Sunday Times 2

Singaporean More or Less

View(s):Reviewed by David Robson

This book is much more than a straightforward monograph on the work of Mok Wei and ‘W Architects’. It celebrates Mok’s long association with William Lim, his erstwhile employer, mentor and partner, recounting the prehistory of the practice that Lim founded and subsequently handed over to him, and provides us with an account of the unfolding story of architecture in modern Singapore. And, just as Mok’s stated aim is always to generate a building’s design from its context – whether physical, environmental or cultural – so the book sets out to place the work of W Architects in its wider intellectual context. As well as describing his buildings, it also explains the thinking behind them.

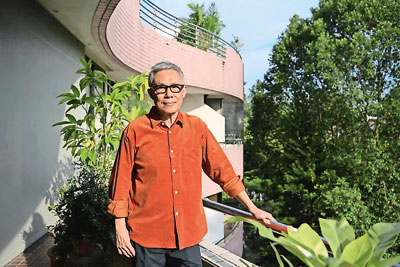

Veteran Singapore architect Mok Wei Wei. Pic courtesy Strait Times/NG SOR LUAN

The book begins with a reflective introduction by Chang Jiat Hwee which traces Mok’s personal development through the turbulent decades that followed the founding of the island republic. The three main sections of the book are then headed by contemplative essays by Mok himself. The first describes his search for fundamentals and his fascination with duality. It features projects that he designed with William Lim, first as an assistant, and later as his partner, and charts Lim’s seemingly frantic search for an alternative Asian modernism.

The second focuses on the context of Singapore and describes a series of residential projects carried out within its tight regulatory environment. The third charts Mok’s personal search for a contemporary architectural language which could reflect the histories of the different communities that make up what has become a global city-state and ends with descriptions of three major public buildings.

Mok Wei Wei is Singaporean, through and through, but remains conscious of his Chinese roots. He was born in Singapore in 1956 and was nine when Singapore broke away from the Malayan Federation. His father was a journalist on a Chinese-language newspaper and moved in Chinese artistic and literary circles. Mok grew up in a world populated by artists and writers and was bilingual in Mandarin Chinese and English. He studied in Singapore at the National University (NUS) School of Architecture, qualifying in 1982 and all of his built projects have been realised in Singapore.

Almost immediately after qualifying in 1982, Mok joined William Lim Associates (WLA), a practice headed by William Lim, one of the island’s pioneering architects and leading intellectuals, and went on, ten years later, to become Lim’s partner. After Lim’s retirement in 2003, the WLA practice was dissolved and Mok formed ‘W Architects’, a name that references both his own initials and those of his mentor.

William Lim belonged to the pioneering generation of Singapore architects whose careers kicked off at the same time as the founding of the Singapore Republic. A great networker, he developed a global outlook and was tuned-in to the latest developments — political and cultural as well as architectural — in Europe and the United States. This meant that he was able to keep abreast of the latest ideas, but it also made him susceptible to passing trends and fashions.

Lim was one of the founders of the Malayan Architects Co-partnership (MAC) which in 1961 was responsible for designing the NUTC conference hall, a ground-breaking essay in abstract modernism. In 1964 he was a founding member with Tay Kheng Soon of the Singapore Planning and Urban Research Group (SPUR), a ginger group which set out to question and influence government planning policies and from that time, was as much a polemicist and writer as an architect.

When MAC broke up, Lim joined with Tay to form Design Partnership (DP). In a brief period of intense creativity Lim and Tay built two ground-breaking modernist monuments: the People’s Park (1970), a high-rise slab block perched above a mixed-use podium on the edge of China Town and the Woh Hup Complex (1974), a canted mega-structure on the eastern edge of the city.

In 1976, Lim’s wife Lena opened a shop called Select Books, and started to publish books on a range of subjects including architecture. Over the next three decades this publishing venture placed the Lims at the intellectual centre of Singapore, providing them with a network of contacts across the whole of Southeast Asia. It also furnished Lim with a platform from which to launch a series of polemical books about Asian urbanism, as well as a book entitled ‘Contemporary Vernacular’ (1998) which set out his arguments for a contemporary Asian architecture that embraced local traditions.

