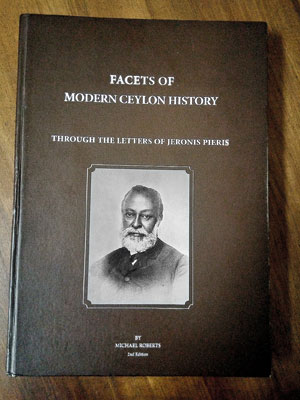

Family sagas and a peek at Victorian Ceylon’s westernised bourgeoisie

Few voices of the early 19th Century bourgeois Ceylonese have survived straight from the horse’s mouth to-date. Who were this new elite? What were those first English-educated generations like? How did Macaulay’s “class of people who can act as intermediaries between us and the millions we govern- English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and intellect” fit in?

A photograph of Charles Henry de Soysa’s wedding

Many answers are woven into this book. It shows how Hannadige Jeronis Pieris and his clansmen from Moratuwa, canny and blessed with the Midas touch, burst out as compradors; how they flourished in baroque neo-walawwas in Colombo to rival English stately homes where, as that old saying goes, they ‘fed British royalty on gold plate’.

It would seem apt that author, historian Michael Roberts, would have chosen personal letters by Jeronis (also uncle and mentor to Sir Charles Henry de Soysa), written from 1853 to 1877, to illumine certain ‘facets’ of modern Ceylon history seeing as this Karava clan was in the thick of it.

But, before we get to that cake, the icing:

This deluxe second edition is elegantly opulent compared to the original 1975 edition. The images in the new coffee table size volume bring alive “those… times when the modernization of the island was being effected by the engines of British rule, involving capitalist framework as well as a bureaucratic administrative dispensation”.

Off vintage family albums come images of the key characters related to the letters- the women in corseted and crinolined gowns; men poised with kadu kasthana- many of them looking ill at ease but also the sometimes impossibly grand world they lived in- colonial mansions like the Regina Walawwa and Alfred House, ample evidence of their philanthropy, and heady images of Victorian Ceylon captured in lithograph and early photos.

The 24 letters themselves come at the end of the book making for plodding reading given that the writer, Jeronis in his adulation for Addison and Macaulay makes sure he sounds ponderously gentlemanly. He exhorts and admonishes (his younger brother Louis and nephew Charles to study); and he often quotes the Bible.

A painting of Jeronis

Letters are also written to George Pride and W. H. Wright (with a note of obsequity), S.C. Perera, Simon Perera and a final Sinhala letter written while in his Mecca describing Scottish lochs and English houses to his mother and sister. These have been published mainly, according to Michael Roberts, to ‘make them more widely available to scholars (and to) provide interested laymen with some insights into developments in mid-nineteenth century Ceylon’.

But in the first part of the book Roberts has the pleasure of himself mining the letters which come from a period for which he has a special penchant. “The letters” he says, “have been variously used (in the book) at times as a point of departure for the investigation of various subjects on which they throw some light, and at other times as a convenient showcase in which to display conclusions fashioned… out of other evidence.”

With his abiding interest in elite formation (explored in People In-between (1989) and Caste Conflict and Elite Formation: The Rise of a Karava Elite in Sri Lanka, 1500-1931 (1982)) Roberts is eminently placed to mine this epistolary cache.

But while that cache of letters is indeed a wonderful thing to chance upon for the historian, these letters remain sketchy- offering no historical sidelights and little cultural or social detail.

In fact more than the Jeronis letters themselves, it is Roberts’s deft interpretations, commentary and the illustrations that conjure up the era.

What the letters do reveal, starkly and brilliantly, are the ethos and psychological makeup of your comprador. Not only does Jeronis assiduously copy the style of an English gentleman, he also talks about the ‘barbarous’ Kandyans and their ‘old nasty customs’ particularly polygamy. It goes down to expounding the Bible to the British and using anglicised names like Hangurangcutte.

For him acquiring English ways meant upward mobility, sophistication, erudition as well as (he seems to believe more or less) spiritual salvation. That fervour to acquire and adore all things British is patent in every line. This, we must remember, was long before our elite wanted a part of the government.

Michael Roberts

While the letters yield little historical information, Dr. Roberts has adroitly extracted all that he can.

The ‘facets’ he explores are: the foundation of social dominance within indigenous society in pre-British times; the processes of elite formation in the 19th century; the process of westernization and the role of indigenous elites as auxiliaries and supporters of the colonial rulers; the events leading to the Kandyan Marriage Ordinance No 13 of 1859; entrepreneurship; the question of the conflict for land between coffee planters and villagers in the Kandyan hill-country; and the question whether the expansion of plantations had disastrous effects on the stock of cattle in the Kandyan districts.

While he dexterously plumbs, Roberts is able, through the family sagas of the Pierises and the de Soysas, to map the origins and evolution of the comprador bourgeois class: their move from primary trading ventures to the farming of arrack and toddy rents, and thence to opening coconut and rubber plantations and acquiring all the airs and graces of the colonial masters.

Former reviewer the late H. A. I. Goonetileke however found the last two facets ‘controversial’. Goonetileke thought that Roberts’s sweeping deduction from the letters- that the buffalo was not an integral part of the Kandyan village economy “before the thirst for coffee and the Crown lands ‘enclosure’ movement” ignored “regional peculiarities”- as in the terraced paddy fields in Hanguranketa (where Jeronis’s observation was made) “neither the buffalo nor the bullock can be put to much use.”

Goonetileke states too that Roberts “will have to produce more trenchant and consistent evidence if he is to sustain his line that traditional land use and village community structures were little affected by the encroachments of coffee, tea, rubber and coconut over a long period of time as well as to dispute the view that, although expropriation under the Waste Lands Ordinance (of 1840) may not have been done en masse, a great deal of village land changed hands in various ways in the climate of uncertainty, and even panic, provoked by official land policy, as well as the prevail¬ing land rush.”

Goonetileke states too that Roberts “will have to produce more trenchant and consistent evidence if he is to sustain his line that traditional land use and village community structures were little affected by the encroachments of coffee, tea, rubber and coconut over a long period of time as well as to dispute the view that, although expropriation under the Waste Lands Ordinance (of 1840) may not have been done en masse, a great deal of village land changed hands in various ways in the climate of uncertainty, and even panic, provoked by official land policy, as well as the prevail¬ing land rush.”

But to make up for all that the book is crisply readable with that lucidity good anthropologists and social historians bring in to their writing.

The rambling genealogies at the end of the Hannadige Pieris and Warusahannadige de Soysa families form, to borrow Ian Goonetileke’s words, a ‘perahera’ of Colombo’s beau-monde, few families not being woven in at some point or the other.

The book, finally, is much more than a tool for researchers, it is a time capsule from Victorian Ceylon which allows you to penetrate that sepia world- an unusual monument to that twilight period where its elusive but utterly heady tenor survives almost in full.

Priced at Rs. 6500, the book is available at all leading bookstores.