News

Road ahead: Statesmanship or 20A authoritarianism?

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa: People expect him to govern with clinical efficiency and single-minded determination to ensure a better nation for all

The story is told of when Sarath Fonseka, the then Army Commander, was hospitalised after sustaining serious life-threatening injuries in a suicide bomb attack at Kollupitiya in Colombo in April 2006. The most frequent visitor at his bedside was the then Defence Secretary, Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

Secretary Rajapaksa would arrive daily and spend a few hours talking to doctors treating Fonseka, inquiring about his prognosis for a complete recovery. At the time, Fonseka was unconscious, on a ventilator and medical opinion was divided on whether he would survive the attack.

In one such discussion, Secretary Rajapaksa told doctors, “I want this man saved”. One senior doctor responded, saying ‘Sir, we are doing our best”. Rajapaksa turned, fixed a steely stare on him and said sternly in Sinhalese, “Doctor ta mama kiyapu eka theruney nehe wageyi, mata mey manussayawa berala oney” (Doctor, I don’t think you understood what I said. I want this man saved”).

Fonseka did survive and the rest is history. Rajapaksa himself was almost a victim of a similar bomb attack a few months later in December 2006 but escaped unhurt. Fonseka and Rajapaksa teamed up to crush the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in May 2009 but they parted ways when Fonseka contested Mahinda Rajapaksa at the presidential election. They are now in opposing political camps.

Nevertheless, that anecdote captures the essence of what Gotabaya Rajapaksa is supposed to be about: someone who got the job done and someone who brooked no nonsense in that process–and that was how he was marketed to the Sri Lankan electorate at the presidential election held one year ago.

Candidacy

When Gotabaya Rajapaksa was announced as the candidate for the newly formed but popular Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP) better known by its symbol as the ‘pohottuwa’ party, he was the least experienced in the hurly burly of politics among the Rajapaksa brothers, but with elder brother Mahinda disqualified from running for a third term, Chamal not interested and Basil refusing to give up his US dual citizenship, it was his call to make.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s critics did question his credentials. How could he, without any political experience at all, lead a country that has always been led by career politicians with the exception of Sirima Bandaranaike, they asked. In the US, a similar novice had assumed the Presidency and making a mess of things. His military credentials cut both ways; efficiency on the one side, military rule on the other.

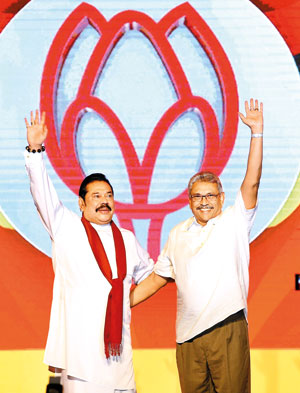

Entry into mainstream politics: Gotabaya Rajapaksa being presented as Pohottuwa's presidential candidate at the party's inaugural convention last year

Colonel (Ret.) Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s ambitions to aspire for the highest office did not come about overnight or by default. Ever since Mahinda Rajapaksa was ousted from power in January 2015 and the return of Basil Rajapaksa to Sri Lanka after a period of self-imposed exile in the United States, he carefully laid plans for a political role, that of a technocrat-politician; someone who would “drain the swamp” and do it differently.

It was no coincidence that ‘Gota’, as he was called, was a patron of sorts to two organisations, ‘Viyath Maga’ and ‘Eliya’, both of which espoused the participation of more professionals in politics. There seemed some early hesitation, even from the family, to name him. When asked, the party hangers-on were told by the family to wait for the announcement. The only certainty was that “it will be a Rajapaksa”. In October 2018, brother Mahinda was made Prime Minister in a notoriously dumb political exercise that came a cropper. But it showed that Gotabaya’s plans nearly got jettisoned in the process. Inevitably though, by end 2019 and a Presidential election looming, he was the only choice left, at least for the next national elections.

Less than a week after over 250 people were killed in several bomb attacks on churches and hotels on Easter Sunday, 2019 Gotabaya Rajapaksa publicly announced that he would run for President. National security became the topmost item on the country’s agenda. It was the perfect cue for the war-winning former Defence Secretary to enter the political stage; ‘Cometh the hour, cometh the man’.

