Poor pay more taxes?

View(s):

Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa presenting the budget in Parliament.

There is a popular saying, particularly during the time the government’s budget is presented, that “the poor pay more taxes than the rich” in Sri Lanka. Whenever I heard it, I had a question: How is it possible? I thought of worthwhile noting it at the outset for our discussion today, not just to answer this question, but since it directs us to recognise some deeper issues, perhaps going beyond economics to politics as well.

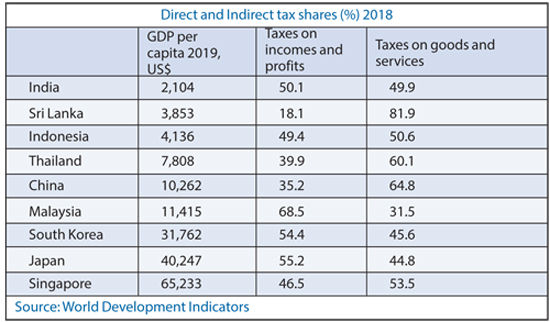

The claim is based on direct – indirect tax shares of Sri Lanka. Direct taxes are the taxes applied on incomes and profits, which contribute about 20 per cent of the total tax revenue of the government. Indirect taxes are those applied on goods and services, such as VAT, import duty and other, which contribute about 80 per cent of the government’s total tax revenue. The notion that the “poor pay more” is based on this 20:80 share of direct-indirect taxes. But is it true?

Direct taxes are paid by “income-earning” persons, while usually the higher the incomes, the greater will be the tax rates. In the case of indirect taxes, if a rich person and a poor person both go to purchase the same commodities in similar quantity, then the amount of indirect taxes paid by both would be the same. However, the poor person usually spends more on “basic needs” such as food stuff which are taxed at lower rates. The rich person spends on higher value commodities which are taxed at higher rates. Then actually the rich person still spends more than the poor. These examples clarify the fact that it is difficult to prove the claim that the “poor pay more”.

The only possibility for taxes paid by the poor to be more than that paid by the rich can depend on the share of poor in the country. Nevertheless, how can we say that it is the poor who spend more than the rich on purchasing goods and services? The number of poor persons in Sri Lanka is less than 850,000, according to the national poverty line of Rs. 4,166 as the minimum requirement of real expenditure per month. If we consider the World Bank’s “lower middle-income” poverty line, there are still 2.3 million people in the country earning less than US$3.20 a day, which is about Rs. 600. If it is the “upper middle-income” poverty line, then there are almost 9 million people earning less than US$5.50 a day, which is about Rs. 1,000. There is no doubt this is an overwhelmingly large poor segment with lower income. However, this means that still the balance of the population share out of 21.5 million people is larger than the number of poor so that even by looking at the share of poor it is difficult to qualify the statement that the “poor pay more taxes”.

Underdeveloped features

of development

Despite all that, the direct-indirect tax shares of 20:80 shows a major weakness in the tax system, because it is a result of the fact that the government doesn’t know the income and wealth of the citizens. Basically, it is a characteristic of an “underdeveloped” country. It is bizarre to say that even after being elevated to a “middle-income country”, Sri Lanka’s tax system shows characteristics of an underdeveloped country.

The world experience shows that most of the progressive countries have improved their direct tax contribution and surpassing 40 per cent or even 50 per cent. An interesting example is India, which has much lower GDP per capita than Sri Lanka and, which has not yet elevated to a “middle-income” status. At the time of embarking upon its policy reforms in 1990, India also has direct-indirect tax share as 20:80; within less than 20 years, India was able to change it gradually to 50:50 and sustained it thereafter. The experience of India shows that even before reaching the higher-income status, a country can change the direct-indirect tax shares through changes in policies and regulations.

There are a number of reasons for the continuous existence of a direct-indirect tax ratio as 20:80. The first is the lack of a proper centralised database system: This has basically two dimensions as to maintain citizens’ income and wealth on the one hand, and, to maintain the country’s business activities on the other hand. It is true that citizens’ information is fed into digital databases at various agencies for different purposes, but there is no “centralised” information system. Even the business activities are reported and recorded at various national and local levels, but there is no proper centralized database of the business activities of the country. For me it’s a question as to why Sri Lanka has so far failed to implement a centralised database for citizens and for their economic activities.

Multiple issues

The result of this failure is that the government doesn’t have the information on each and every citizen’s income and wealth as well as the information on each and every business activity operating in the country. Obviously, when there is no proper information on people’s “earnings” the easier option available for the government is collect taxes at the point of “spending”. As a result, the government budget has to depend overwhelmingly on indirect taxes.

This is, however, not the whole story. When there is no centralised information on people’s income and wealth, the space for tax evasion is large too. When the tax revenue becomes smaller and the expenditure requirement larger, the government has to rely more and more on the same indirect taxes. This is the reason for the existence of multiple and complex taxes on goods and services, including tariffs plus various para-tariffs on imports to cover the government’s revenue requirement. The lack of a centralised information system on people’s income and wealth leaves space for corruption and bribery too because there is no general requirement to show the source of funds.

This is, however, not the whole story. When there is no centralised information on people’s income and wealth, the space for tax evasion is large too. When the tax revenue becomes smaller and the expenditure requirement larger, the government has to rely more and more on the same indirect taxes. This is the reason for the existence of multiple and complex taxes on goods and services, including tariffs plus various para-tariffs on imports to cover the government’s revenue requirement. The lack of a centralised information system on people’s income and wealth leaves space for corruption and bribery too because there is no general requirement to show the source of funds.

It should be noted that policy reforms towards a market-economy, as I have always emphasised, did not take place through a “holistic approach” thus there are many areas which were left intact. Consistent fiscal policy reforms are some of these areas which continued to be left intact. If not for that weakness, distorted direct-indirect tax share would have changed along with progressive economic changes of the country. As a result, the deficient factors have been left behind and they continue to deter the progressive economic path of the country, creating space for many other economic and political issues, including those of the fiscal policy management.

Budget 2021

Budget 2021 is, perhaps, the most challenging budget in Sri Lanka’s post-independent history. The tax revenue is down due to lower incomes and lower demand for goods and services on the one hand. The expenditure is up due to government’s extensive support required for stimulating the economy. The result is that the budget deficit is higher than before, and the need for debt-financing is greater too. There is nothing unusual here, because generally it is a global situation in every country which has faced with an economic crisis.

However, as we have discussed today, part of the Sri Lankan problem is much more deep-rooted than the impact of the economic crisis that the country is faced with. I believe this is a good time to embark on a centralized information system for people as well as for businesses, which has multiple purposes and multiple benefits for the economy and for governance.

By the way, I came to know that the population census of the country which has been taking place usually with 10-year intervals is planned for 2021. With today’s technology, information may be just a mouse-click away any time of the year, if the country has established a centralised information system for its citizens.

(The writer is a Professor of Economics at the University of Colombo and can be reached at sirimal@econ.cmb.ac.lk and follow on Twitter @SirimalAshoka).