Let the leopard roam

However, there are still multiple reasons to be concerned about its long-term future on the island. After all, Vulnerable status still means that some combination of a species’ population size, population size change, distribution and threats that make it a “high risk of extinction”. For the Sri Lankan leopard, the basis for this is its small population size which is estimated to consist of < 1000 mature individuals.

It may strike many as incongruous that this status change is taking place in a year that has seen a high number of individual leopard deaths (13 and counting) as well as what appears a disconcerting increase in land grabs and forest clearances (e.g. Anavilanduwa, Flood Plains NP, Gal Oya NP boundary buffer, Sinharaja road construction) which is effectively reducing the amount of available habitat for wildlife. For these reasons, and others that we will expand on below, it is important to carefully monitor the leopard in Sri Lanka, to ensure that it does not rapidly slip back into the Endangered category, which implies a “very high risk of extinction”.

Mother and cub living along a ridge corridor in the Central Highlands

As the IUCN assessors for the Sri Lankan leopard, we worked with the IUCN head office in Switzerland to ensure a built-in mechanism allowing for rapid re-assessment if apparent trends suggest this is necessary. A key reason for the status change is the unusually extensive information that we now have about the leopard in Sri Lanka, due to numerous studies in a variety of habitat types with varying levels of protection, which allows for a detailed and nuanced population estimation. The new population estimate and range extent upon which the status change was predicated, arose from this increased knowledge and not simply from a straight comparison of a population “before and after”.

Future steps

What does this mean for the long term viability of leopards in Sri Lanka? First, it is worth recognizing that things might not be quite as bleak as they appear, for leopards are remarkably adaptable creatures that can, and regularly do, alter their behaviour and patterns of activity to ensure co-existence with humans. Given leopard social structure, which is both solitary and territorial, when an individual leopard is killed there is typically another animal ready to occupy the newly vacant territory – possibly an animal that otherwise might never have been able to establish a territory of their own. This, of course, is not to say that individual animals being killed is unimportant, only that below a certain threshold it need not have population-level effects. However, there do exist numerous increasing threats – direct and indirect – that need to be countered quickly in order to ensure that the leopard remains a key member of the island’s much-vaunted biodiversity long into the future.

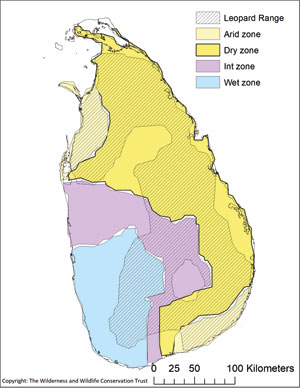

This desire to ensure the long-term survival of the Sri Lankan leopard is not simply for its intrinsic, iconic value as a stunning example of an organism finely honed by millions of years of evolutionary pressures – although that alone is a pretty decent reason – but also for its ecological and biodiversity value. The leopard is an ideal “umbrella” species because it is wide-ranging and lives in all habitat types, so protection of habitat sufficient to ensure a viable leopard population will, by default, ensure the concurrent conservation of much wider biodiversity. Furthermore, the leopard sits at the apex of the food chain, and may be a keystone species acting to regulate prey populations with subsequent cascading effects onto lower trophic levels (i.e. vegetation). Finally, there is an argument to be made regarding the economic value of the leopard from the perspective of tourism.

This desire to ensure the long-term survival of the Sri Lankan leopard is not simply for its intrinsic, iconic value as a stunning example of an organism finely honed by millions of years of evolutionary pressures – although that alone is a pretty decent reason – but also for its ecological and biodiversity value. The leopard is an ideal “umbrella” species because it is wide-ranging and lives in all habitat types, so protection of habitat sufficient to ensure a viable leopard population will, by default, ensure the concurrent conservation of much wider biodiversity. Furthermore, the leopard sits at the apex of the food chain, and may be a keystone species acting to regulate prey populations with subsequent cascading effects onto lower trophic levels (i.e. vegetation). Finally, there is an argument to be made regarding the economic value of the leopard from the perspective of tourism.

From two decades of leopard research in Sri Lanka complemented by lessons learned in other systems and extensive research by others around the world, there are a few key areas that are of particular importance for leopard conservation here. Broadly, these are 1) ensuring adequate habitat quantity, 2) ensuring adequate habitat quality, and 3) fostering the co-existence paradigm.