The years after independence had witnessed a massive development effort in Singapore. The Housing Development Board (HDB) had produced impressive numbers of affordable homes both within the city and in new satellite towns, though their architectural and urban design quality was sometimes disappointing. At the same time many commercial and public buildings were being entrusted to foreign ‘starchitects’ who often operated with scant regard for local values. Disillusioned with the bland modernism that held sway across the island, Lim started to look around for alternatives. In 1981 he quit Design Partnership and set up William Lim Architects (WLA) with a group of young assistants that included Mok Wei Wei.

Experiment with fragmentation

Lim’s search took him simultaneously in a number of different directions. His acquisitive mind had already led him to experiment with Post-Modernism during his final years in DP. On a visit to Los Angeles in 1982 Lim and Mok met the American architect Frank Gehry, who had been Lim’s contemporary at Harvard. This led them to experiment with fragmentation and resulted in their design for a community centre in Tampines New Town. This deconstructs the constituent elements of a community centre and places them like broken shards within the armature of a formal perimeter arcade, creating a web of fractured alleyways.

Lim also developed an interest in the ‘adaptive re-use’ of old buildings. Working with Mok, he produced detailed proposals for the renovation of a large section of the Boat Quay and went on, with three separate colleagues to produce designs for three shop-house transformations on Emerald Hill. These, in turn, led to a number of designs for houses, such as the Reuters House (1990) that played subtle deconstructive games with traditional local and colonial forms.

By the end of the 1990s, Mok’s designs for two houses signalled that he and Lim were moving in different directions. The Lem House (1995-97), which appears at the end of the first section in the book, employs fragmentation to express its constituent parts and to respond to its context, but maintains a clear orthogonal geometry and adopts the language of abstract modernism.

The Morley Road House (1966-69) leads the final section of the book and was inspired by Mok’s interest in Chinese architecture. Early in his career he studied the garden-houses built by educated mandarins during Ming dynasty in south-eastern China and was fascinated by the contrast between the formal ordering of the buildings and the organic and consciously picturesque quality of the landscape. Mok’s design creates a series of interconnected pavilions and open spaces that are organised around a central pool defining a meandering promenade through a sequence of expanding and contracting volumes. However, while the spatiality was inspired by Chinese precedents, the architectural language followed the cool abstraction of the Lem House.

The second part of the book includes a series of designs for medium and high-rise condominiums. The vast majority of Singaporeans live in public housing, while a small privileged minority live in ‘landed houses’. Most of the rest live in private condominiums. The scarcity of land has forced developers to build these to ever greater heights and higher densities. Singapore is strictly zoned and building is regulated by complex rules that determine floor-area-ratio (FAR). A key part of the design process for Mok was navigate the regulatory system to arrive at optimal architectural solutions.

Mok’s first such project, ‘The Patterson Edge’, designed in 1996 occupies a long narrow site close to Orchard Road and takes the form of an eight-storey block behind a sheer curtain wall-of glass shielded by elegant metal sun-breakers. The entire roof, usually given over to services, is set out as a terrace with a pool that enjoyed views across the city.

Another, known as ‘The Loft’, places three four-storey blocks around a garden court with a swimming pool, providing an oasis of tranquillity on the edge of the central shopping district — a scaled up version of a Chinese garden-house.

Perhaps the most startling original of the series was the Oliv, designed in 2007 for a site on Balmoral Road. This twelve-storey development consists of two linked blocks with pairs of duplex apartments each sharing a double-height floor plate.

Apartments open on to two-storey high garden-terraces that are theoretically classified as communal in FAR calculations, but are in fact private. Each apartment creates the illusion of being a bungalow in the sky. The core of the apartment block is designed in a strictly orthogonal manner like a complex three-dimensional labyrinth, while the garden terraces are ‘planted’ on to the facades like geo-morphic eruptions, recalling the contrast in the Chinese garden-houses between the formality of the buildings and the organic quality of the gardens.

Singapore lies close to the equator and experiences high temperatures, high levels of humidity and heavy rainfall. Mainland China, in contrast, lies to the north of the Tropic of Cancer, and the Chinese, like British, are not suited to life on the equator. Prime Minister Lee Kwan Yew hailed the air-conditioner as one of the greatest inventions of the 20th Century and Singaporeans now live, work and play under air-conditioning.