There remained one hurdle to clear, the renunciation of his dual citizenship in time. The political tide had by then turned. The ‘Good Governance’ Government of 2015 had become dysfunctional. The two main parties that formed it in attrition, both with each other and within. Brother Mahinda was immensely popular in the southern heartland, the Buddhist clergy and rural voters carrying him on their shoulders, and he carrying Gotabaya on his waving the nationalist flag with all four hands.

Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s victory was convincing: 52 per cent of the vote and 1.3 million votes more than Premadasa. The only hint of dissent came in the polarising nature of the vote: regions dominated by ethnic minorities–the North, East and the Nuwara Eliya district–voted for Premadasa, all other regions backed Rajapaksa. That the vote was delineated on ethnic lines was no secret.

Presidential office

As President, Gotabaya Rajapaksa has made no apologies for this either. After his swearing-in at the Ruwanveliseya in Anuradhapura he was to note that he won with “only the votes of the Sinhalese majority”. “I asked Tamils and Muslims to be a part of my success. Their response was not what I expected. However, I urge them to join me to build one Sri Lanka,” the newly elected President said.

One year on, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa has had an eventful period in office. Hardly ensconced in office, he had to deal with a global pandemic, likes of which has not been witnessed in living memory. It was a baptism of fire for the soldier turned politician, a new war to be waged. Fortunately, he didn’t have to work with a Prime Minister or government not of his choice. Still, he felt straightjacketed by the 19th Amendment and wanted all powers to be vested in him. He was impatient to hold a parliamentary election and got what he wanted–a magical two-thirds majority in the House in a benign political environment with a divided and demoralised Opposition. Now, he had everything.

In the time that he has been Head of State, Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s style has been different. Unlike brother Mahinda, the quintessential politician, the President is not the ‘hail-fellow-well-met’ type who pats you on the back and makes you feel instantly comfortable. His public appearances are few and far between. He is not given to spouting rhetoric from political platforms. And yet, his personal stock with the public rose so high in the first eight months, partly due to his seemingly successful navigation of the pandemic that ‘his’ novice candidates for Parliament (rather than the dyed-in-the-wool politicians who were brother Mahinda’s sidekicks) got majorities over and above the veterans, As much as the electorate gave the SLPP a two-thirds, it also gave a secondary message to the ‘old crocks’, if not ‘old crooks’ who were returned to Parliament with dodgy track records from the past.

It is an understatement to say that President Rajapaksa has had his task made easier by the nominal nature of the political opposition he faces. The UNP has been virtually wiped out and is vacillating on filling the solitary National List seat they are entitled to in Parliament. The newly formed Samagi Jana Balavegaya of old UNPers is yet to make its presence felt and its captain Sajith Premadasa is still finding his feet as Leader of the Opposition.

It is an understatement to say that President Rajapaksa has had his task made easier by the nominal nature of the political opposition he faces. The UNP has been virtually wiped out and is vacillating on filling the solitary National List seat they are entitled to in Parliament. The newly formed Samagi Jana Balavegaya of old UNPers is yet to make its presence felt and its captain Sajith Premadasa is still finding his feet as Leader of the Opposition.

With the unseen hand of brother Basil by his side, the passage of the 20th Amendment–which has drawn fire from many quarters–restores powers that were disseminated to Parliament back to the President and reverts the Presidency to an age reminiscent of the J. R. Jayewardene era. Indeed, the political landscapes of the Jayewardene and Gotabaya Rajapaksa presidencies are eerily similar: a President who is not shy to wield power and have control over government, a subservient Parliament with a steamroller majority for the ruling party and a weak and emaciated opposition–and a President who wants to change the ‘old order’. Rajapaksa is seemingly turning the clock back to the Jayewardene era forty years ago.

The President now has the powers to hire and fire Prime Ministers and ministers, Supreme Court judges and the Attorneys General, the heads of the Police and the Armed Forces, Elections Commissioners, Ministry Secretaries, Ambassadors–in other words, the entire ensemble of government.

There are also concerns that, with the President being armed with such power and authority, there would be a tendency for the country to veer away from the hoped for meritocracy into an oligarchy, already dominated by one powerful family, even though they may be elected to office.

