News

An opportunity to harvest Indian Ocean yellowfin tuna sustainably

On the last day of 2020, the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC) published a circular that sets out annual catch limits for Indian Ocean yellowfin tuna (kelavalla/Thunnus albacares) in the seas beyond national jurisdictions. Accordingly, Sri Lanka’s annual yellowfin tuna catch limit in the seas beyond the country’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ) has been reduced from 7,762 metric tonnes (MT) in 2016 to 5,302MT in 2021. The 2,460MT reduction is a consequence of IOTC Resolution 19/01 – on an interim plan to rebuild the status of Indian Ocean yellowfin tuna stocks.

An immature (5 kg) and mature (46 kg) yellowfin tuna caught in 2019

The interim plan was adopted by IOTC members in 2016. The resolution was formulated in response to advice from international fishery experts who called for a 20 percent reduction in the catch of Indian Ocean yellowfin tuna (about 80,000MT) to rebuild the status of the stocks to a sustainable level by 2024. The IOTC’s assessment of Indian Ocean yellowfin stocks in 2015 suggested that stocks were overfished (not enough mature fish in the sea) and subject to overfishing (too many fish being caught).

The conservation management measure introduced by the IOTC in 2016 (i.e. catch reductions) has been poorly administered over the intervening three years. Many Indian Ocean coastal states, including Sri Lanka, and distant water fishing nations reported catches above the IOTC’s annual limits in 2017, 2018 and 2019. One reason is that the IOTC has no legal hold on IOTC members, which are sovereign states. The IOTC’s mandate is to promote cooperation among member states to ensure the conservation and appropriate utilization of fish stocks while encouraging the sustainable development of fisheries. Enforcement – when it happens – is usually through the backdoor; by third parties using non-compliance as the basis to leverage trade sanctions against countries that fail to comply with IOTC Resolutions. International non-governmental organisations also play an enforcement role by urging consumers, retailers and wholesalers in Europe and North America not to buy yellowfin tuna products from countries with poor compliance records.

In March this year, IOTC fisheries experts will meet to discuss their approach to the upcoming stock assessment. In September, the results of the assessment will be announced. The IOTC’s Scientific Committee will debate the results in November. Resolution 20/01 is to be formulated and is almost certain to contain new, more stringent conservation management measures to rebuild the Indian Ocean yellowfin tuna stocks.

For Sri Lanka’s yellowfin tuna fisheries, 2021 will be a critical year. Yellowfin tuna exports were worth US$ 160 million (Rs 23 billion) in 2019; more than 20,000 fishermen are directly engaged in multiday boat fishing; more than 10,000 women are employed in the seafood processing industry. How Sri Lanka responds to the challenges that are to come this year will have wide ranging impacts on employment, household incomes and export earnings for the rest of the decade.

The IOTC’s response to the 2015 stock assessment (i.e. catch reductions) might, if applied effectively, eventually lead to a sustainable fishery. If the catch is reduced enough, the stock will cease to be subject to overfishing. There will be enough mature fish in the sea and the fishery will be sustainable. The yield will of course be 10%, 20% or even 30% less than the maximum sustainable yield (about 400,000 MT). However, as we have seen over the last three years, effective implementation of catch reduction hasn’t happened.

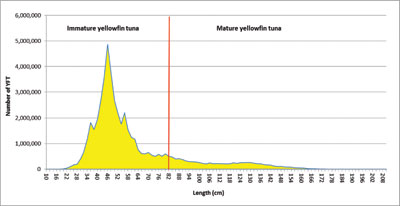

Last year my colleague Eranga Gunasekera and I used length, weight and catch data collected by the IOTC between 1955 and 2015 to look at the impact of different fisheries – pole and line, handline & trolling, longline, gillnets and purse seine – on the yellowfin stock. The results were surprising. About 50% of the yellowfin tuna caught by Indian Ocean fisheries in 2015 were immature (<82cm). The average weight of a fish was around 5 kg. Yellowfin tuna are big fish that grow up to 200 cm and can weigh more than 180 kg. Recently we updated our analysis using length, weight and catch data collected by the IOTC in 2019. The new analysis suggested that more than 80% of the catch was made up of ‘baby yellowfin tuna’ (see Figure 1).

Theoretically a fishery can be sustainable even with 80% immature fish in the catch. But, the total yield will be much less than maximum that is sustainable and the value of the catch will be much less than the maximum economic yield. Our recent analysis suggests that if 80% of the yellowfin tuna caught were mature (about 35 kg) then the fishery would be worth US$ 600,000 million more than the fishery is now, because the current fishery is focused on harvesting immature fish.

A challenge can sometimes be reframed as an opportunity. The opportunity inherent in the current – overfished and subject to overfishing – status of the Indian Ocean yellowfin tuna is to refocus fishing effort away from harvesting large quantities of low value baby yellowfin tuna, towards fisheries that harvest lower quantities of high value adult fish. In the short term IOTC’s Circular (2020-55) and Resolution 19/01 mandate an immediate reduction in Sri Lanka’s beyond EEZ yellowfin tuna catch. Failure to comply will raise the specter of seafood sanctions and iNGO disapprobation, while compliance will reduce the quantity of fish caught, livelihood opportunities and the value of seafood exports: heads you lose / tails you lose too.

Figure 1 Lengths of 50 million yellowfin tuna caught by all Indian Ocean fisheries in 2019

Resolution 20/01 is an opportunity to move beyond the misguided mantra of ‘catch reduction’; to introduce new conservation management measures that will reduce overfishing of baby yellowfin tuna. If less immature fish are caught, more will mature. Pretty quickly there will be enough mature fish in the sea to harvest the maximum sustainable yield, indefinitely.

(Steve Creech is a freelance fisheries consultant and the director of pelagikos private limited. steve@pelagikos.lk)