds.

Some affluent Buddhists realising his determination and high-mindedness of purpose came to his assistance.

His first building was a block of classrooms running alongside the roadway leading to the College. The last spacious room with a separate entrance was set apart as the Teachers’ Room, the staff having been strengthened by then.

Then he set about the task of building a hostel. Considering the exigencies of the time, a building project of that nature stood as a tremendous task. Nevertheless, he started a countrywide collection campaign. I remember going out into the remote interiors with three of my colleagues to meet Old Boys and well-known Buddhist families. It was a perilous tour for we got marooned somewhere in the waters of the great deluge of that year.

Concurrently, with his all-out drive for raising funds proceeded his well-conceived scheme for a rapid development of the school in the intellectual sphere. Along with his offer of free scholarships to bright students chosen on the results of a competitive exam, he manoeuvred to ferret out some excellent academic talent in the teaching sphere. Thus, he managed to have on his staff a galaxy of distinguished teachers of the day, each one of them a conspicuous figure in his line. It was a staff the like of which no other school had: C. Suntharalingam (Maths), G.P. Malalasekera (Languages), T.B. Jayah (Western Classics), William Perera (English), Walter Samarasekera (Western Classics), G. Weeramantry (Maths), Rao (Science), Roland de Zoysa (Science), J.N. Jinendradasa (Science), C.E. Strange (Maths), S. De S. Jayaratne (Classics), G.G. Ponnambalam, G.M. de Silva, and L.H. Mettananda.

Within a year or two, the well-conceived plans paid rich dividends. At the Cambridge Locals the College scored honours and distinctions and perhaps threw into shade many an outstanding school of the day. E.A. Wijesuriya, M.L. Salgado, M.F. de S. Jayaratne, M.W.F. Abeykoon, J.G. Fernando were among those who shone, the first-named coming first in the island. This flow of successes continued thereafter enhancing the fame of the school till Ananda stood shoulder to shoulder with the other great educational institutions of the time.

The unexpected had happened. Parents from all over the country were clamouring to get their children admitted to the school. Kularatne hit upon the idea of opening up a sister institution and successfully pleaded with the Government for land. The land thus obtained, a sizeable block of veritable jungle land in the Campbell Place region was cleared and two rows of cadjan-made classrooms were put up to accommodate about three to four hundred children, most of whom had been released from the College. Kularatne put in charge W.E. Fernando, a remarkably energetic and excellent teacher who eventually retired as Headmaster.

Kularatne also enlisted a band of supporters on whose aid he raised enough funds to erect an imposing two-storeyed structure – the nucleus of Nalanda’s building complex. The school population of these cadjan makeshifts was subsequently transferred to the new building to make up the lower grades. Kularatne released from the main school a tolerable number of bright students to make up the middle and upper grades.

Nalanda Vidyalaya was christened after one of the famous Buddhist Universities of ancient India. In order to make this new school a real sister institution he released six hand-picked teachers Cyril E. Strange, S.A. Wijayatilake, J.N. Jinendradasa, V.I. Perera, D.C. Lawris, and my humble self. G.P. Malalasekera was appointed Principal.

In a couple of years this younger sister eclipsed the elder in academic success. My recollection is that Nalanda scored the best results in the Cambridge Senior and Junior exams in a number of consecutive years. None in creation could have rejoiced more at this phenomenal performance than the courageous and inspired founder.

His enthusiasm and concern were not confined to Ananda and Nalanda. Under his penetrative vision he directed endeavours towards the furtherance and consolidation of Buddhist education in particular, opening up schools for boys and girls in different parts of the country, such as Dharmapala Vidyalaya, Pannipitiya, Sri Sumangala, Panadura and Ananda of Gampaha. His original Ananda Balika Vidyalaya of Temple Road was later transferred to Maligakanda; Sri Sumangala Girls’ School came later.

After accomplishing the arduous task of raising the two big Buddhist institutions to towering heights and establishing a network of feeder schools, he directed his attention to the rehabilitation and restoration of institutions that were far below the accepted standards. He became Principal of Dharmaraja and of Sri Sumangala. Finally he occupied the position of General Manager of Buddhist Schools, which enabled him to watch the progress of Buddhist education in the island.

Patrick de Silva Kularatne was the name he adopted after he completed his academic career. To his school contemporaries, he was the lovable and affable S.K.P. de Silva, a name which adorns the exam results boards of Distinguished Old Boys of his old school, Richmond College, Galle. I knew Kularatne as S.K.P. de Silva in my school years at Richmond where in his later years he was a college prefect. He used to be surrounded by his schoolmates with requests for solutions of mathematical problems and the translation of Latin and Greek passages. He maintained the honour of his school as the home of mathematics, for it is in this sphere that he had shown his extraordinary talents both at College and University.

From the very outset of his assuming duties as Principal of Ananda in January, 1918, till he retired from active service Kularatne had made it clear that his life’s aim and desire was not merely the cause and progress of Buddhist education, but also the improvement of Buddhism as well. Very few know that it was he who started classes for the Buddhist clergy to learn English at a vacant building in Paranawadiya Road in the mornings conducted by teachers from the regular staff. These classes continued later at the Vidyodaya Pirivena. Some of the Buddhist clergy who received this help later published books in English on Pali and Buddhism.

Kularatne was a virtual human dynamo. Thus, he was cut out for the formidable task his destiny had set for him.

The meteoric rise of the Mariakade school and the brilliance of exam results of several consecutive years seemed miraculous as the change had come about within an incredibly short spell of time.

Finally, his selfless service to the national cause in general and to Buddhist education in particular, will, quite apart from being immeasurable and epoch-making, remain evergreen in the grateful hearts of generation after generation to come.

This article written for the centenary of Ananda College in 1986, was sent in by the writer’s son, Meghavarna Kumarasinghe, himself a senior Old Anandian, closely associated with the school for over

50 years as a student, Committee Member of the Old Boys’ Association and Joint Secretary of the Senior Old

Anandians group.