Mok designs with climate in mind, but he does not treat climate as a primary generator of architectural language. Air-conditioning brings many benefits, but it produces a number of negative side-effects, which he tries to mitigate. He creates naturally ventilated transition spaces and introduces shading devices and planting beds to break down the barriers between inside and outside that air-conditioning inevitably imposes.

This approach is demonstrated in Mok’s 2008 design for an ‘Education Resource Centre’ on a northern extension of the National University’s Kent Ridge campus. To save as many trees as possible, he proposed a sinuous two-storey ‘ground-scraper’ that echoed the contours of the site and snaked its way around the trees underneath a green roof. Broad horizontal baffles shut out direct sunlight while reflecting indirect light and encouraging ventilation, enabling him to reduce the air-conditioned volume by a third while creating seamless connections between internal and external spaces.

Reconfiguration of iconic buildings

The third and final section of the book ends with descriptions of three important public commissions. Two of these involved the reconfiguration of iconic institutions from the colonial period: the National Museum of Singapore at the foot of Fort Canning and the Victoria Theatre and Concert Hall at the mouth of the Singapore River. In both, Mok effortlessly adapts existing buildings to support new functions and, demonstrating skills that he honed in his earlier remodelling of shop-houses, deftly reconciles the new with the old.

In the case of the National Museum, a large gallery extension is added to the rear and is partially buried into the hillside of Fort Canning. The old building is subjected to careful restorative surgery while the new wing stands apart as a contemporary composition of glass and aluminium and the two are separated by a transverse top lit concourse which frames the historic rear elevation.

In the case of the theatre and concert hall he responds in full to his client’s instruction to: ‘Restore the monument to its former glory and give us state-of-of the art performing venues’. A lost courtyard between the two buildings becomes a glazed atrium space that serves both buildings. A new auditorium, clad in mellow timber is inserted into the theatre and the concert hall is carefully restored to enhance its neo-classical character whilst improving its acoustics.

The Lee Kong Chian Natural History Museum, designed by Mok in 2011, houses the University’s zoological collections. This was conceived as a ‘moss-covered rock’ formed from dark-stained in-situ concrete with one of its sides cut away to create a landscaped cliff. The rock was raised on a landscaped podium that bridged over a service road to connect the Museum to the rest of the centre.

Alongside architects Wong Mun Summ and Richard Hassell of WOHA, Mok clarified his approach to architecture in a joint exhibition that was shown in Berlin in 2006. His half of the exhibition was entitled ‘Chinese More Or Less’ and in it, he expressed his belief that ‘Singapore is essentially a migrant society. While citizens acknowledge Singapore as their political homeland, some cannot help but look to somewhere else – often the land of their ethnic origin – as a cultural homeland.’

He maintains that, after more than half-a-century of nation-building, the idea of multi-culturalism has taken hold, and that he should adopt a multicultural position. He is uncomfortable with labels and avoids being branded by any of the plethora of ‘isms’ that have littered architectural discourse during recent decades. Thus, in the opening paragraphs of his book, he distances himself from the label ‘Tropical’, pointing to its colonialist connotations.

For fifty years, the island republic of Singapore has acted as an experimental laboratory of town planning and architecture, and Mok Wei Wei has been one of its key players for more than thirty of these. This book offers it readers a detailed account of his work as well as providing strangers to Singapore with a useful introduction to the architecture of the city state. Clear and succinct descriptions of key buildings are illustrated with explicit, well-annotated drawings and a judicious mixture of large images and useful snapshots. These are accompanied by a comprehensive catalogue raisonné and a number of supporting essays.

*David Robson has had a long association with Sri Lanka, having taught in the Colombo School of Architecture during the early 1970s and worked as an adviser on the Hundred Thousand Houses programme in the 1980s. He has also written a number of books on Sri Lankan architecture including a monograph on Geoffrey Bawa. He first encountered the work of Mok Wei Wei in 2005 when he was a visiting professor in the National University of Singapore.

Mok Wei Wei, an admirer of the work of Geoffrey Bawa, has delivered one of the annual Geoffrey Bawa memorial lectures in Colombo and has served as a judge for the Geoffrey Bawa Award for Architecture.

Book facts:

‘Mok Wei Wei: Works by

W Architects’

Thames and Hudson, London, 2020