If President Rajapaksa has been successful so far in taking control of the state apparatus–he must know that, four years from now, when the people will judge him on his performance, the buck stops with him: any credit or blame will solely be his, the somewhat fading shadow of elder brother Mahinda notwithstanding.

An allegation that was often made against the previous Rajapaksa regime–headed by Mahinda Rajapaksa–was cronyism to such an extent that loyalists considered themselves to be above the law. This led to much resentment among the public and President Gotabaya Rajapaksa would do well not to repeat that mistake, although some warning signs have already emerged.

Persons close to him may take advantage of past association, while others are complaining that he is now cut away from their reach and not returning their calls. This is a recipe for disaster. As much as requesting he not be invited for every wedding in town is commendable, the Executive Presidency is an ivory tower, an ideal place to lose touch with reality, cocooned in office as it were, surrounded only by a coterie feeding him ‘dead ropes’ as President R. Premadasa suddenly discovered to his horror.

Dealing with the pandemic

Recent setbacks in the control of the COVID-19 pandemic has dented the President’s image. With the pandemic threatening to escalate and cracks appearing in the strategies adopted to deal with it, the President is relying more and more on the Army to stem the tide. Medical experts bemoan the fact that they are being called upon to implement policies emerging from the military rather than vice versa. There does not appear to be a single, coordinated approach from the various arms of the government to deal with the pandemic. The sorry spectacle of the Minister of Health throwing a pot of ‘holy water’ into a river to obtain divine help and a miracle cure does not inspire public confidence that the Government has things under control.

Admittedly, the Government has shifted gears in dealing with the pandemic. The lockdown and curfew is getting changed by the day as the Government tries to balance public health with the deteriorating economy. More and more reliance is being placed on the military and retired Majors Generals that is attracting the wrath of the public service that is ganging up in a show of passive resistance to change. The frustrations of the President are understandable.

That the President is hamstrung by an economy that was in a hospital ward now in the ICU. With a global recession due to the pandemic, Sri Lanka’s ‘debt crisis’ has got compounded propelling the country backward o the pre-1977 era of import substitutions. While closing the economy on the one-side it is relying on foreign aid, and even more loans to stay afloat. Over-reliance on China for a bail out and ‘secret calls’ with the Chinese President fuel speculation that the country is drifting too much into the Dragon’s claws. All this is not entirely President Rajapaksa’s fault but as the Chief Executive of the country, it will become his task to provide some form of redress- and the blame too will be his if he is unable to meet this challenge.

Challene ahead

Meanwhile, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa is focused on redefining the Executive Presidency, and not in abolishing it as has been the public outcry for decades. In so doing, he should also realise that the new Constitution he wants drafted and the Presidency he creates therein may also, some day, be in the hands of his political opponents. J.R. Jayewardene, one can almost be certain, wouldn’t have imagined that the Constitution he created would have benefited the Rajapaksa family of Medamulana.

Critics of the President have said that he cannot achieve the ‘system change’ he promised by one visit to the office for the Registration of Motor Vehicles (RMV) at Werahera and that is probably true. The public service is far too underpaid, and corrupt for that. However, he is still perceived by the public as a leader who wants to make changes for the better and is clearly sincere in his intentions.

To do so, he needs to beware of the ‘usual suspects’ who lead to a politician’s downfall: cronies and sycophants who sing only his praises, businessmen who want to make a fast buck and politicians and other hangers-on who think only of their survival, not that of the nation.

Surrounded and blinded by these types, even a politician as savvy and street-smart as Mahinda Rajapaksa couldn’t recognise that his popularity was slipping until the election results trickled in on the morning of January 9, 2015. With the benefit of such hindsight, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa would do well to do what he does best: govern with clinical efficiency and single-minded determination to ensure a better nation for all by the end of his tenure.

While it has been said that a politician thinks of the next election, a statesman thinks of the next generation. In that sense, not being a politician all his life, it would be easier for President Gotabaya Rajapaksa to think of the next generation as he completes his first year in office and contemplates the challenges ahead in the coming four years. Perhaps his thoughts should be, “mata mey rata berala oney” or “I want this country saved”–the only difference is, this time he would have to do so mostly by himself.