Ensuring adequate habitat quantity

Simply put, wildlife requires space for its well-being, and leopards are no different. Although remarkably adaptable predators, famous for occupying even the most marginal lands, leopards nevertheless prefer certain habitat types, thriving in some areas while merely surviving in others. In Sri Lanka, our research has shown that forest cover and the level of protection of the landscape improve habitat suitability for leopards. This means that the goal of maintaining 30% forest cover across the island is a key one for long-term leopard viability here.

It is not simply forest cover that is important however, but its configuration, with a workable framework consisting of sizeable core areas (e.g. protected areas such as National Parks) connected via a network of forest corridors. The most appropriate core areas should be solid, contiguous blocks similar to the Wilpattu and the Yala complexes, as this structure reduces the impact of edge effects by allowing for a secure interior even if the boundary areas are penetrated by activities that increase risk. Our research has revealed that edge effects are already experienced by leopards in Wilpattu NP as evidenced by their avoidance of boundary areas in favour of the central portion of the park, even after accounting for the prey availability differences between these areas. Long, thin parcels of land are much easier to breach and are therefore of higher risk, but these are still of key importance as connecting corridors between core areas. As solitary, territorial animals, leopards require dispersal routes allowing them to move from natal ranges to other areas where they can attempt to establish themselves. Without relatively low risk connections between habitat patches there is a reduction in the ability of individuals to disperse, resulting in overcrowding which can cause increased intra-specific competition (fighting amongst individuals) as well as isolation of sub-populations which increases the risk of inbreeding, since close relatives cannot move away. The absence of connections between core patches will ensure that the Sri Lankan leopard rapidly returns to Endangered status. Ideally, wide, forested tracts of land that run between core habitat patches is best, however even narrow protected corridors or even a “stepping stone” configuration of small forest patches can work to allow this vital movement. Thus, it is a holistic, landscape-level approach that needs to be taken when planning future leopard management.

Ensuring adequate habitat quality

Adequate habitat is the first step, as it is imperative that this habitat be of sufficient quality to allow for leopards to secure prey, reproduce and rear cubs. Asia is beset by the “empty forest syndrome” particularly in the south-east and far east, with areas of forest cover that are denuded of their wildlife, usually due to poaching. Flying over these forested areas, one would assume a thriving biodiversity within, but often they stand bereft of birdsong, the leaves rustled only by the passing wind. It is essential that Sri Lankan forests – which still do teem with life including a viable prey base for leopards – remain that way, with protected areas well protected and illegal incursions by people minimized, particularly those who are intent on poaching or felling trees. In the absence of sufficient wild prey, leopards will look elsewhere for sustenance, including towards livestock grazing along forest edges, a high risk endeavor that endangers both rural communities and the leopards themselves.

Fostering a co-existence paradigm

Sri Lanka has a long history of human communities co-existing with wildlife, with the numbers of wild elephants and leopards still extant here despite a dense, highly rural human population perhaps the clearest example of this impressive ability. This remarkable feature of life in Sri Lanka needs to be fostered as it will only be required more in the future.

It is easy to say that people must be willing to share space with apex carnivores to ensure the latter’s long-term survival, but it is much more difficult to do, with rural communities the ones required to actually enact this idea. To ensure that co-existence remains a viable approach, negative human-wildlife interactions must be minimized, so people living at the human-wildlife nexus also thrive. This means reducing the scenarios that could give rise to negative human-wildlife interactions,and the creation and incorporation of mitigation measures when necessary, including inculcating an understanding of leopard ecology and behavior in order to avoid problems.

Summary

A reasonable protected area network already exists in the lowland dryzone, but increasing the amount of protected area in the Central Highlands and lowland wet zone is necessary. The recent gazetting of additional forest area around Sinharaja is a promising step in this direction. Also of critical importance is to identify, restore if necessary, and actively protect connections between existing forest patches to ensure wide-ranging species like the leopard do not become a series of isolated sub-populations. People living along these corridors must be supported when necessary and encouraged to maintain the long-held co-existence paradigm that has allowed Sri Lanka to remain a relative bastion of biodiversity in the world. This method can ensure the continued survival of leopards and other wildlife in Sri Lanka.

( The authors are IUCN Species Survival Commission Members & Red List Assessors, lead Scientist/Founding Trustees, Wilderness & Wildlife Conservation Trust, The Leopard Project, Sri Lanka -wwct.org, info@wwct.org/akittle@wwct.org/awatson@wwct.org)